Sérendipité

By invitation from Réseau documents d’artistes, art critic and exhibition curator Émilie Flory visits various regional archives. In her exploration, she draws a map of works dealing with landscape, while offering a glimpse of the process of creating a presently imaginary exhibition.

In the beginning are reproductions and text, then getting closer to the artists, to ideas and fiction, and finally connecting thoughts, forms, common interests. Dig in, pick and choose, read, browse at will and let it rest. I’ve chosen this protocol, which is not so far-removed from the workshop of potential exhibitions created for Frac Aquitaine some ten years ago. Thank you, Georges.1 Let’s go!

I know what I know and am pleased with what I don’t know. My mind is prepared. Serendipity is

a disposition to find what you’re not looking for. One might happily consider a part of the work of the curator or art critic in this way. With the same care, observing and reading completed works, works in progress, and the scars of making that remain on work tables and walls. Listening to the artists. A word, a color, a gesture, a flash and emotions ensue. I love folks with hesitations, attuned to every vacillation of their heart…2

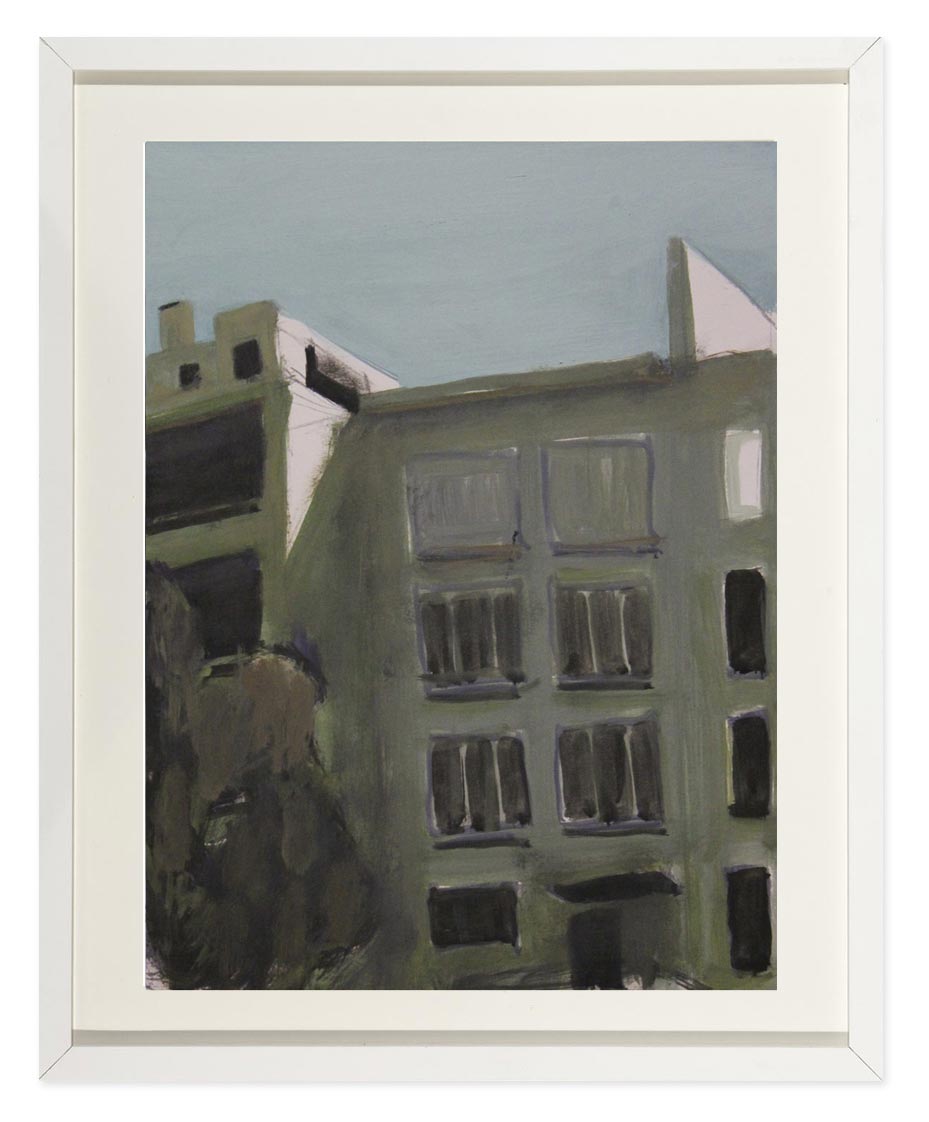

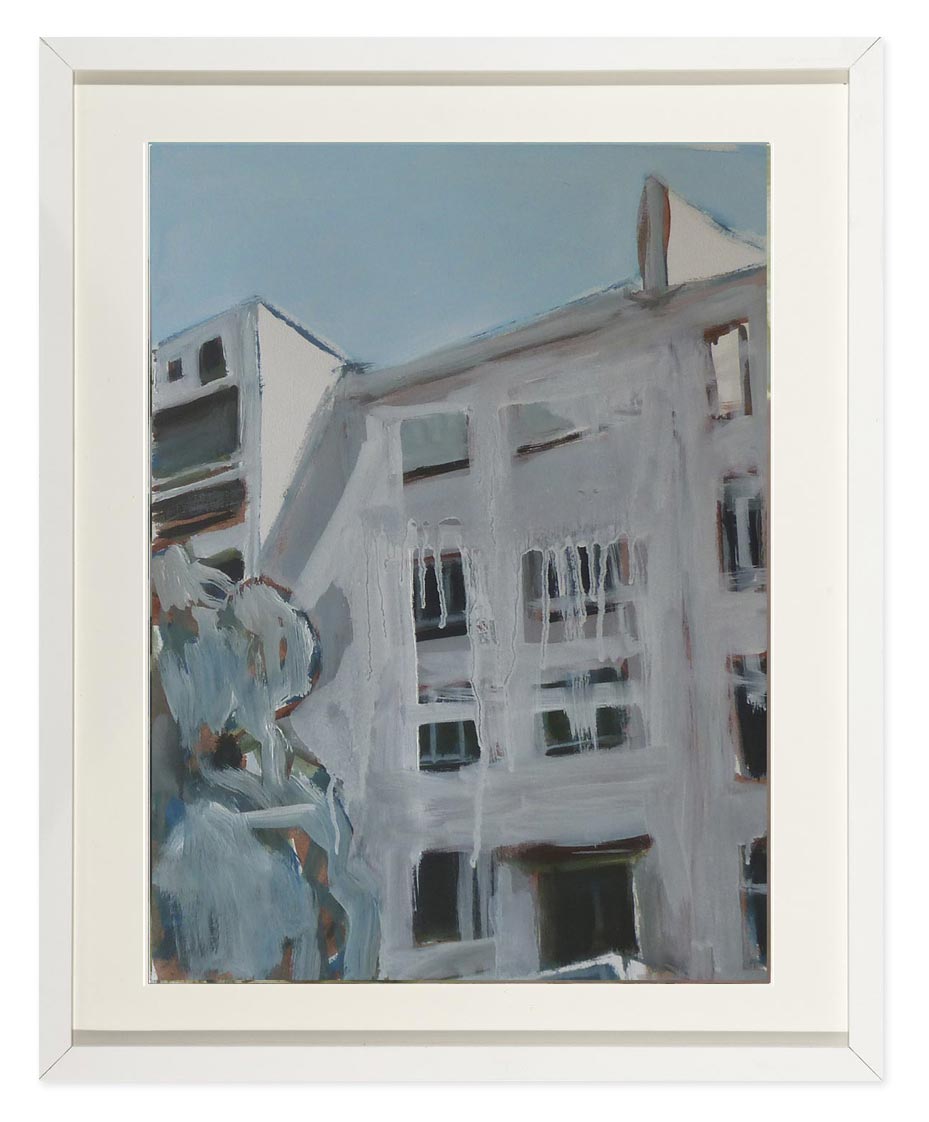

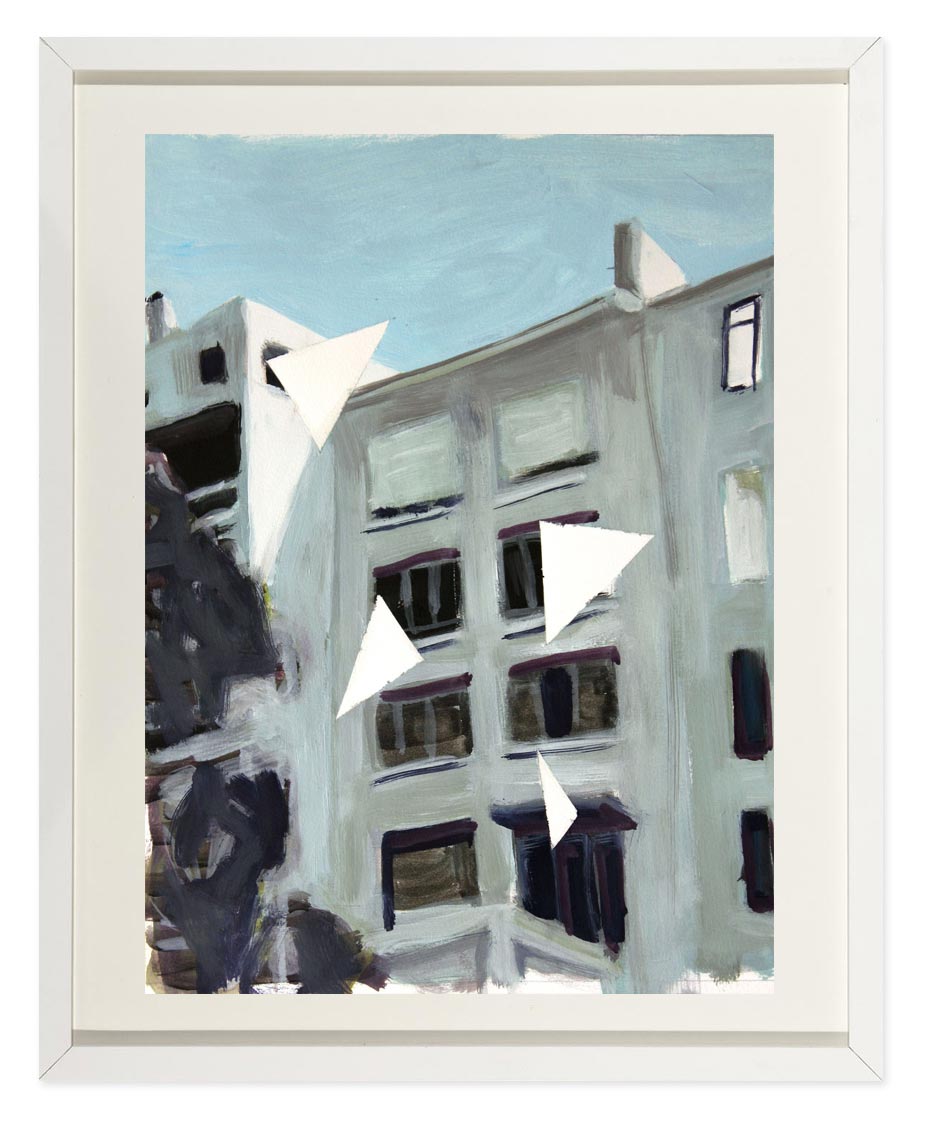

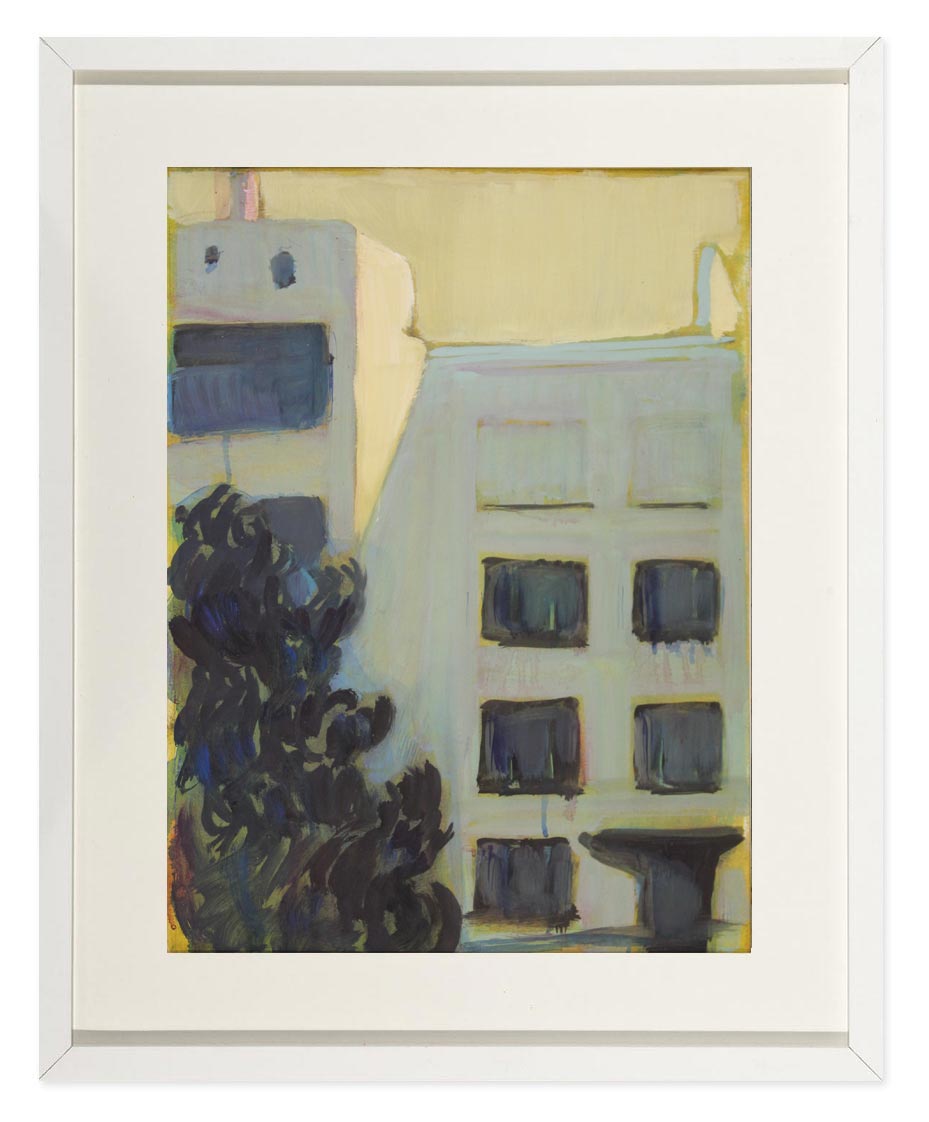

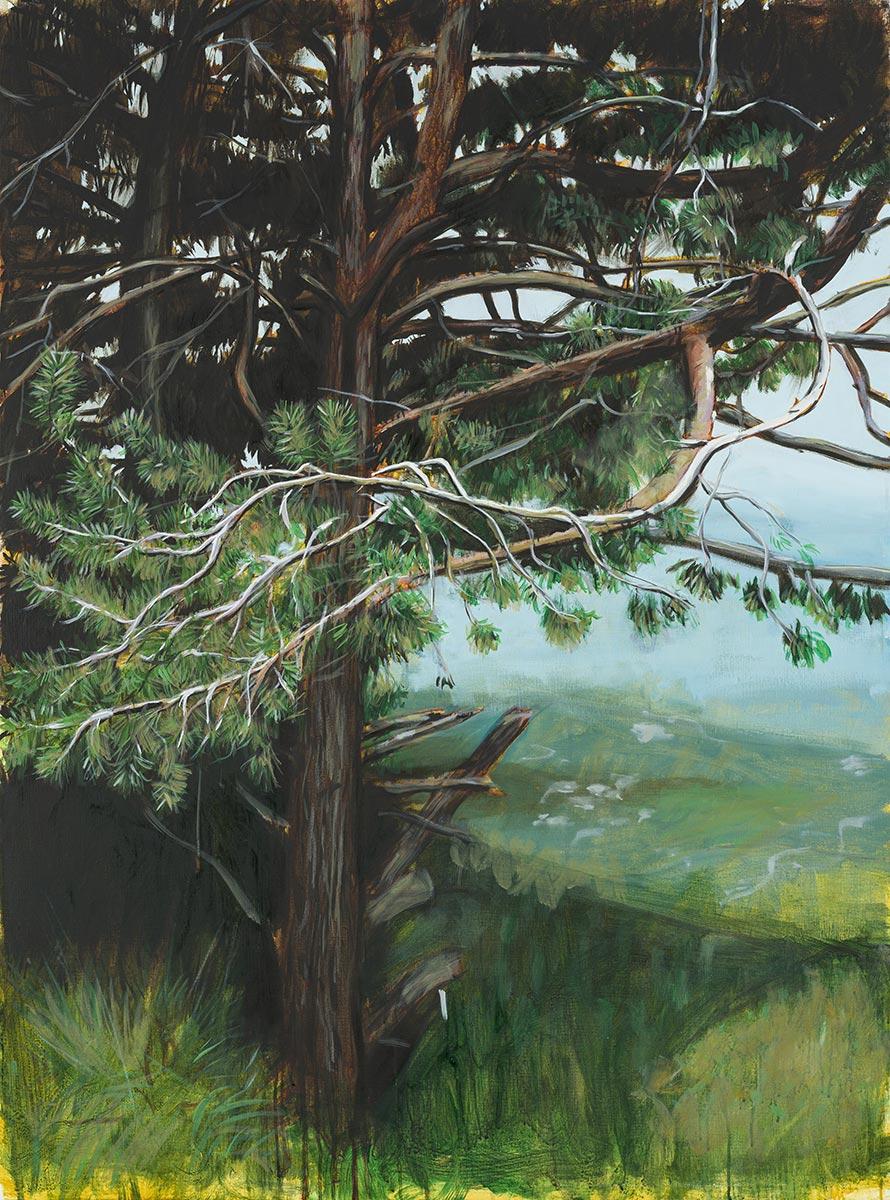

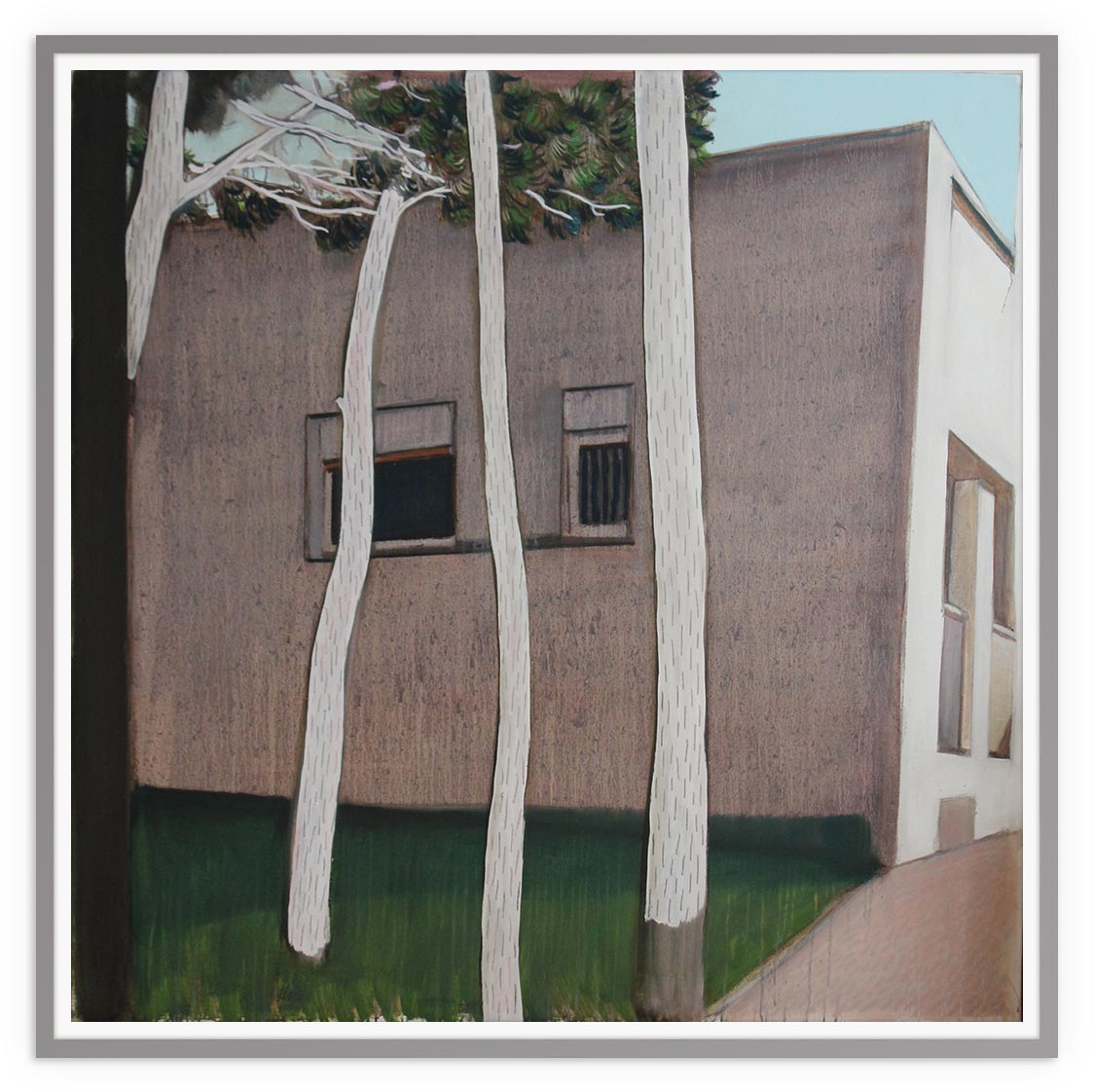

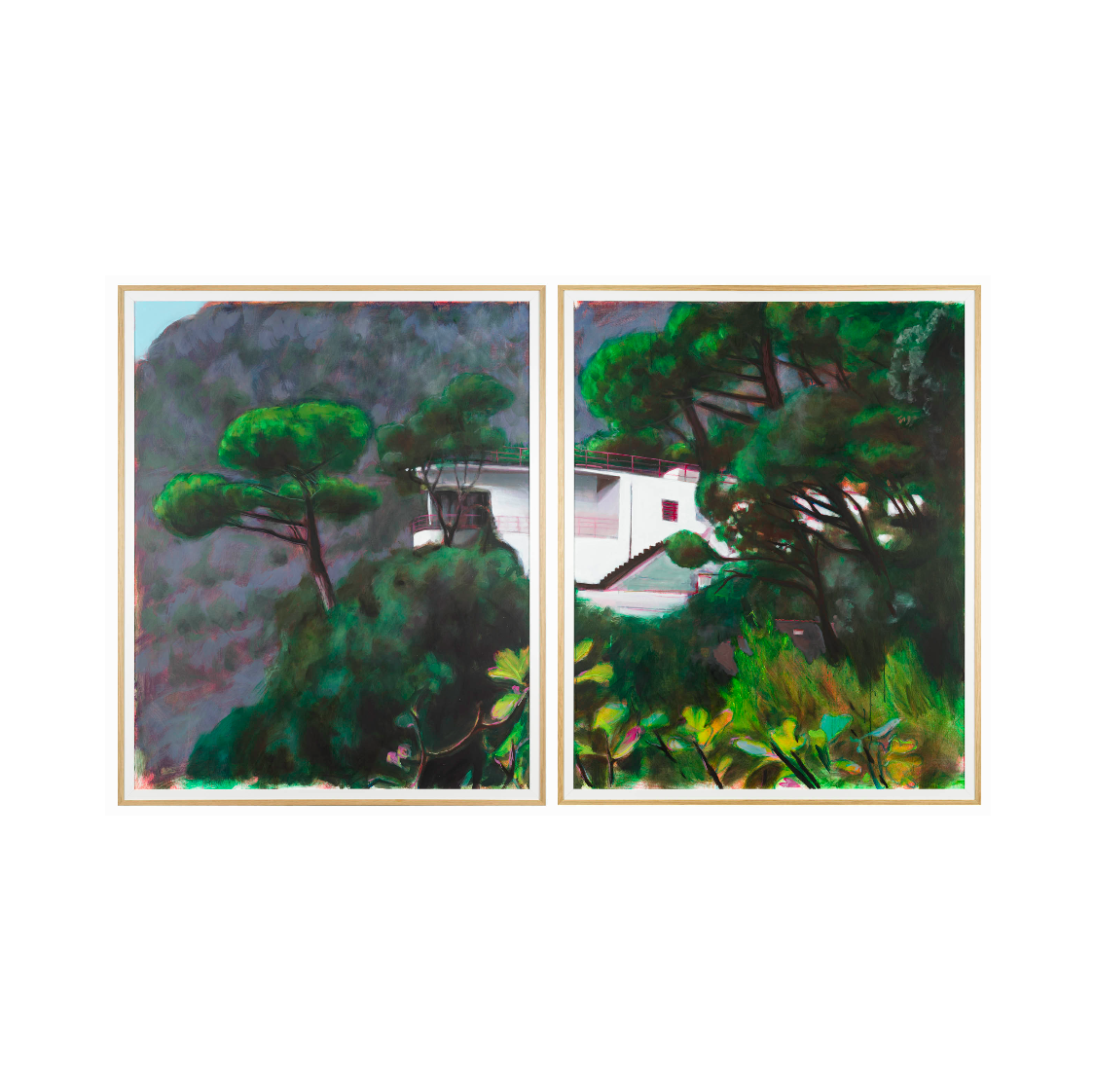

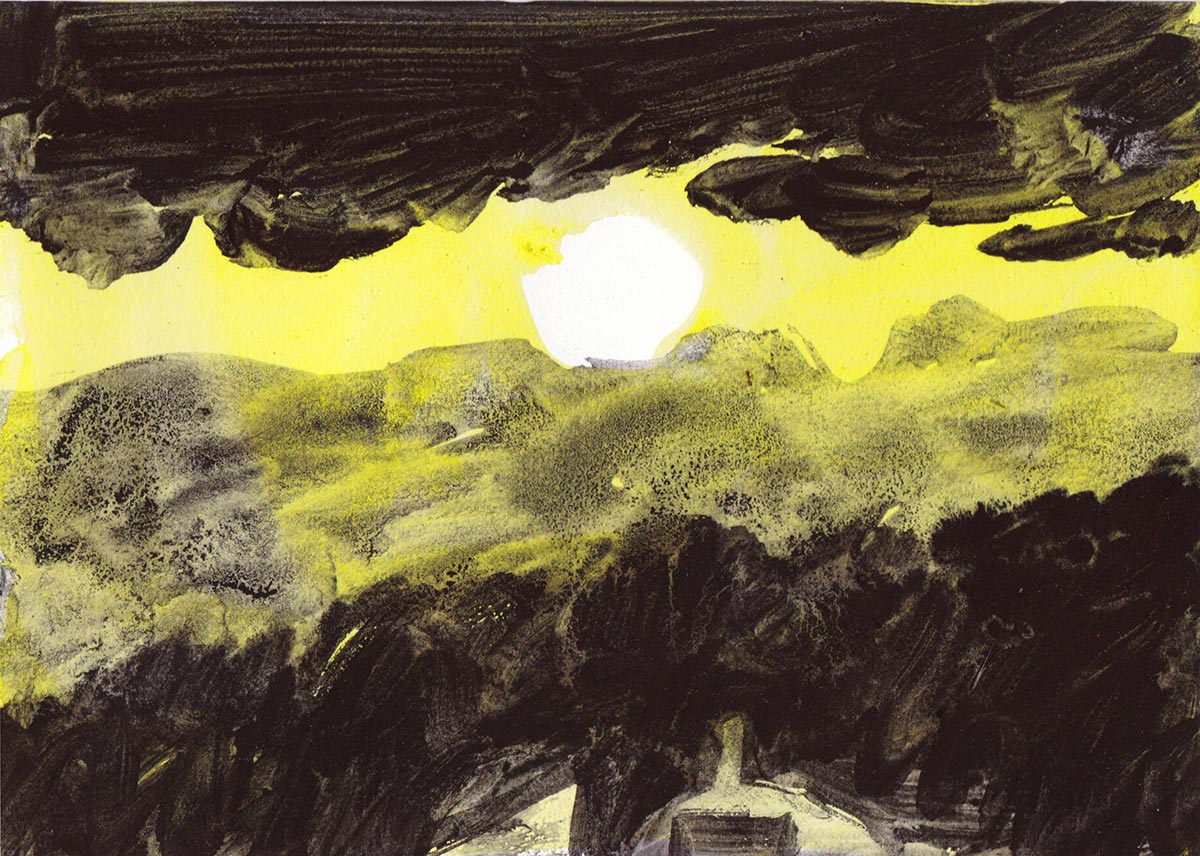

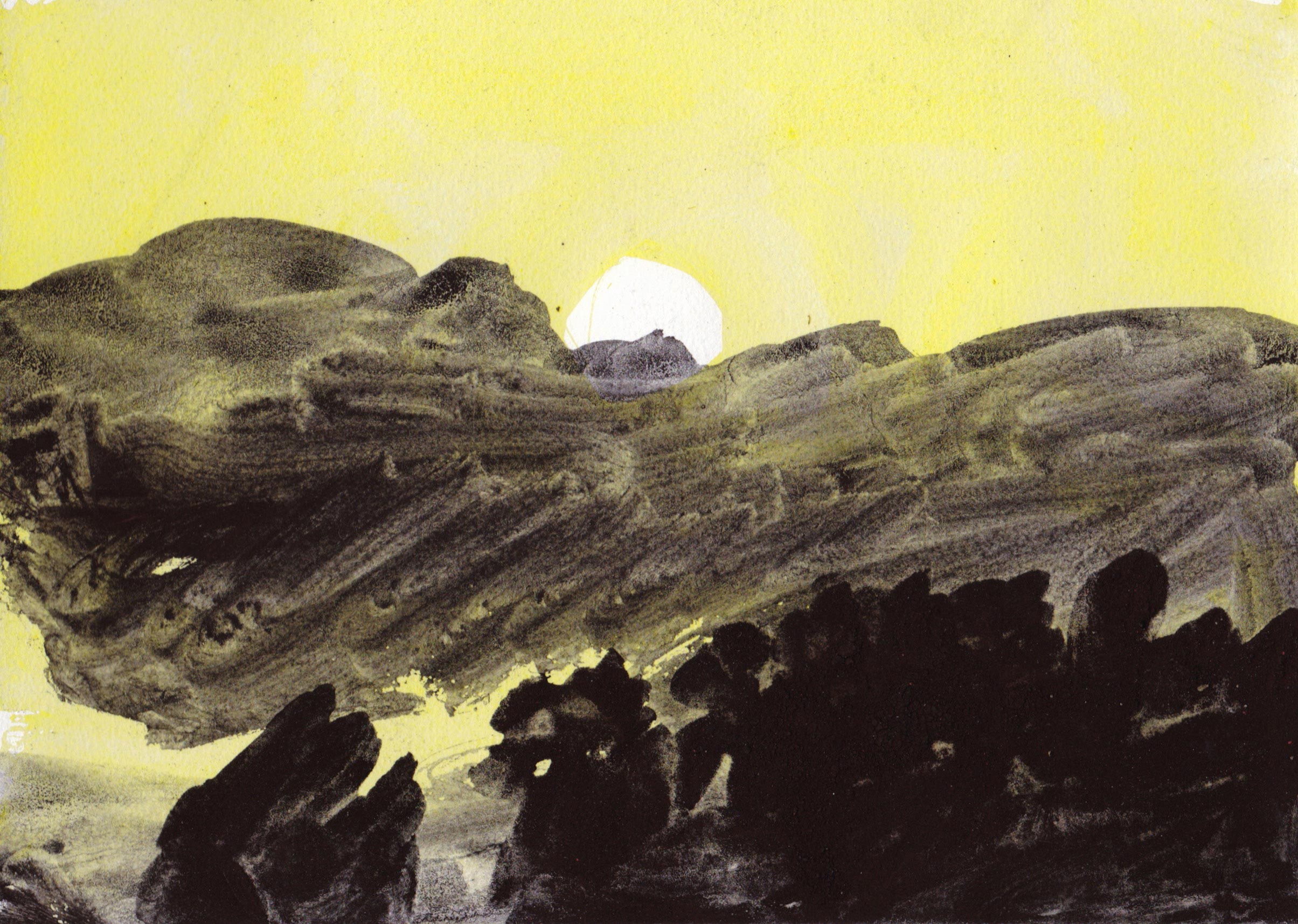

The imagined exhibition begins with Jérémy Liron. I was pleased to discover Tentative d’épuisement [Attempting exhaustion]—just as I’d been thinking of Perec3—, somewhat removed from the lone tree with its twisted branch, which I’d first seen connected to Jean-Claude Ruggirello’s Jardin égaré [Disoriented garden], but less removed from my desires for contemplation; I’ll leave the uprooted, blossoming cherry tree and the disabled pine here, and turn to the twenty-nine oil paintings on paper.4 The series displays an anonymous, ordinary housing unit whose concrete skin starts to liquify. Slowly the browns from the rectangle of the windows melt into the blue gray facade, white triangles formed by rays of the bright, midday sun multiply like a disco ball on the surface of the paper. The angle changes slightly, very slightly. The geometric figures take the viewer out of the image and invite abstraction, an energy.

Under the pale blue sky, yellow in the morning, rosy in the evening (if it’s not the other way around), the bars of the windows are vanishing; the truth of the architecture remains, melancholy of days, music of light. I know these facades. They’re everywhere. They’re in the Var region of my childhood, not far from the upright trunks that punctuate urban boulevards, drawing black lines with their shadows on the low walls of nameless streets.

Once we consider the work as a whole, it’s clear that the landscapes5 are suggestions for walks, invitations to roam the streets, to contemplate what makes an image. Through a precise framing of details, a tree opposite the sea, renowned or vernacular architecture, or a view through the window, the artist brings the viewer into a story, a film to recreate. What’s out of frame is easily imagined: the rest of the path, roadside flowers, sounds, the curves of the opposite building’s balcony…Painting allows for fanciful perspectives and a world whose skies are cloudless, even when they’re “low, heavy” and “press like a lid”,6 a world in which the impossible twist of a branch surprises no one.

