Against the In-Built Obsolescence of Other Images

Our globalized world is forever extending its logical systems involving the aspiration and obstruction of information, and our communication-bound society, focused on imagery, mainly serves more or less opaque economic interests which tend to divide the public and mould it as a “ready-to-consume” audience. The development of new technologies has also increased a freedom of production and access to information as much as it has stepped up strategies of hierarchization and inequalities in relation to its utilization 1… And at the top of these technologies, pride of place goes to the Internet, that hub of production, immediate archives and data information, which, a little bit more each and every day, bolsters the intermeshing of the public and private spheres. In refusing to be the ventriloquists of these channels which centralize information, and even though they represent epiphenomena, forces of opposition are becoming organized—free media, social movements, hacker communities. Beside them are artists who make their way into the informational mechanics underway and try to influence the dominant methods of public representations. They work their way into the strata of visibility and the historic layers, and propose, as it were, a negative artistic medium of mass media, capable of inflating the edges, and bringing to our knowledge elements that have been extinguished, swathes of forgotten history, hidden presents, and stifled affects. And participating, among other things, to borrow the words of Piotr Piotrowski, in forming a “micro perspective [which] should rather make a critique of national subjectivity, and deconstruct the subject-nation, with the aim of defending the culture of Others against the national mainstream”. 2

These artists are especially interested in forces of repression and forms expressing resistance, displacements of populations and constructions of plural identities, phenomena involving territorial privatizations and markings of the public place, and treatments and activations of a collective history. Their works, which, for the most part, issue from the production of new images, restore bodies, voices and faces to sidelined communities, make us aware of the distinctive features of a place and the special nature of an event, create and arrange new edges, and advocate the right to a subjective representation.

If all of them give pride of place to process, encounter and investigation, these latter are merely methods composing the form produced, not their objective. Their way of thinking is more globally linked to ways of writing our contemporary geographies. It aims to go beyond the specific features of sites of origins and to produce a knowledge capable of transcending its own conditions and languages, and thus setting up forms of “complicities” 3 which sound out how the place of discourse, transmission (with its narrative structures, tropes, and cultural moorings), and the engaged trajectory have an impact on the object of their interest—a meaningful object in the documentary approach adopted by these artists—with a view to forging alternative tools the better to represent the present.

Taboo

Some people manufacture print-images of segregation policies. When the powers-that-be suddenly removed the communities set up in the Sangatte refugee transit centre in 2003, Benoît Laffiché brought in a camera. Responding to the haste of the evacuation, which was designed to ward off any eventual opposition, a long sequence shot was filmed the day after the camp closed. The image recorded the uprooting which had just run wild, trying to plug the violent nature of the event and thus promote an historical continuum. The artist produced this piece in the run-up to Sud Schengen (2006), a triptych of videos projected in containers which showed on-screen three places where migrants from sub-Saharan Africa heading for the Schengen zone made their journey by sea. Clinging to an inexorably blue horizon, these videos pay tribute to those people who have been “turned into” illegal immigrants. The persistence of the image lends visibility to the incongruousness both of these maps drawn in water and of the forces which repress attempts to infiltrate a territory rising up slap bang in the middle of these liquid boundaries.

Ian Simms, who was born in 1961 in South Africa, went into exile in England in 1983, and resides today in France, fuels his art praxis with his own personal history, his many different identities, and his political activism. He strives to create a dialogue between representations of historical narratives, large and small alike, to describe the complex power-plays which tug at a post-apartheid South Africa. When he returned to his native land ten years later, he experimented with what the Uruguayan psychiatrist Lya Tourn calls “the wild return of the absent (person)”. He then produced Si jamais je rentrais… j’habiterais dans un centre commercial/If I Ever Go Home… I Would Live in A Shopping Mall (2003), a film accompanied by a voice-over, that proposes a stroll in a shopping mall, which has become the only non-place where he can feel at ease. As part of another project, titled Establishing Territory, Ian Simms filmed a video triptych about security-related fables, in South Africa in 2006/2007: gated communities, suburban zones given themes based on the activities indulged in (golf, riding, etc.), compartmentalized and sterile architectures, and the “walking the farm” ritual, which consists in walking around your land in order to make yourself visible to and discourage possible squatters. These films which describe paranoid strategies of territorial divisions are accompanied by diagrams resulting from a recent sociological survey illustrating whiffs of conservatism in South African society. In another installation, titled Seuil/Threshold, the artist talks about the work conditions of labourers in South Africa by way of a specific historic event: the platinum miners’ strike at Marikana in 2012, ending with the deaths of 34 of them, whom the police had opened fire on. Thanks to the support of a French researcher, Ian Simms gained access to a large number of documents coming from the main South African miners’ trade union, which he overlapped with his own objects collected in a large multi-media installation composed of Genet-like para-texts, (please include, forward, preface, text, footnotes, postface, etc.). All aiming towards a breaking point: the image of the first bullet fired by the police and caught by television which the artist managed to extract by using the ore coming from the platinum mine in question. By updating societal strategies of marginalization, the artist and film-maker Frédérique Lagny has in her turn produced several works in Burkina Faso, including the film A qui appartiennent les pigeons/Who Do the Pigeons Belong To? (2012), which is based around two figures, that of the storyteller and that of the sleeper, and explores the construction of the character of the madman, a prism which sends us the diffracted reflection of identities marked by a colonial history which is here ingested and re-depicted.

