Putting images to the test

Putting images to the test

What is an image? To answer this question, there are many books one could read. One could also simply look at a photograph – this one, for instance, taken from Olivier Amsellem’s 2014 series, Sans laisser de trace. It shows a wall that, once covered with images, is now just animated by their traces and remnants of adhesive tape. These traces are more or less obvious and more or less distinct, they overlap and refer to different temporalities. But all of them show, negative-like, that an image, before being a subject, is first and foremost a frame and a mount, therefore an object. Producing an image is framing reality or the imaginary, in the figurative or the abstract, and turning this extract into tangible reality.

Representation in question

Two works help support the materialistic approach of image that insists on its physical and structural characteristics. The first one is Hervé Beurel’s Collection publique. Started in 2003, this long-haul series presents geometric compositions that evoke French post-war abstract art. They are not, however, anachronistic paintings, but mural decorations on buildings that were built between the 1960s and 80s, which Beurel framed – and sometimes retouched so as to erase the details that disrupted their homogeneity – in order to take them out of their context and turn them into pictures. Collection Publique confirms the role played by framing in Beurel’s work, he who has often used the camera to divide reality and move towards abstraction.

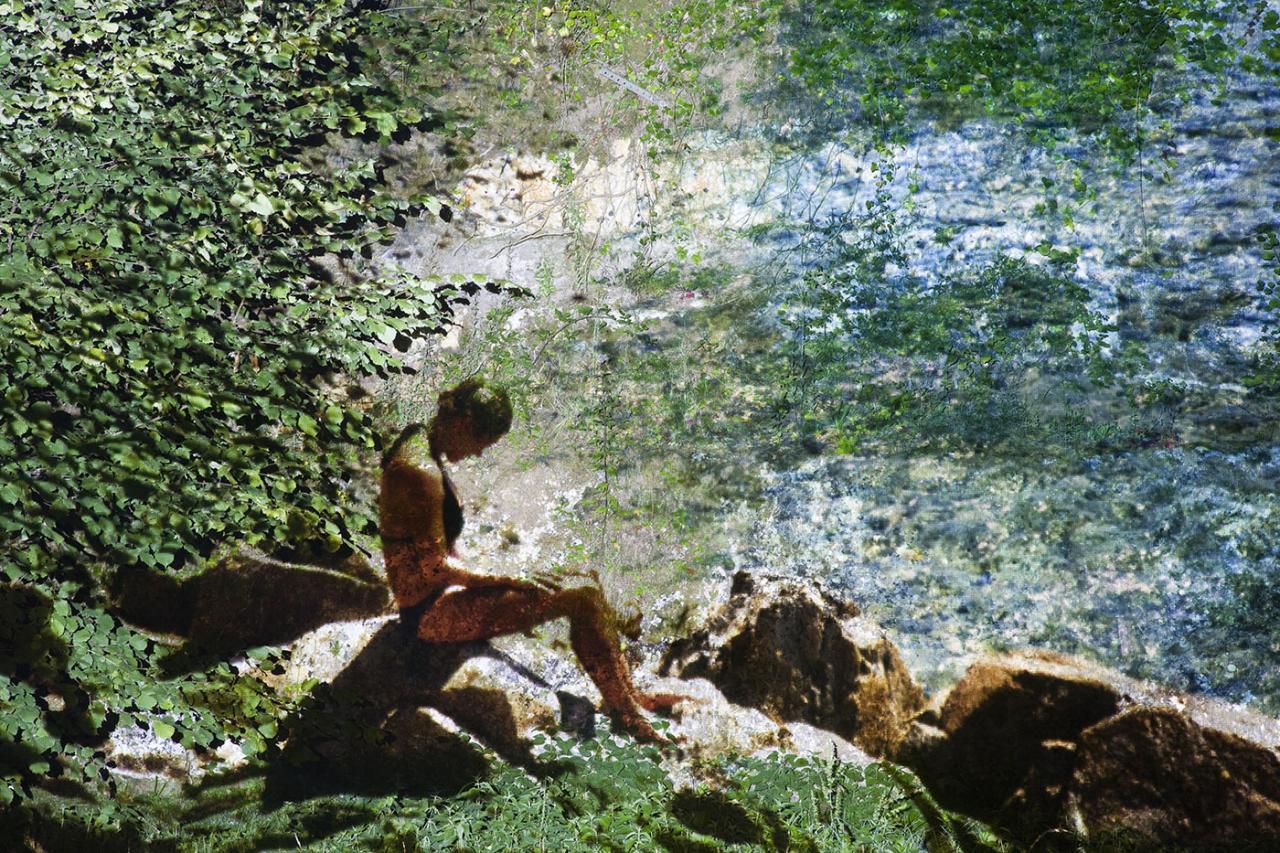

The second work is Olivier Crouzel’s Vacances rupestres .Created in 2009 by projecting photographs of beach holidays onto the exterior walls of Combarelles painted caves, in Dordogne, this series is based on the contrast between the lightness of images, in every sense of the word, and the cave walls’ matter, weighted by thousands of years. Sensitive to the moment of projection, which is an integral part of the œuvre, this symbolic dimension becomes concrete once one comes face to face with the photographs taken by Crouzel. He uses the rocks’ crevices, and vegetation too, to give substance as well as an ancient aspect, to shots that seemed devoid of them.