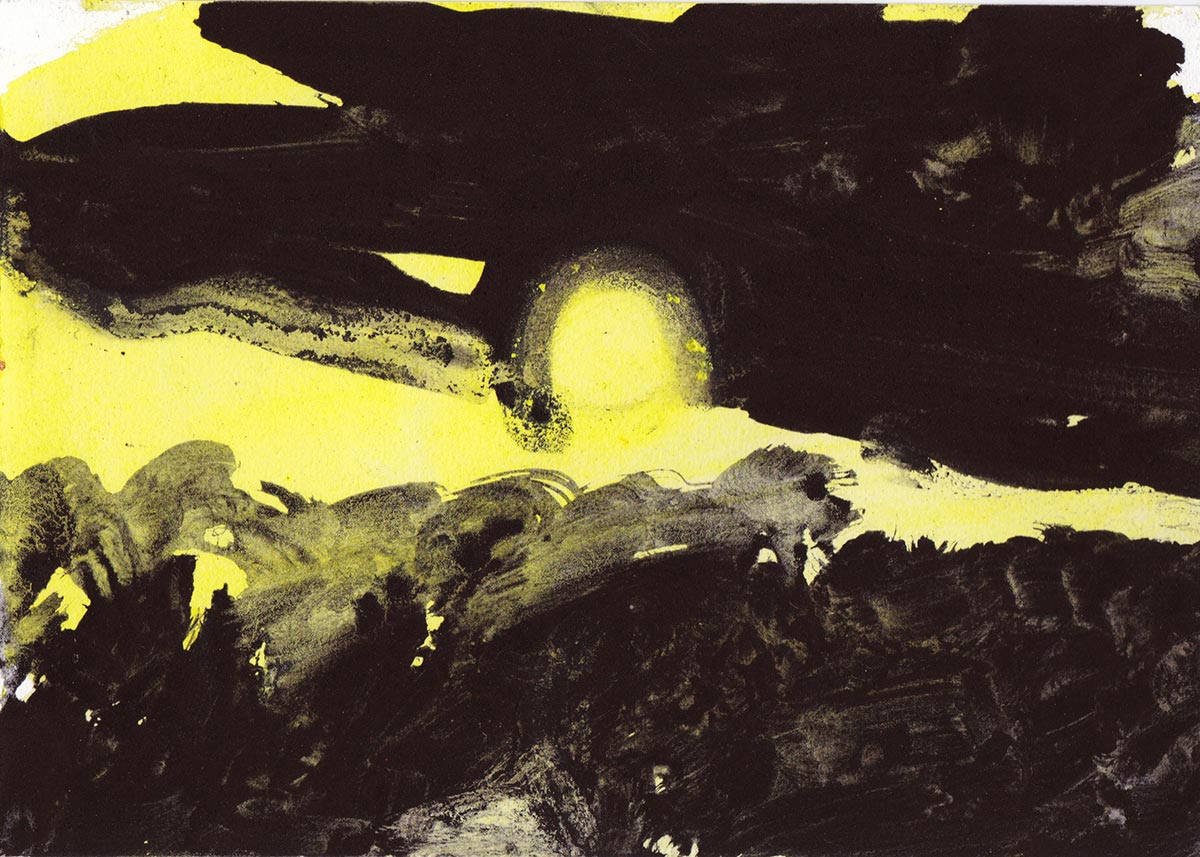

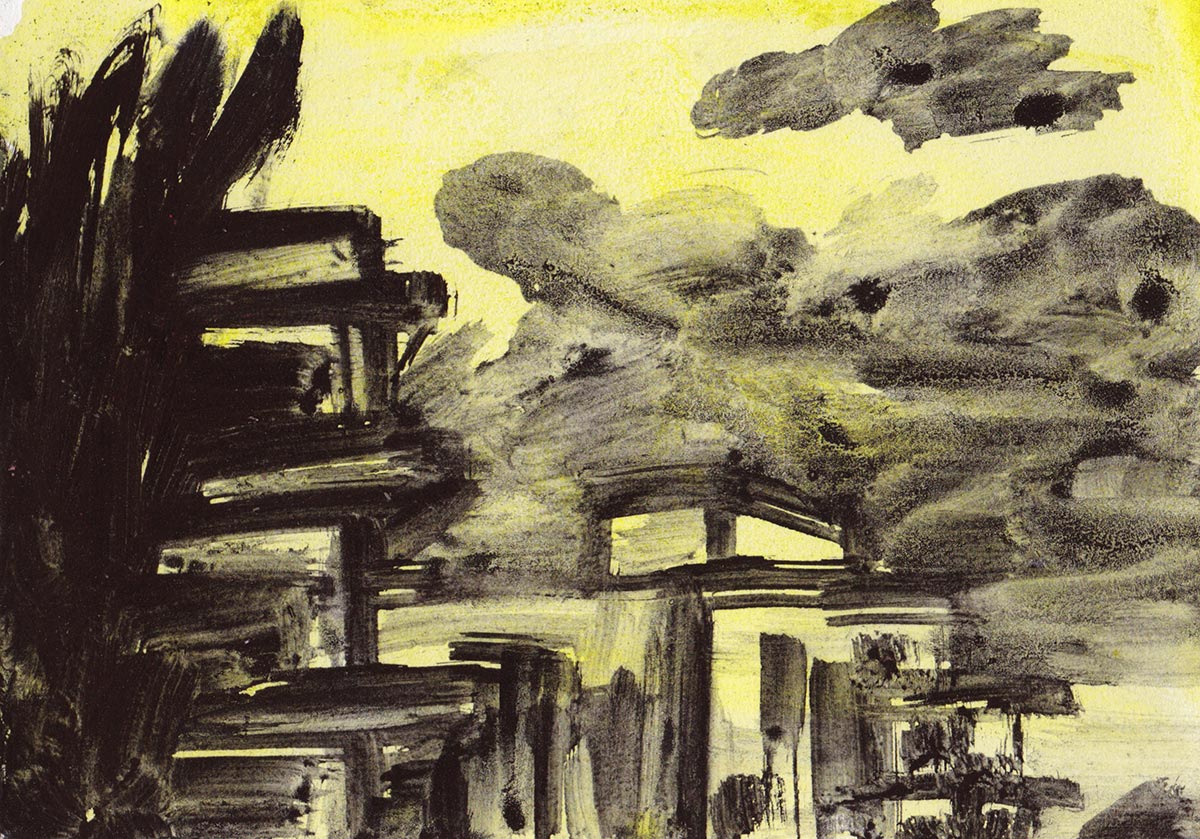

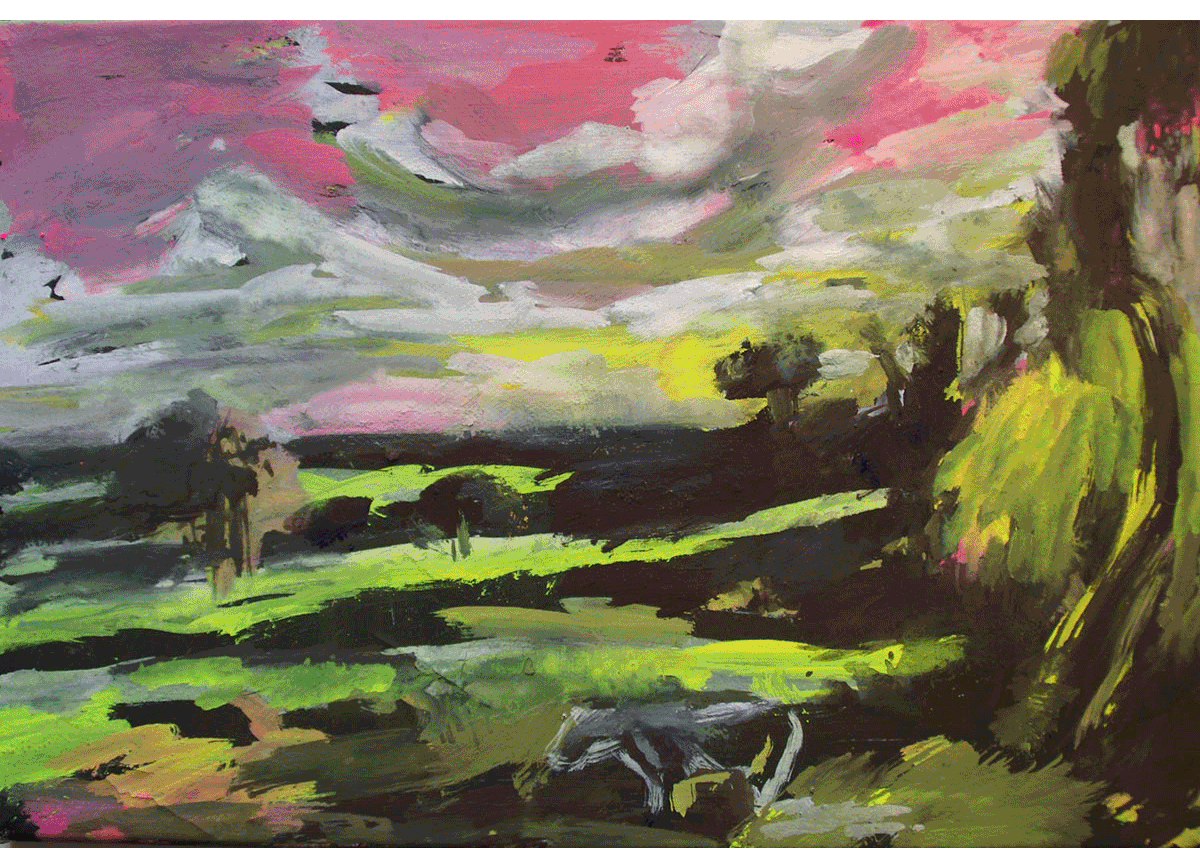

Roaming and movement is seen in recent paintings by Florence Louise Petetin, with a clear relationship to photography linking the artists’ work. But while Liron often chooses formats that are identical, square and placed under plexiglas to enhance the gloss and a certain detachment, Petetin paints on anything she can. She’s even disassembled furniture for a medium. She uses ancient techniques like egg tempera, bringing an intimacy to her subjects, which she sometimes “pimps up” with fluorescent powders. A series in-progress, Untitled, on wood in small, portrait formats, shows paths across hours of the declining day, when light and reflections trace abstract shapes, imbuing the rural and suburban spaces with a divine aura.

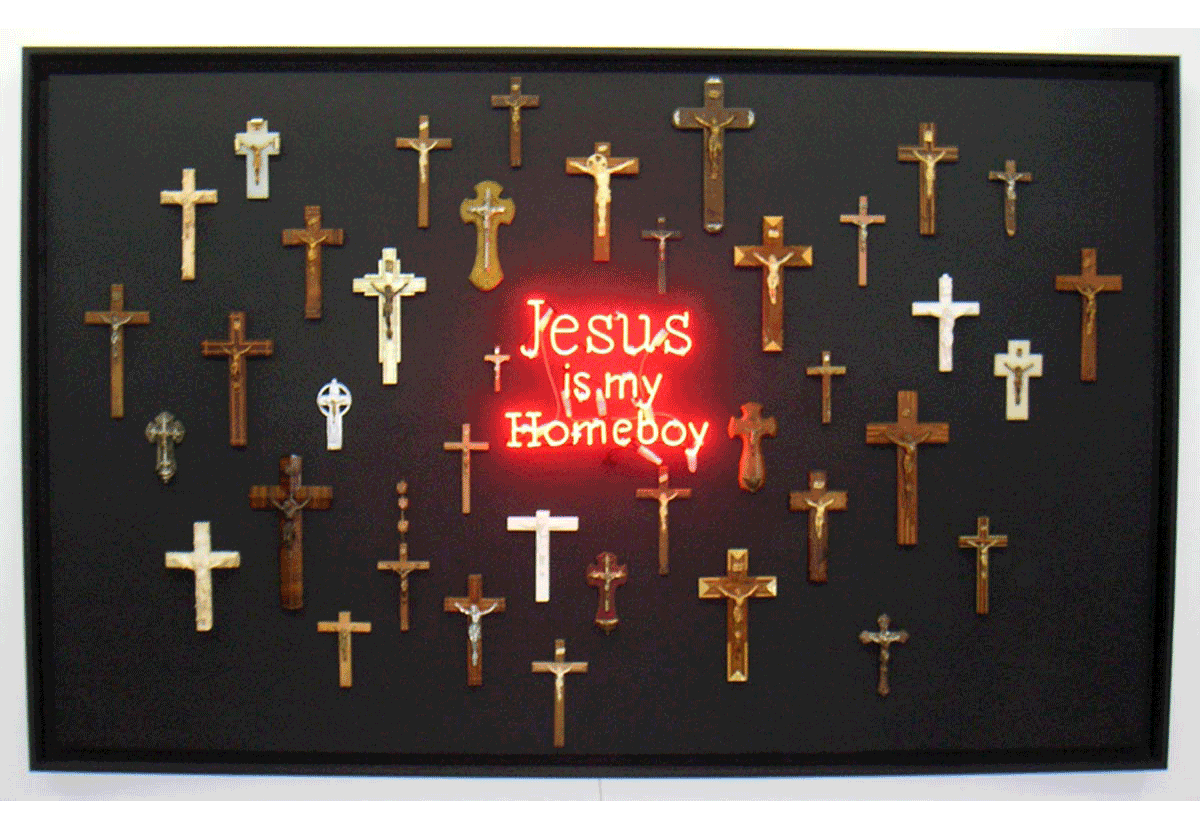

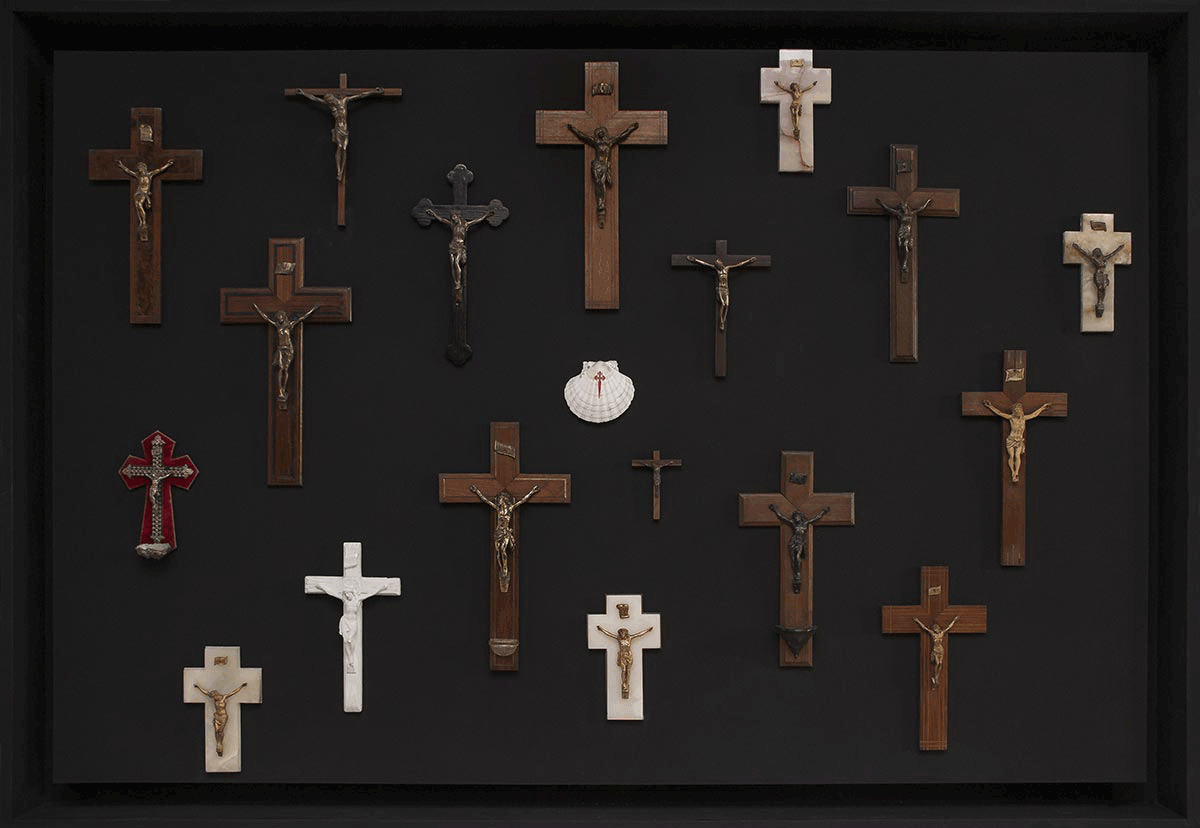

Paths and the divine also meet in the large-scale works of Lionel Scoccimaro: Jesus is My Home Boy, Santiago Memories, and Santiago Memories (Black Version). The sculptor, whose work is based on amateur art practices and low culture, sets crucifixes in a large black frame, surrounding a pilgrim’s scallop shell. Reference is enough to generate the icon. Here, quantity and repetition of the motif, as in Liron, reinforces the power of the objects to make up an image: the universal symbol of Christian faith across the world. The crosses were collected by the artist along the road to Santiago de Compostela. Pilgrimage is a tough challenge for body and mind. A voyage on foot through all types of weather with a specific purpose is a way of breaking from the world to return to the earth and landscape.