What might be, what might be a resistance4

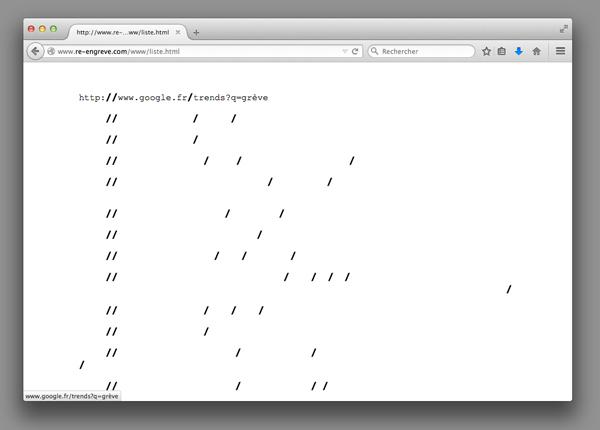

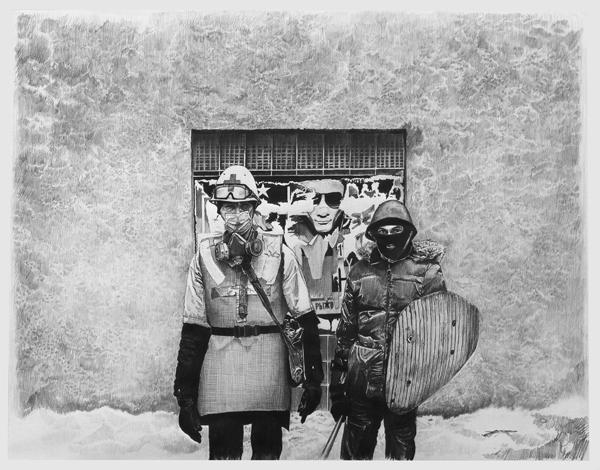

Other artists are working on the representation of forms of protest. In his Re: en grève/Re: On Strike, Serge Le Squer lists the web pages which deal with strikes, which he commits to silkscreen prints and engravings on glass. In Beirut, he photographed a guffaw of laughter with a black eye, received during a demonstration (in 2002), and caught images of demonstrators in front of the American Embassy which he ironically titled Le seau bleu/The Blue Bucket named after the protective seal worn by a demonstrator, referring to the blue helmets worn by UN peacekeepers. These images taken on the run, attempt to present the phenomenon of the riot, that spontaneous, urgent form which is so hard to capture. Johann Rivat, for his part, chose to represent this using graphite and paint in a series which he titles Uncivilized. From the demonstrations in Taksim Square, Istanbul, in May 2013 to the more recent ones in Hong Kong, he uses a mix of press photos to depict the event, altering, in so doing, the original media treatment. He is less interested in the reasons for each struggle, so he puts himself on the right side of a universality that represents these struggles which, removed from their context, have something majestic, not to say romantic, about them because of their format and their subject, like history paintings of war. Graphite, which is at once a tool for meditating about the world and forming the way we look at things, underpinning a praxis underlying painting (a “jurisprudence”, in his own words), immediately and irrevocably establishes a possible backdrop, incorporating a line of thinking in it, while the paint shapes it, gives it (plenty of) colour, increases the anonymity of the figures (eyes like holes) and adds anachronistic features (a knight).