Examining the notion of image thus justifies pointing out its material components. This enables us to distinguish it from the mental image and to compare it to the English-language notion of picture. Unfortunately without a French equivalent, this word nuances the word image which, also in English, refers first to representation, apart from its material conditions. Yet can we shrug off the question of representation, whether relating to a real topic or to a simple abstract motif? In other words, can a common wooden board, which is also in a way a frame and mount, be an image?

The thresholds of images

Such is the question that Sébastien Maloberti seems to be asking. On used boards, he makes prints so diaphanous they are at times barely perceptible. Some of these prints include geometrical signs, sometimes photographs, while others are reduced to barely-coloured beams and halos, or even traces from other boards. The artist sands down and whitens his mounts, but also keeps an eye out for printing incidents that leave random marks. For one of his Sans titre (2014) presented in the 2015 exhibition La Fille de l’Air at Bikini, in Lyon, Maloberti even settled for leaving a board treated with acrylic resin and bleach all summer in the sun, under the roof of his studio, producing a result that is difficult for the eye to perceive. In 2016, at Tuttlingen’s Galerie der Stadt exhibition Nouvelle Coutume, in Germany, his œuvre entitled The New Custom’s Day was an aluminium plaque partially engraved and lightly spray-painted to evoke a wall calendar. The lower part represented the grid for days of the week while the upper part was only an image of the changing reflections of its surroundings.

Maloberti’s liminal or circumstancial images shift our thinking. Through them, the question being raised is not so much “what is an image?” as “when does it start being an image and when does it stop?” Are there images that are not fully images yet and others that are no longer images? Artists explore these thresholds and test the limits of images. Simply put, they put them to the test.

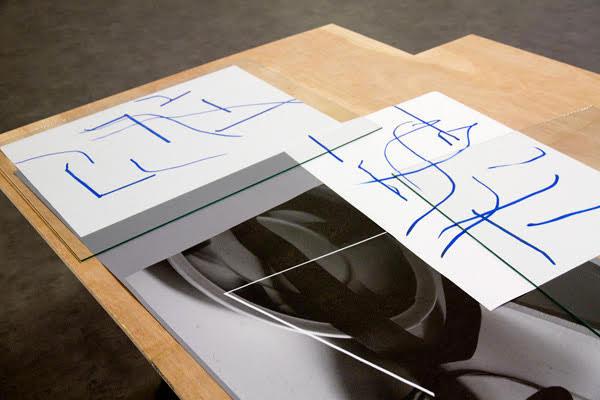

Jesús Alberto Benítez works with drawing, painting, photography and installation, but his œuvre’s common thread seems to be the forming of images. His photographs insist on how they came to be. They represent his studio, the tools and materials he uses. A recent series of photographs, Untitled (2018-19) shows us fragments of his computer screen, where the texture of the image appears as a digital file. His drawings are readily cursory: a few more or less spontaneous strokes that seem to want to combine to form an image. His paintings are often just the imprint of a gesture, as in covering or scraping. And his contribution to Thomas Fougeirol and Jo-ey Tang’s project entitled Dust : the Plates of the Present, acquired this year by Centre Pompidou, takes on the radical shape of photograms, where a simple fold in the paper, sometimes tapped against the enlarger, creates an image.