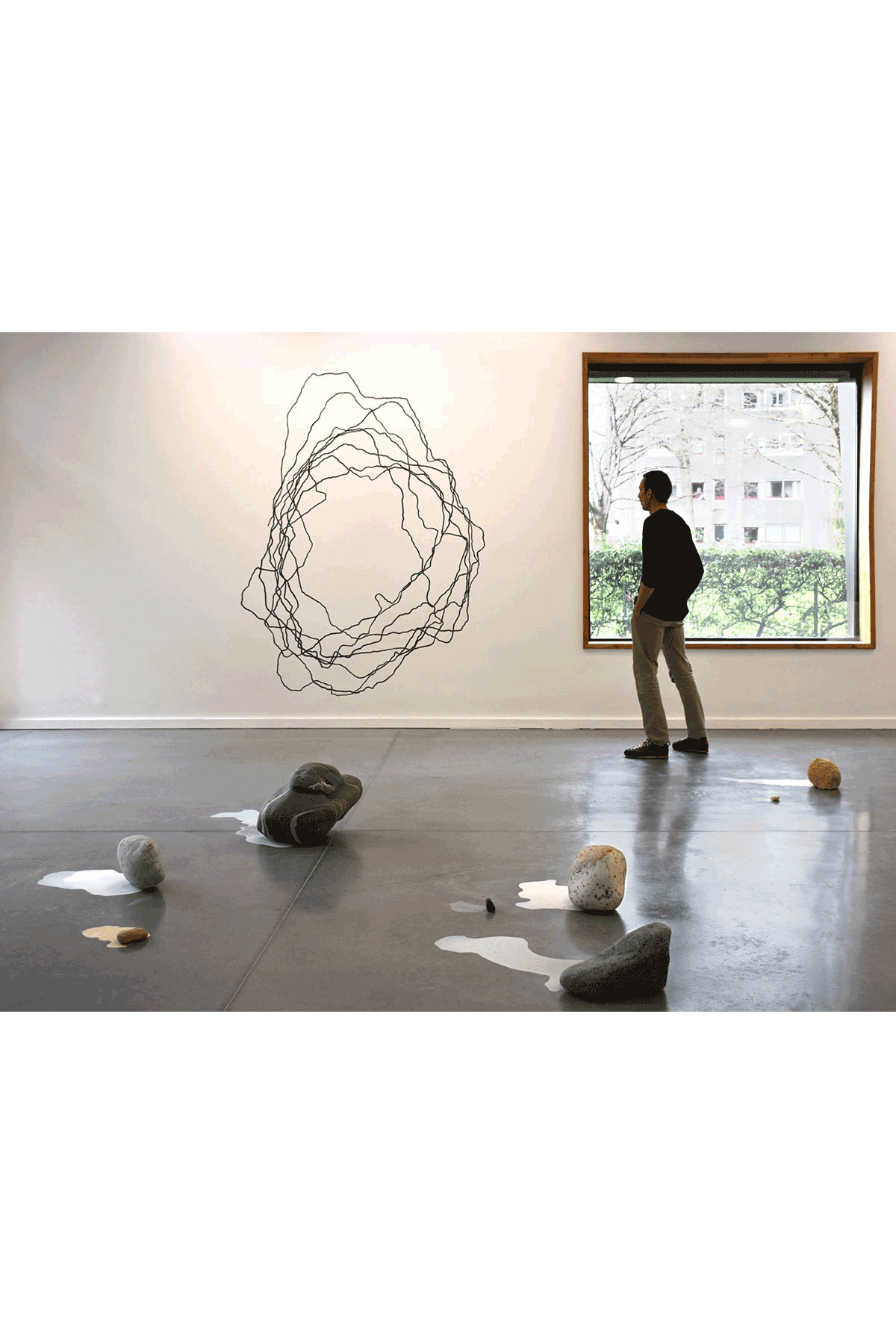

In an exhibition, you need works that tie things together. Here it will be Adrien Vescovi’s installations, starting on the floor, as in his exhibition Slow Down Abstractions, then descending from the ceiling, as in the series Land. Some items can be displayed outdoors. Indoors, the works transform into an accessible space, a cave conducive to dreaming, a return to the material, the mineral. Back and forth from exterior to interior, the artist invites us to walk and feel, not too different from Homo sapiens, or Santiago pilgrims.

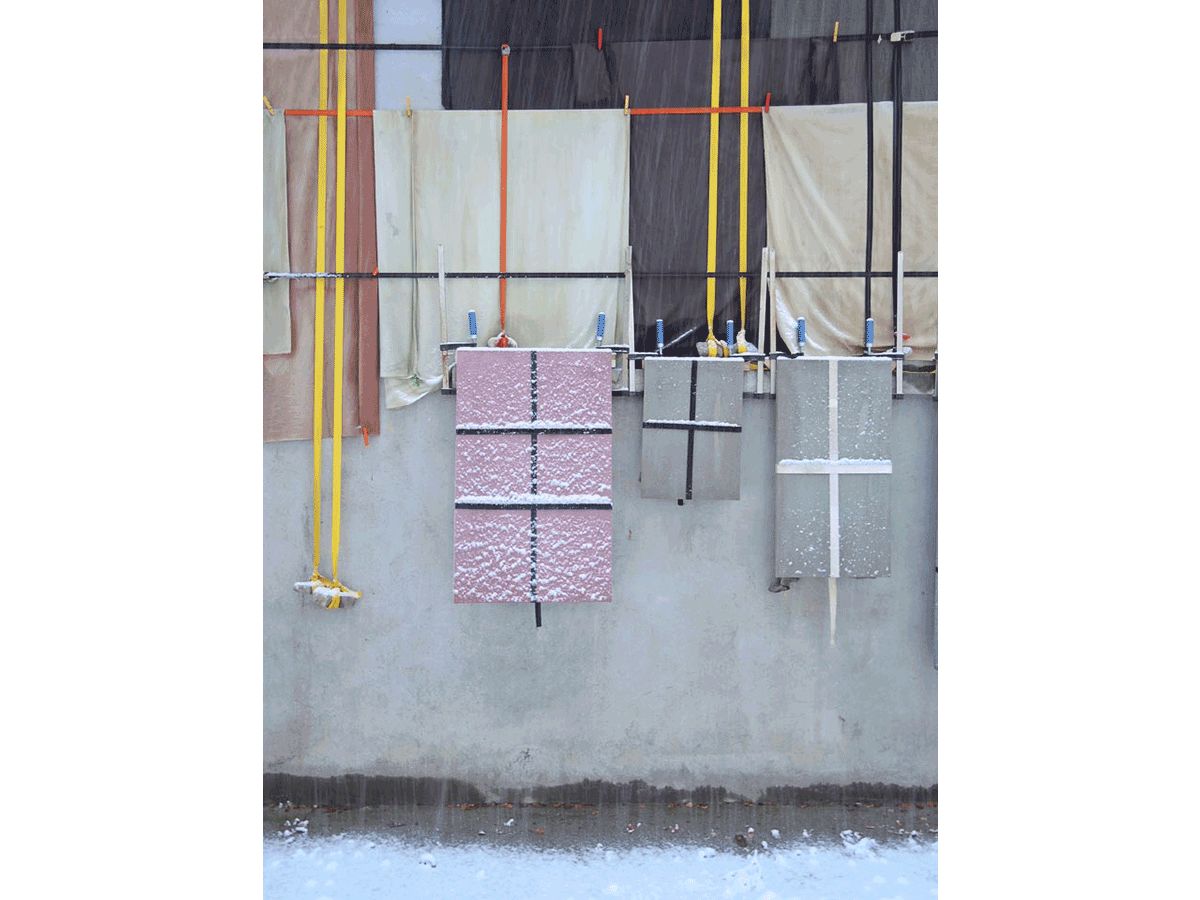

Vescovi’s work is immersive, and here, emotions from childhood are evoked once again: making cabins out of cloth, mixing plants from the garden, feeling sheets under bare feet. Vescovi collects natural pigments, like ochre from Roussillon or soil from Morocco, foliage and plants gleaned from the mountains of his youth, now from the environments of places that host him. He makes infusions and decoctions into which the textile is plunged and boiled to extract all the color. With linen sheets and old cotton, the media he chooses have histories, they evoke poetry and melancholy when they assume elaborate designs, knotwork or embroidered monograms with forgotten references. In the studio, the artist leaves the textiles that will be canvases in the wind and snow. He waits for natural changes induced by the elements, sun burn as much as frost, so that colors emerge without his being able to predict precisely what his preparations will do to the fibers. Jars of yellow and brown liquids will give the unbleached weave surprising mauve tones, or bright oranges, who knows.

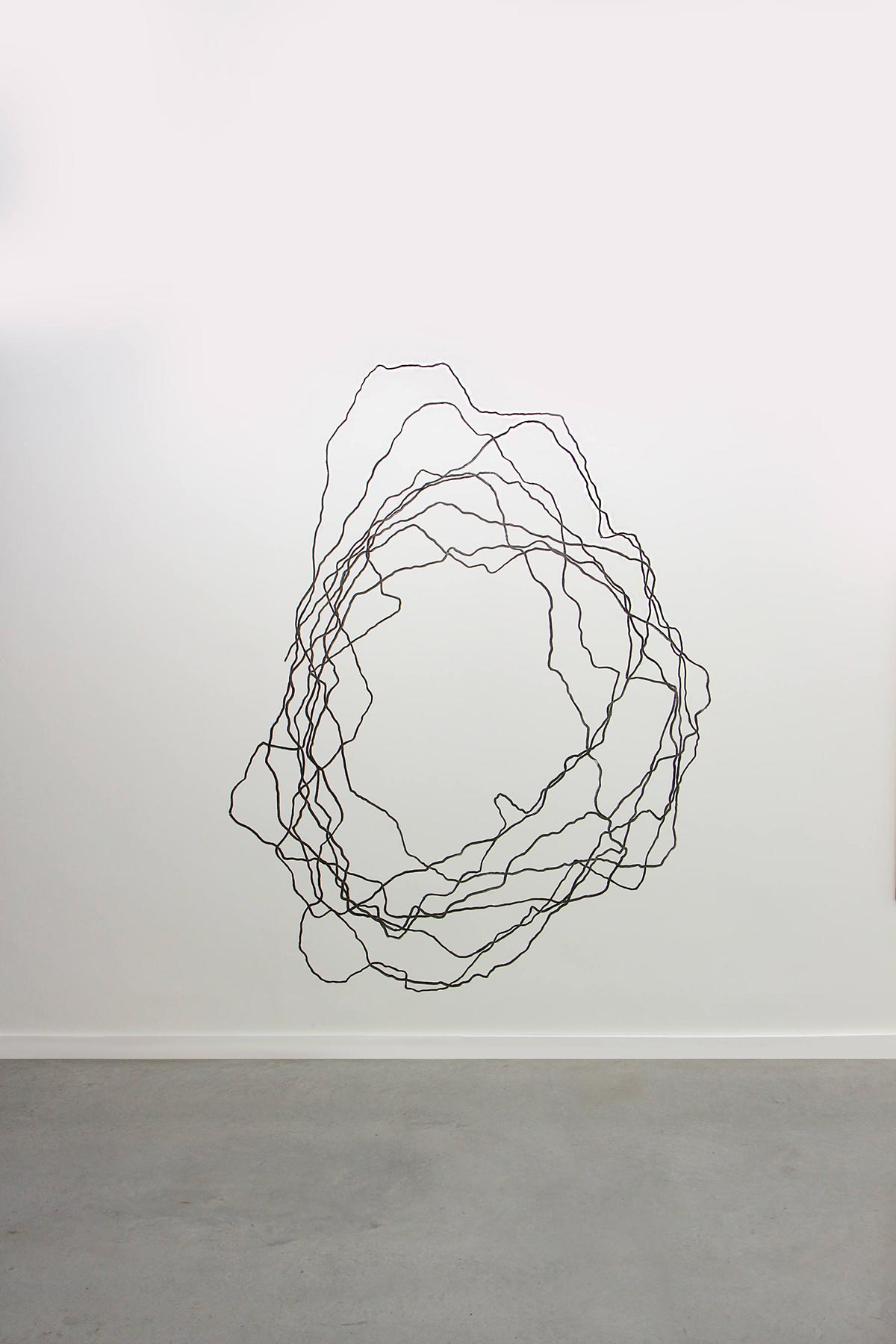

This labor, often invisible to the viewer, is what stands out: time spent collecting the elements and preparing the dye baths, drawing, assembling, adjusting and sewing the strips to create a new landscape. The artist’s body is present despite its absence, as in the work of Christophe Clottes. This artist roams mountain paths, removes rocks and extracts pigment powder used for specific purposes: drawing on walls, making puddles or digging furrows. Here I also locate a relationship between interior and exterior. Both artists draw elements from nature that will be part of the exhibition to speak to the complex relationship humans have with natural elements.7 Walking comes up again; the type that’s connected to the world. Échos is a set of drawings produced on trails in the Pyrenees and the Lot river gorges. Without looking, the artist follows his subject visually, his hand armed with a marker. He focuses on the form of what he’s looking at and what separates it from its surroundings, point by point. He repeats the operation three times, and changes of attention, distortions and echoes appear. Next to it a masterful drawing on the wall is imagined using the Écho erratique protocol. Its vibrations resonate with the lines formed not far off by Vescovi’s Cahier d’Alchimie de Vescovi.