Martine Derain supports freedom of movement for the people of Palestine. When she was invited by the French Consulate General in Jerusalem (France’s representation in the “Palestinian territories”) to come up with a work for the public place, in collaboration with Dalila Mahdjoub she produced En Palestine, il n’y a pas de petites resistances/In Palestine, There Is No Minor Resistance (1998-1999). In response to the major fragmentation of the territory and the permanent control of the movements of Palestinians, the two artists took advantage of their own possibility, as foreigners, to move about freely; they made 30,000 bus tickets (printed and bound by hand) which a Palestinian transport company agreed to use on an official basis, thus enabling passengers to cross the various checkpoints. Using the same format as the originals, the tickets showed new images and texts resulting from the artists’ many encounters with the Palestinian population.

With Drina (2011-2012), Guillaume Robert opted for a form of re-enactment: in a project which brings videos and photographs together, he documents the reconstruction of one of the objects cobbled together at that time by Bosnians to make up for the shortages created by the state of siege of the army of the Serbian Republic of Bosnia. With the help of one of the founding fathers of those survival kits—a retired Bosnian mechanic—the artist duplicated a raft moored in the river Drina, meant to serve as a mini hydro-electric power station. Through this process of reproduction, he thus re-enacted that do-it-yourself spirit marking resistance to occupation, and paid tribute to it, affirming history and continuing it, and, after the fact, lending the event both an origin and an identity.

The different representations of acts of resistance, above-described, do not have the effect of neutralizing these acts, but, on the contrary, they kindle them. For let us bear in mind, with Jacques Rancière, that representing does not mean positioning oneself “in the place of” or “lying about the truth of things” 5.

Relational Geographies

“The past is contemporary with the present because the past is formed at the same time as the present: past and present are superposed and not juxtaposed. They are simultaneous and not contiguous”, 6 wrote Françoise Proust about Walter Benjamin’s conception of time. Serge Le Squer revisits History by focusing on observing the unevennesses of its surface. In Un camp, cinq stèles/One Camp, Five Stelae (2009), he describes way the use of a place develops, turn by turn from a centre where Spanish Republicans, Jews and Gypsies were housed, interned, and assembled, to a guarded reception centre for collaborators, a German prisoner-of-war camp, a transit camp for harkis (Algerian soldiers who fought with the French), and an administrative detention centre for foreigners without the right papers. Accompanied by a documentary book about these successive incarnations, the video offers an outdoor tracking shot, taken from a vehicle whose dull engine noises underscore the depopulated look of the landscape filmed, while the fact of keeping the camera equidistant from the object filmed ends up by creating a break. The camp is strewn with stelae, resembling ancient menhirs, which stand, solitary, within an emptied, destroyed setting, which is given structure by nothing more than the presence of wind turbines and recently planted trees. Like the fragments of a scattered monument, the stelae become the blatant sign of an unresolved history. In another video, Pas à pas, les arpenteurs/Step by Step, the Surveyors (2003), Serge Le Squer this time proposes a stroll in the historic layers and traces of conflicts which forge the city of Beirut. The video alternates between an interior space—a destroyed Beirut cinema which two men are trying to measure by hand—and an exterior space—with, on the one hand, a city which is a permanent construction site where people are filling in the holes dug by war, and, on the other, an archaeological site where there is an in-depth excavation of its past. The beauty of the film results in large part from the state of tension of the forces present: the macro scale of the massive destruction rubs shoulders with the micro scale of people doing their utmost to rebuild. The excavation of the film reels in the cinema endlessly duplicates our own position as spectator. The film form underpins the effort to repair things which it presents. The musical whisper which bolsters the image calls to mind the seething nature of the living world, before it is once again absorbed by the noises of gunfire and the underground darkness of the final scene.