On certain nights in the large room eased by fabric, Clottes will hold a concert in which pebbles from the Gave de Pau river sing. Other nights we’ll hear Stick or Stone by Félicia Atkinson. In addition to complementary musical work, the two artists have a vast field of references and interests in common. As offspring of Fluxus, they both refuse to restrict their art to a particular medium or practice.8 There are also correlations in their investigation of rocks and living things—in Australia and the American West for Atkinson, in Basque Country for Clottes. The sound works, a touch too mystical for people who are particular, lead to the still silent film, Miel de géant, by Chloé Robert. It’s a perspective on a place. The texture of the image recalls the past, with aerial views of “her” island: Reunion. Volcanoes and all that these landscape convey of myth and history become the terrain of a giant, in a playful, atemporal journey. Discussing a work in progress is always tricky, but like it is in the workshop, here and now, I appreciate its fragility and the simple emotion it expresses in its current state.

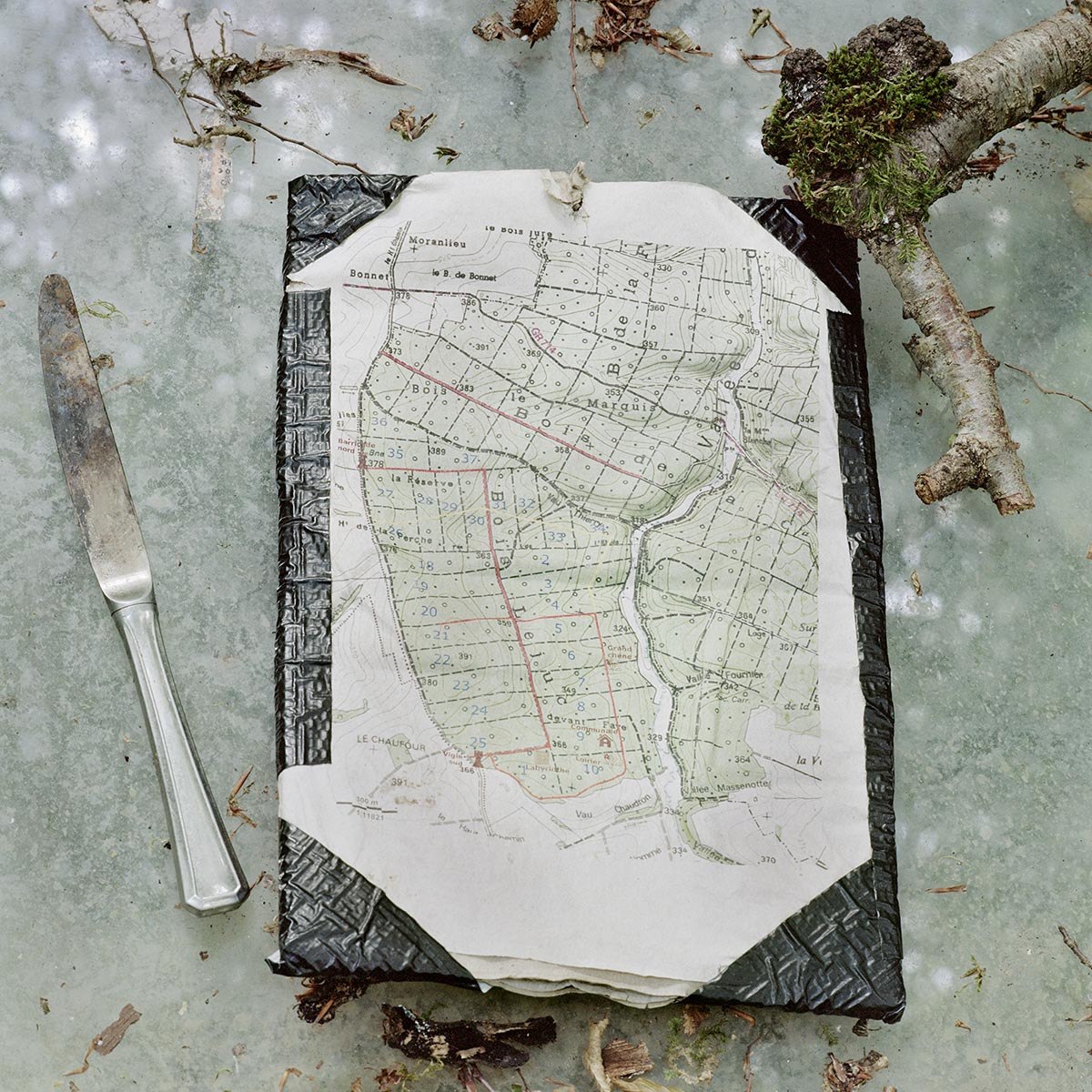

Exhausting a place by walking, going down its paths, following maps and topographies is another way of thinking about the landscape and nature. In the series Les heures bleues, Fernanda Sánchez-Paredes travels the roads in the early morning. She frames wide open spaces and woods with her camera, focusing on village entrances, plow furrows and dirt bike trails on riverbanks before everyday life wakes up, before noise and rage arise.

On a big white wall a piece of colorful embroidery stands alone: Bikini by Esther Hoareau. Time stands still, shortness of breath, the eye lingers on the mushroom cloud…rage rumbles.

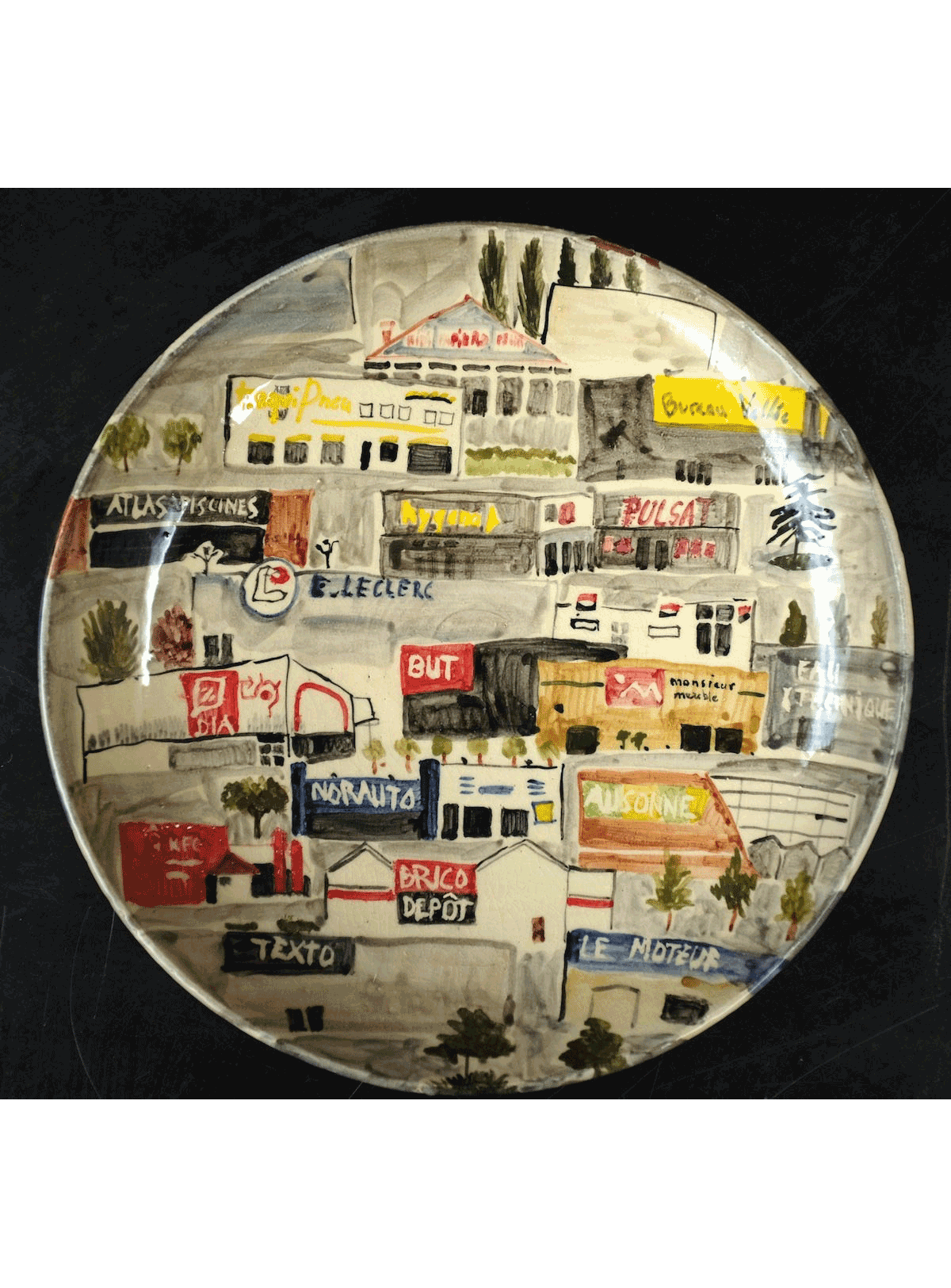

Looking at the series of vases, ACAB,9 by Suzanne Husky, the space becomes political, a scene of struggle and revolt. Arranged on stands at the height of a human being, the pottery that the artist forms from selected types of earth show floral decorations surrounding scenes of protest, citizen combats and demonstrations. On the wall, the photographic series Bure, ou la vie dans les bois [Bure, or a life in the woods] by Jürgen Nefzger, is presented on a three-line grid. For two and a half years, the artist followed activists occupying Lejuc woods in Bure, department of Meuse, trying to prevent the future catastrophe of a nuclear waste disposal site.10 The full text of Thoreau’s Civil Disobedience,11 presented in several frames, punctuates portraits and places, pointing to everyone’s implication here and now. The same goes for video performances by Yohan Quëland de Saint-Pern whose work is also political. He deals with the smalll, confined space of an island, inexplicable, inexcusable police violence against those defending their rights and fight for their land. In much of his work, bodies are active, the body of the viewer with workable pieces or his own body put to the test, as in his 5 filmed performances, Désert [desert], also political. As it is with Jean Bonichon, who likes slopes and putting himself in absurd situations to better reveal the tragedy of the world. These two artists’ performances, which are often long and physically exhausting, are acts of resistance.

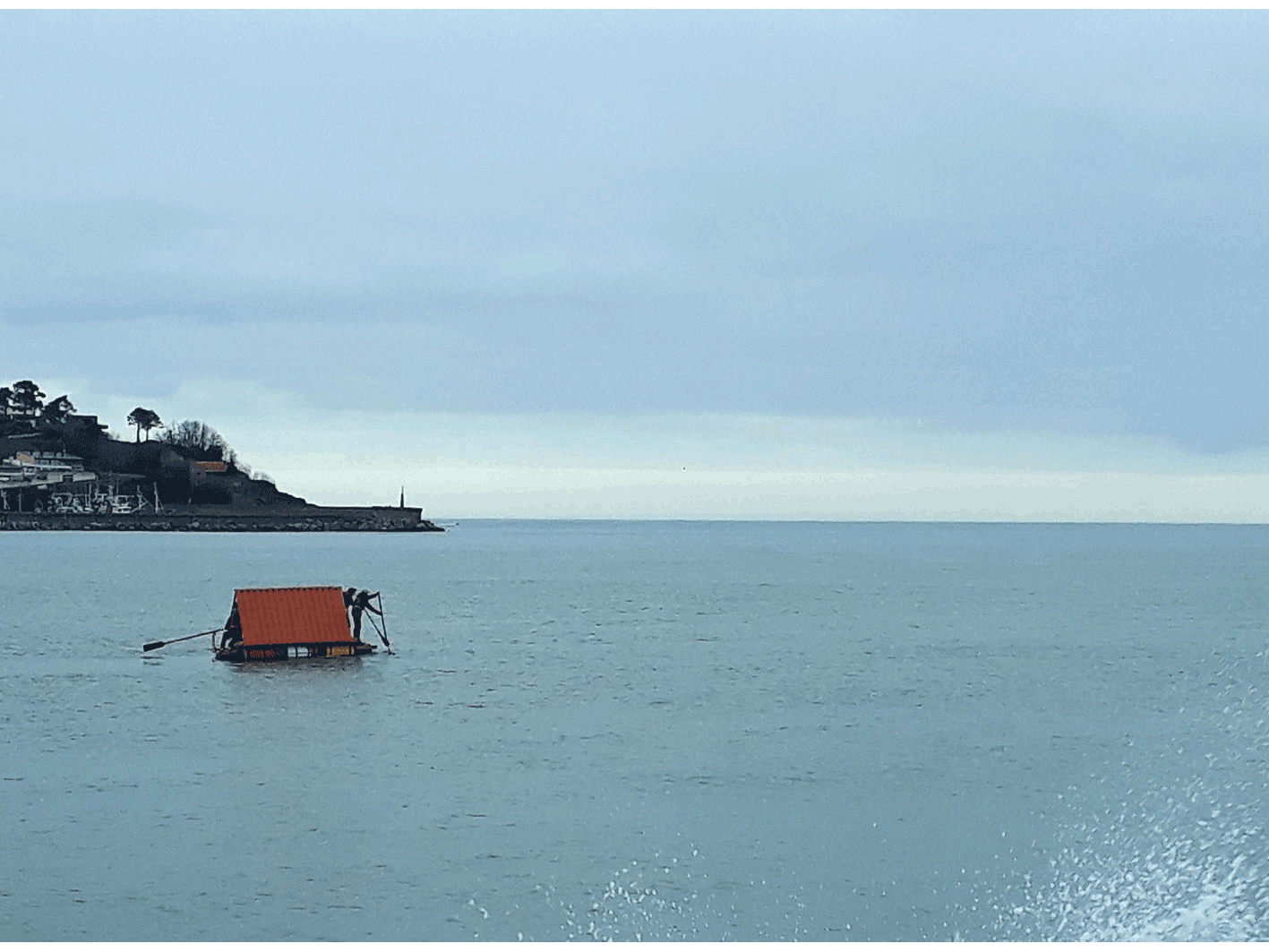

Boga Boga ends the exhibition. Filmed and photographed, this documentation of Bonichon’s performance is quite fertile. In it, a roof-raft on top of barrels descends a river to meet the ocean. It’s three hours of struggling to reach the open sea. The work is a tribute to those who set sail, run aground, leave their lives and put themselves in danger for the dream of happiness elsewhere. The end.