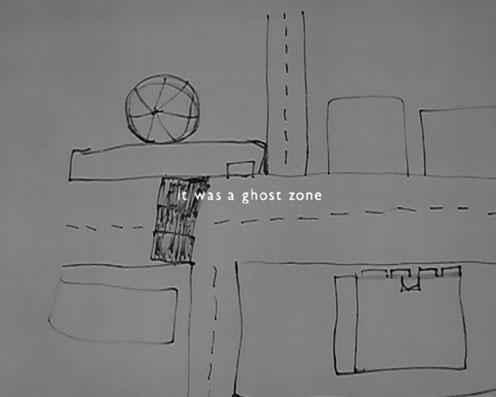

Screened at the Mucem7 as part of an exhibition associated with Morocco’s heyday, the film Pour autant qu’un musée…/As Far As A Museum… (2014), made by Martine Derain with the film-maker Jean-François Neplaz, shows the audience of the association which invited her, La Source du Lion,8 the tale of the investigations undertaken by the artist about the recent history which unites the two cities of Marseille and Casablanca. In one of the videos screened, she captures at nightfall, using a light recording system, scenes of everyday urban life. Martine Derain takes up a modest stance, respectful of the evidence that she is given and careful not to use the archives she has been given for her own ends. In particular those of Armenian photographers—studio portraits made with photographic chamber of Moroccan workers, intended to be sent to their families back home in the bled (boondocks),--which she saves from being pulped and 2,500 of which she has managed to get the archives of the city of Marseille to acquire. A way of organizing a place for émigré populations within areas legitimizing France’s history. In her work, Martine Derain traces examples of “counter-cartography”,9 which would no longer be unambiguous and would not serve geopolitical interests, but affective maps, drawn using minority perspectives and subjective narratives developing a whole host of geographical experiences of and approaches to migration. Irit Rogoff understands this geography as “a concept, a system of signs, an organization of knowledge established in the centres of power. By introducing”, she continues “into the arena of geography questions of critical epistemology, and subjectivity, and issues to do with the onlooker, we shift the questioning from the centres of power and knowledge, and the naming of margins, towards a site where new and multi-dimensional knowledge and identities are forever being formed”.10 The maps which Till Roeskens constructs using a multiplicity of approaches are “narrative”. Whether he is asking Palestinians clutching ballpoint pens to sketch the environment surrounding them in the camps where they were held prisoner (Vidéocartographies: Aïda Palestine, 2009), or whether he is performing live the history which others have entrusted him with (Plan de situation: Consulat Mirabeau, 2012) by drawing on the floor the trajectory and geographies of each one, the artist is aware of geographical narratives as active tools used for reconstructing memory. He put on this latter performance at the very site where he collected the stories, in order to “give them back” to those primarily concerned. By reworking live the individual narratives in the first person, he incarnates the filter. The mobile and unstable nature of the maps which he communicates to us is enacted by the choice of method involving a light, not to say precarious representation: a ballpoint pen which draws or chalk on the floor, the makeshift projection installation in the open air.

“Civilization of the image? In fact, this is a civilization of the photo, where it is in the interest of all the powers-that-be to hide images from us, not necessarily hiding the same thing from us, but hiding something in the image from us. At the same time, on the other hand, the image is forever trying to pierce the photo, and get out of the photo. We do not know how far a real image can go: the importance of becoming visionary or prescient. Awareness and a change of heart do not suffice […]. Sometimes it is necessary to reinstate the lost parts, and rediscover everything we do not see in the image, everything that we have extracted from it to make it “interesting”. But at times, on the contrary, it is necessary to make holes, introduce voids and blank spaces, rarify the image, and get rid of a lot of things that we had added to make us think that we were seeing everything.”11

By way of the production of static and moving images, the works described above pinpoint marginal phenomena which prompt the viewer to adopt an extroverted way of looking at things. It is less important for artists to address problems from a given geographical place than from the regeneration of a formal language suited to accommodating unusual and even hostile new conjunctions (between people, countries, institutions, and religions). Rather than being satisfied with fixed and “naturalized” spaces, these artists propose remaking new territories, which are migratory, subjective, and heterogeneous.

Author’s note

This essay is a response to the invitation from the Réseau documents d’artistes to propose a cross disciplinary/transversal reading of their different documentary collections. It makes, perforce, a break/cut/(cross)section. It is a digest of my different discoveries and the short cuts taken. The working process involved goes beyond it. It is by nature non-exhaustive, limited to the page in order to offer a dynamic reading, but also through a desire to bolster its coherence and the angle of analysis chosen. With this additional note, I wanted to draw attention to the earlier route taken through the works of other artists to whom I pay tribute: the ethnographical works of Sharon Kivland and Ymane Fakhir focusing on depicting the female condition, Suzanne Hetzel’s work involving photographic documentation of empty places affected by economic downturn, Fabienne Ballandras’s reproduction of images proposing an alternative to the way the media represent forms of conflict, resistance and protest, Rajak Ohanian’s photographic series illustrating the history of the Armenian people, Jean-Baptiste Sauvage’s actions focusing on strategies aimed at marginalizing bodies in the urban space, Catherine Rannou’s long-term project which is part of the organization of private areas for sailors with difficult lives who are members of a Seamen’s Club, and last of all, Jean-Benoît Lallemant’s work involving the mechanical encoding and appropriation of cartographic technologies.

Bibliography and hyperlinks

1 - See in particular Michel Guet, L’infini saturé, Espaces publics, pouvoirs, artistes, Les éditions Atelier de création libertaire, 2008, and Antoinette Rouvroy, “Le nouveau pouvoir statistique. Ou quand le contrôle s’exerce sur un réel normé, docile et sans événement car constitué de corps " numériques”, in Multitudes 2010/1, N°40 : Big Brother n’existe pas, il est partout.