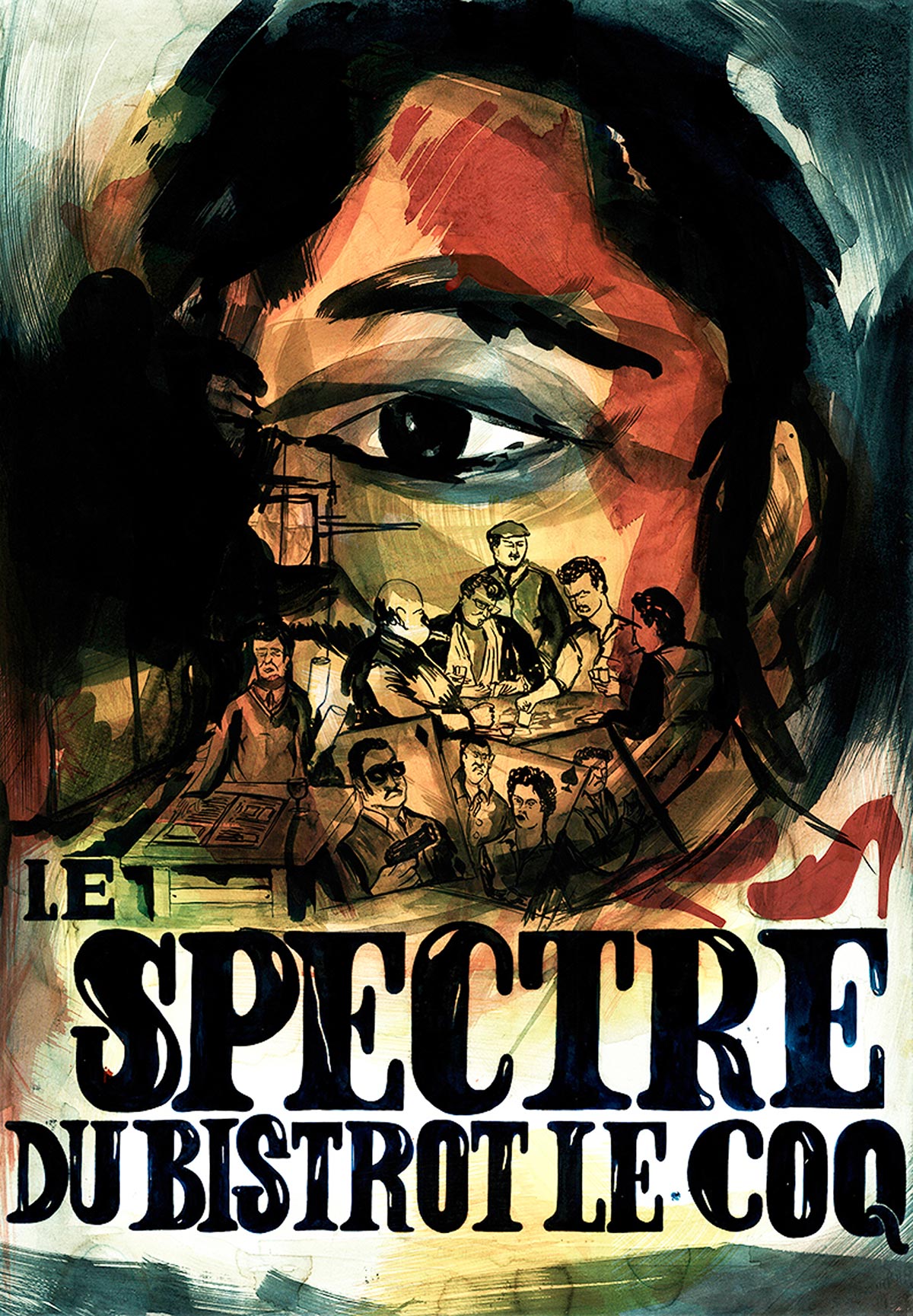

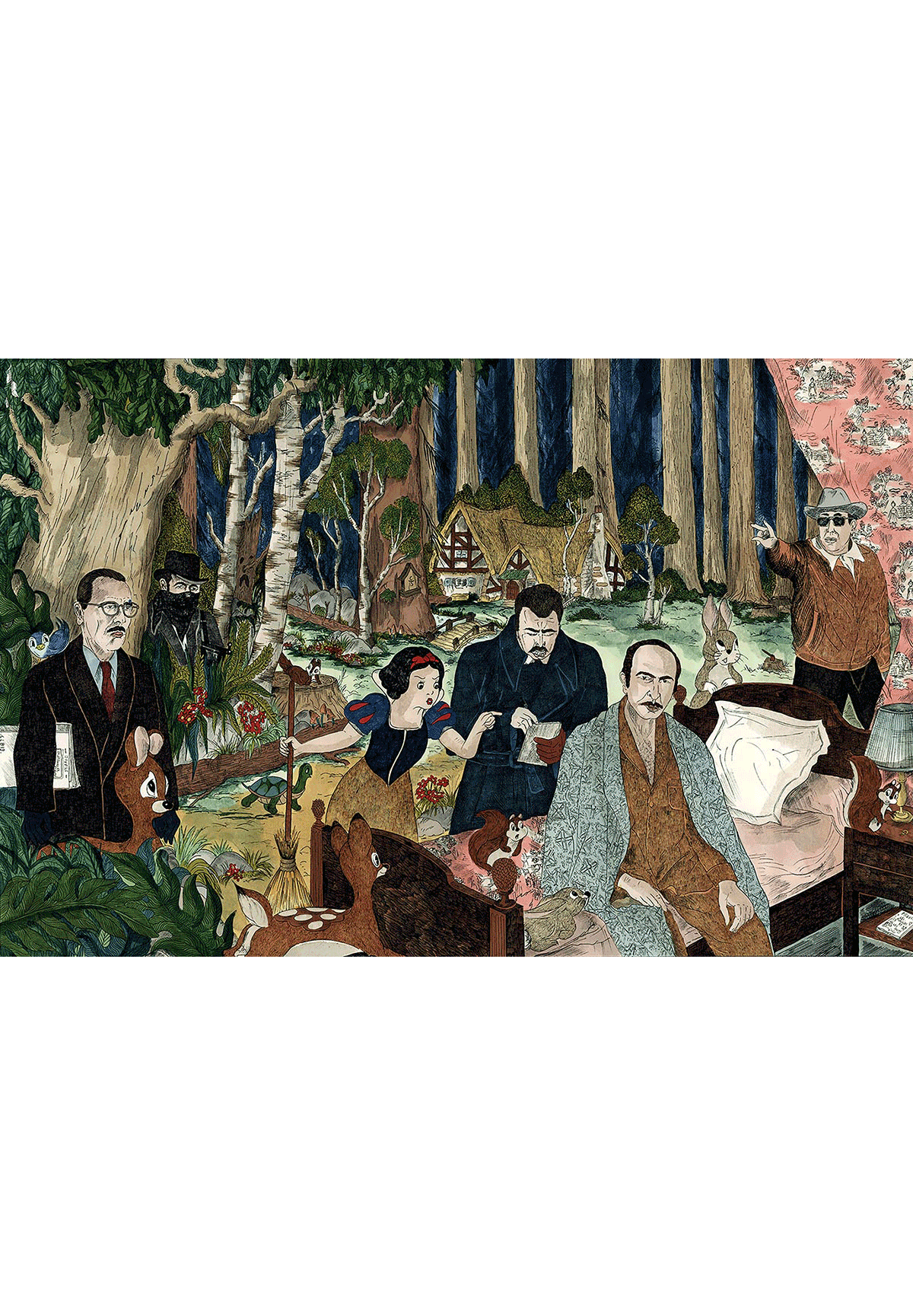

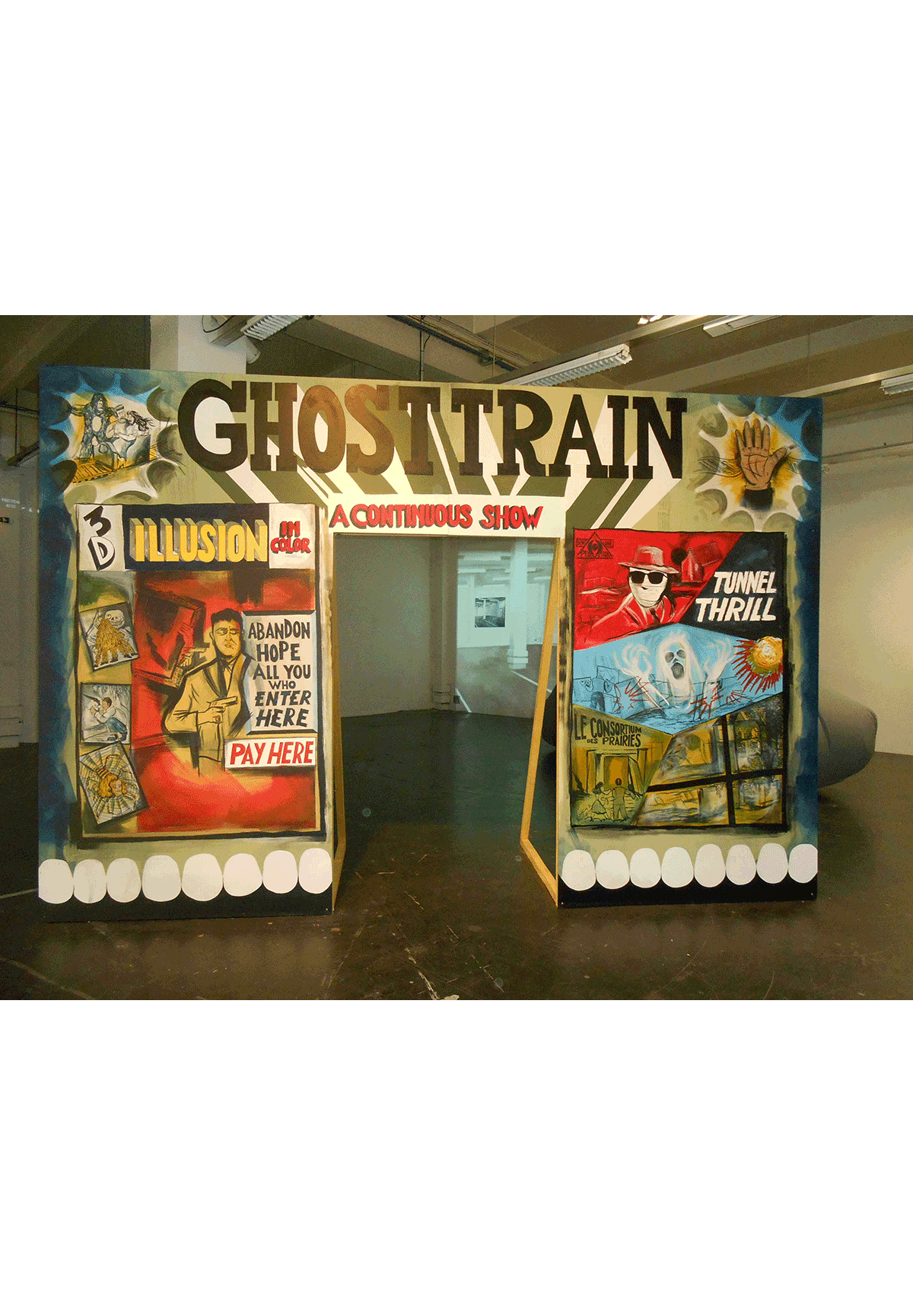

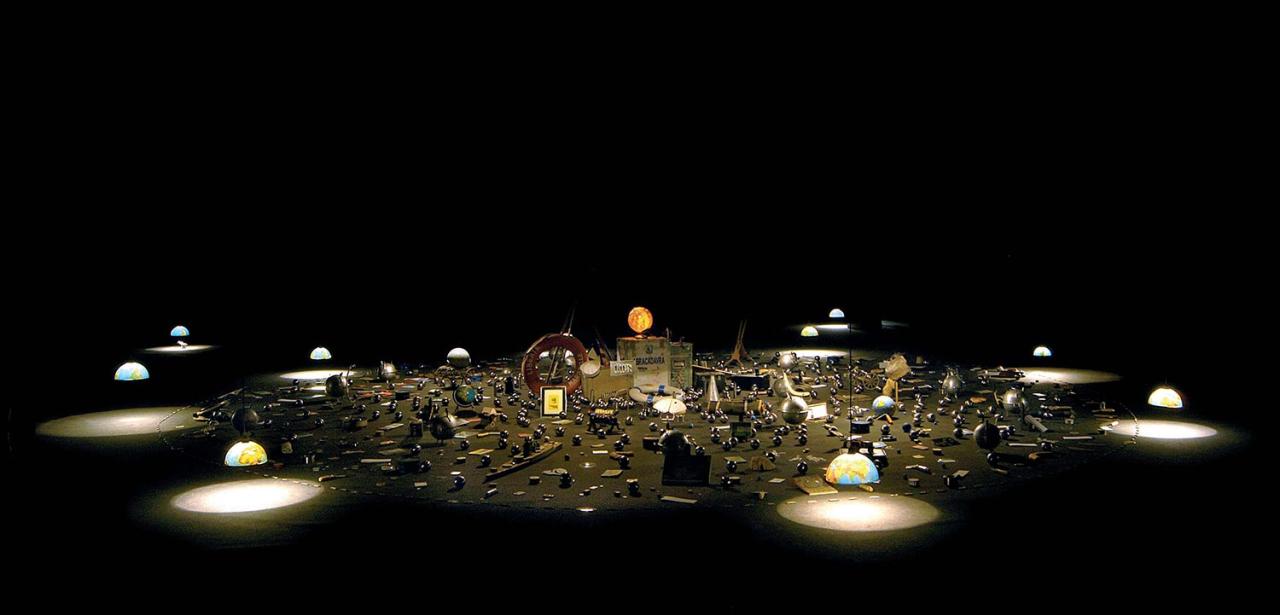

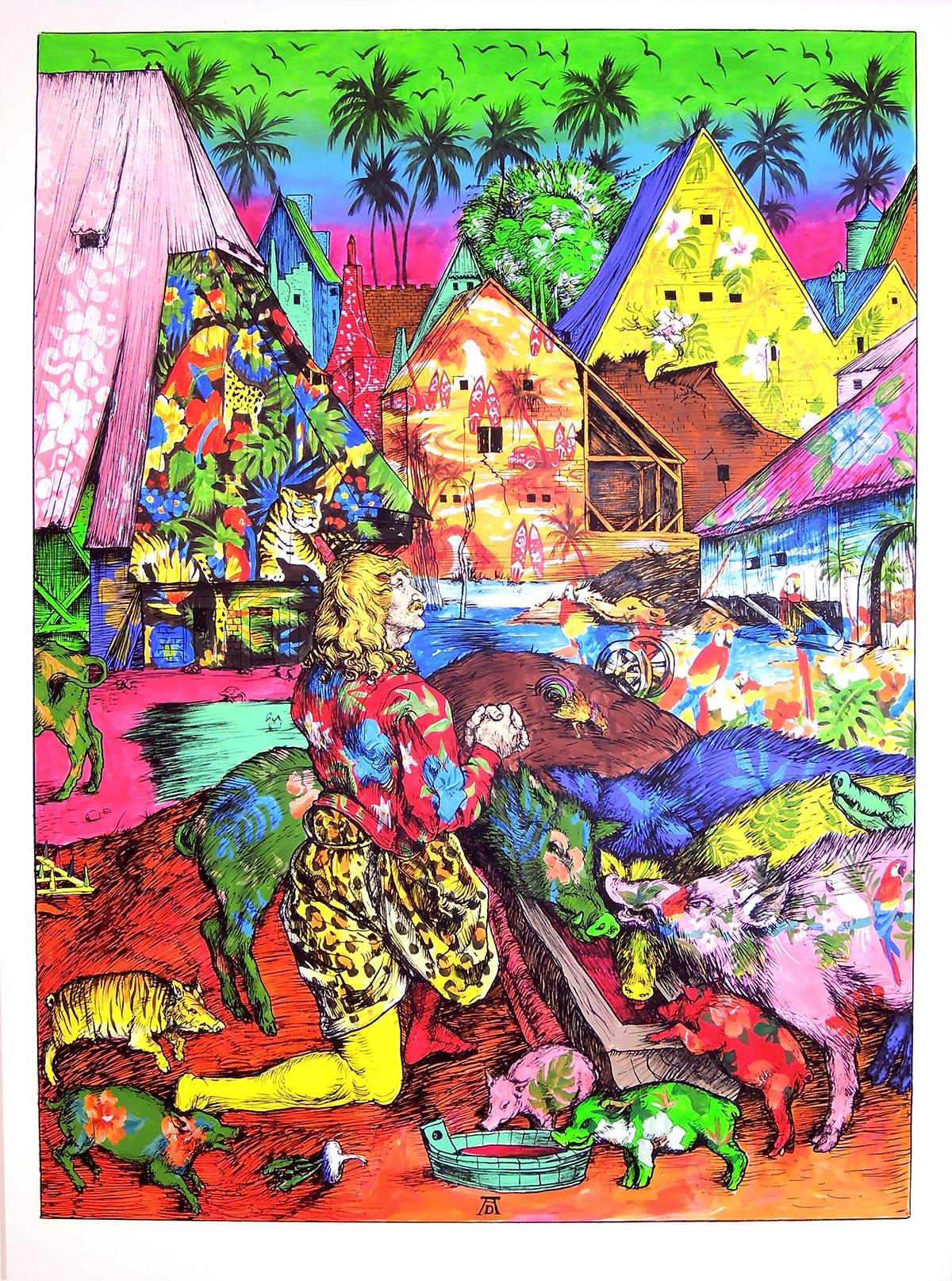

Of course—and that’s the nature of the thing—if it were another moment, another time, a starting point that wasn’t a painting by Liron but Paint It Black, a work in corrugated cardboard by Sylvie Réno, (which is as much an image as a sculpture), then everything would have been different. In front of John Cornu’s butcher’s blocks, magnificent black solids, temporal landscapes testifying to the work of a life, the encounters here would be equally delightful, amusing and offbeat. There would be Vagues à l’âme [Restless] by Florence Doléac, a constellation of boxes by Philippe Favier, the brightly colored paintings of Valérie Du Chéné and Philippe Fangeaux, not so far from the 23 acrylics Dürer color by Frédéric Clavère, which reinterprets icons from popular culture and art history, exposing society’s absurdity. And finally, a room filled with Camille Lavaud’s “cinephile” drawings. The references sparkle. A completely different exhibition, different story, different text...for another time or another life.

Notes :

1 Émilie Flory, FractopométrieTM, une collection en jeux; publication and exhibition protocol using the collection at Frac Aquitaine, 2005. A nod to Georges Perec and the OuLiPo workshop of potential literature.

2 “J'aime les gens qui doutent, les gens qui trop écoutent leur cœur se balancer.” From the song: Les gens qui doutent, by Anne Sylvestre, from the album Comment je m’appelle, 1977.

3 Georges Perec, Tentative d’épuisement d’un lieu parisien, published in 1975 for the magazine Cause Commune, first released in 1982.

4 The advantage of an imaginary exhibition is that you can do whatever you want: add side rooms, put things up, take things down, ad infinitum. Anything’s possible.

5 Title of many of the artist’s pieces.

6 From Spleen by Charles Baudelaire, “Quand le ciel bas et lourd, pèse comme un couvercle,” in Spleen IV, Les Fleurs du Mal, 1857.