2 - Piotr Piotrowski in Géo-esthétique, edited by Kantura Quiros and Aliocha Imhoff, éditions B42, Parc St-Léger, l’ESACM, Le peuple qui manque, ENSA Dijon, 2014, p 130

3 - The anthropologist Georges Marcus quoted by Irit Rogoff in Geo-Cultures, Circuits of Art and Globalizations, in Open, 2009, N° 16: The Art Biennial as a Global Phenomenon

4 - When the Renault factory at Billancourt closed in 1992, leaving thousands of workers high and dry, Marguerite Duras published an essay in which she imagined a project consisting in displaying on the pediment a list of the names of all those who worked there, “to see, to see, what a proletarian wall would be, would be”. A monument to workers who prefer the display of a count of the individual people forming a massive and anonymous worker corpus to the display of that corpus . The repetition of the words re-asserting their meaning, at the same time as giving rise to a syntactic tremor, lends the sentence all its strength.

5 - Jacques Rancière, “Le travail de l’image”, in the magazine Multitudes 2007/1, n°28.

6 - Françoise Proust, L’histoire à contretemps, Hachette, 1999, p.36. Quoted in François Dosse, “De l’usage raisonné de l’anachronisme”, an essay first published in EspacesTemps n.87/88, 2005 “Les voies traversières" de Nicole Loraux, p.156-171, p. 10.

7 - Musée des civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée, Marseille

8 - La Source du Lion is a platform for experimentation, production and artistic exchanges based in Casablanca

9 - Irit Rogoff, Geo-Cultures, Circuits of Art and Globalizations, in Open 16 : The Art Biennial as a Global Phenomenon

10 - Irit Rogoff, Engendering Terror, 2005, traduction de l’auteur.

11 - Gilles Deleuze, L’Image-temps, Cinéma 2, Edition de Minuit, Paris, 1985, p.32-33

Video, 10 min - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Video Installation, 3 containers

Still from the film

Two-part video, 6 min. Still from the film

WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Installation, 2 two-part videos, 11 graphs, model.

Exhibition view at Pavillon Lanfant, Aix-en-Provence

Two-part video, 10 min - Extract from the installation "Establishing Territory"

WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Graph, inkjet printing, 24 x 18 cm, extract from the installation

Platinotype, Collection FRAC Poitou-Charentes,

extract from the installation "Seuils", mixed media, 2013

Video, 39 min. Still from the film

Still from the film - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Installation, printed screenshots, website, silkscreen printing, etch glasses. Still from the website

Etch glasses and silkscreen printing, 63 x 44 cm each

Video-prints, 108 x 47 cm each

Video, 60 min and documentation (one chronology, one map of the camp, a letter from

the Ministre de l’Intérieur to the Préfet des Pyrénées-orientales)

Video, 26 min. Still from the film - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Oil painting, 195 x 260 cm

Graphite on paper, 50 x 65 cm

Intervention in the public space, in collaboration with Dalila Mahdjoub. Printing of bus tickets loose-leaf notebooks, 2 colour offset printing, 85 x 40 x 13 mm, 300 notebooks of 100 stapled, precut and numbered tickets.

Intervention in the public space, in collaboration with Dalila Mahdjoub. Printing of bus tickets loose-leaf notebooks, 2 colour offset printing, 85 x 40 x 13 mm, 300 notebooks of 100 stapled, precut and numbered tickets.

Intervention in the public space, in collaboration with Dalila Mahdjoub. Printing of bus tickets loose-leaf notebooks, 2 colour offset printing, 85 x 40 x 13 mm, 300 notebooks of 100 stapled, precut and numbered tickets.

Video, 40 min, in collaboration with Jean-François Neplaz. Public meeting, Casablanca/la Source du Lion, April 2014. Photo © Corinne Troisi - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Video, 23 min, photograph, mini hydroelectric plant. View of "Lever une carte, parcours d'art contemporain dans la vallée du Lot", MAGP, Cajarc, 2012 - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Photograph, tarpaulin printing, 185 x 160 cm

Video, 46 min, 2009. Still from the film - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Open air performance, and a cartographic sidewalk chalk drawing - WATCH THE DOCUMENTARY AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Video, 10 min

video diptych, 7 min

video diptych, 10 min

Video, 39 min

Video, 60 min (extract 10 min)

Video, 26 min

Video, 40 min, in partnershop with Jean-François Neplaz

Video, 22 min 30

Film, 46 min