7 In thinking of these two artists together through line, color and pigment, the work of herman de vries* comes to mind as well, with his Musée des terres, a multicolor collection of earth from around the world. Part of this collection is held at Musée Gassendi in Digne-les-Bains, Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, not far from where I live, nor from Jean Giono.

* Respects the artist’s choice of lowercase.

8 Read Joy to the World by Antoine Marchand, October 2016, on Félicia Atkinson’s work for Documents d’artistes Bretagne, which I’m discovering while writing this, and which oddly responds to my reading of Christophe Clottes’ work, expressed in 2 pieces in 2021: Si seulement nous avions le courage des oiseaux (April 2021) and J’ai pris la liberté de m’asseoir (October 2021) for Documents d’artistes Nouvelle-Aquitaine.

9 ACAB is an acronym for All Cops Are Bastards, a slogan originally used in England in the 1980s during the miners’ strike, taken up by various protest movements such as the ZADists, anarchists, etc.

10 On walking, meeting and Bure, read Étienne Davodeau, Le Droit du sol : Journal d'un vertige, entre la grotte du Pech Merle et Bure, Éditions Futuropolis, 2021,

11 Henry David Thoreau, On the Duty of Civil Disobedience.

Huile sur toile, 130 x 97 cm

Vidéoprojection HD Loop 30 mn

Collection FNAC Paris

Exposition à Fotokino, Marseille, 2020

Vue de l’exposition Futur, ancien, fugitif, Palais de Tokyo (16.10.19 – 05.01.20)

Broderie, 30 x 45 cm

Installation, projection vidéo, dimensions variables

5 promenades filmées, 130 min, couleur, sonore

Carton ondulé, métal, environ, 100 x 52 x 80 cm

Billots de boucher, peinture noire et cirage, dimensions variables.

Vue de l’exposition, Galerie Anne de Villepoix, Paris.

Coll. CNAP, Ministère de la culture et de la communication.

Photo : John Cornu.

7 tapis de moquette de laine (4 x 4 m),

7 plaids de moquette imprimés ou bâches imprimés (2 x 2 m),

7 balles en PVC gonflable (diamètre 95 cm), 21 traversins (1,40 m)

Installation d’objets, vue de l’exposition Géographie à l'usage des gauchers, Musée d'art contemporain de Lyon, 2005

Photo : macLYON - Blaise Adilon, © Adagp, Paris

crédit photo François Deladerrière

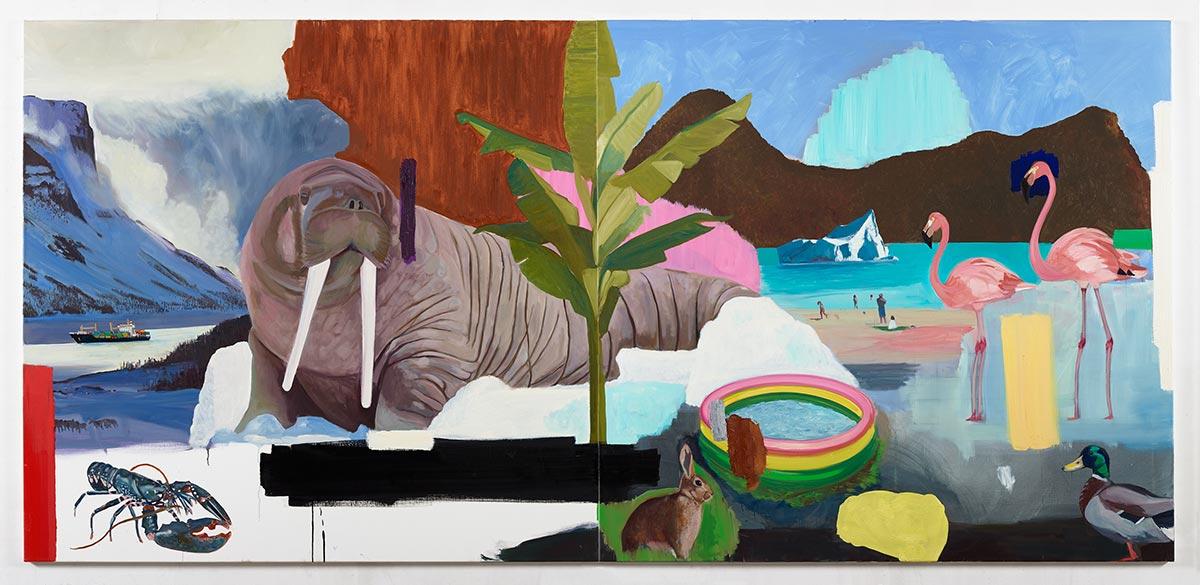

Huile sur toile, 160 x 340 cm

Série, Acrylique sur papier bambou, 162 x 120 cm