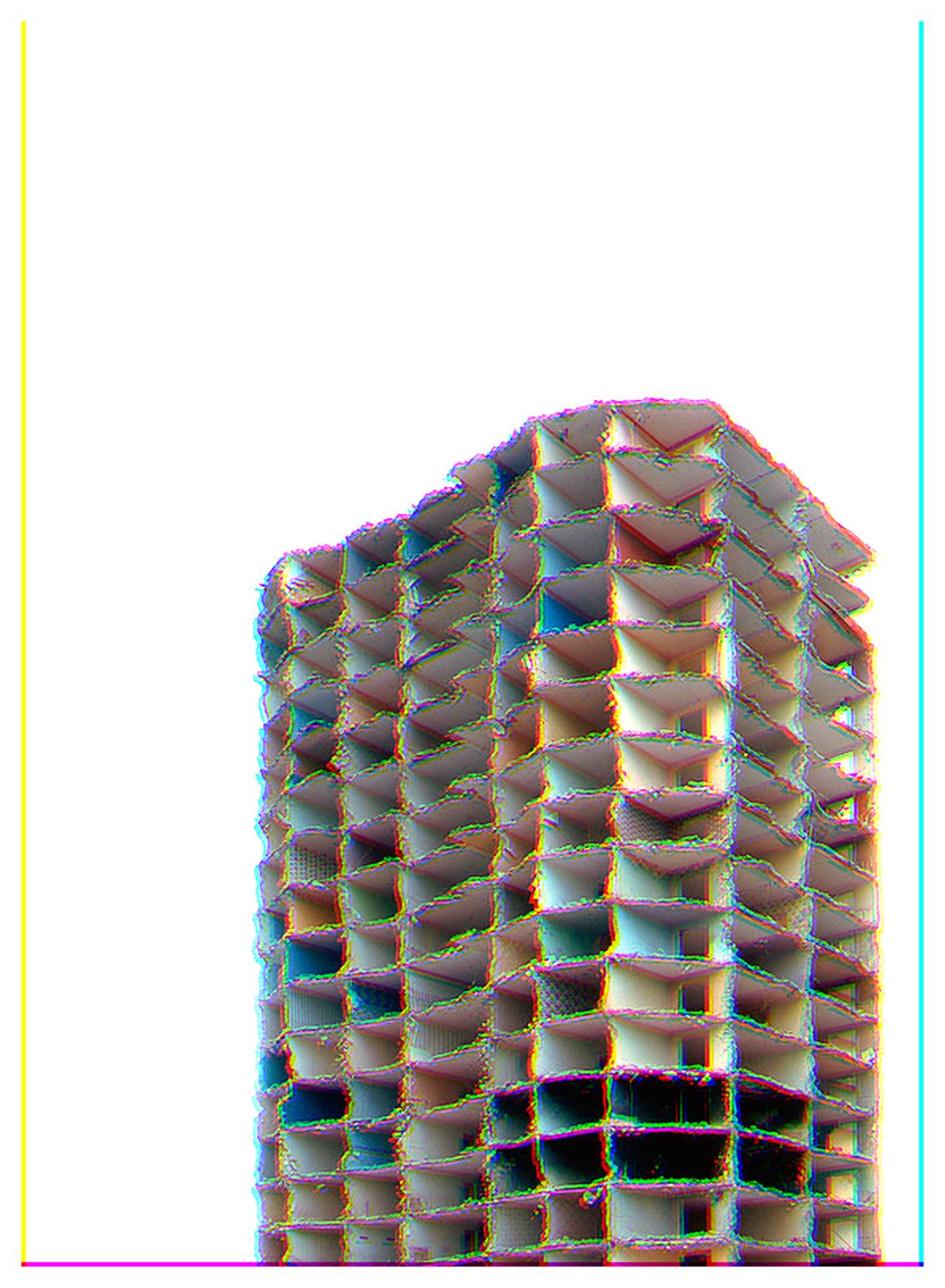

With Benítez, the image’s point of appearance echoes its point of dissolution. It is perceptible in Ibai Hernandorena’s mises en abyme on architecture and urbanism, on their obsolescence and failures, whether it be French suburbs housing estates or Spanish projects stopped by the 2008 credit crisis. Several of these were shown at Villa Arson in Nice, in 2015, in the exhibition entitled l’Après-midi, curated by Matthieu Mercier. Glissements (2015) is a photograph found online of a high-rise whose façade was removed. To emphasize the building’s imminent destruction, Hernandorena deconstructs the image by shifting the reds, greens and blues that are usually together in chromatic synthesis. As for Falls, a video created that same year in the Spanish ghost town of Sesena, it is a slow twelve-minute tracking shot around a roundabout and its fountain that resembles Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater (1935-39). It is the result of a shot-by-shot dissolve that preserves the fluidity of the video but also produces a liquefying effect of the image reinforced by the soundtrack of falling water.

These works are on the thresholds of image. Others are more like a process and bring the image into play in order to test it. For all that, are they trying to exhaust it?

The image’s potentials

The answer is not so obvious if we look into Pierre-Olivier Arnaud’s work. In 2016, his exhibition Un autre halo (play still), at galerie Art: Concept in Paris, included, hanging from the ceiling, a decorative paper ball partially discoloured by the sun. Are the images surrounding it also degraded? It sure seems so. Printed on poster paper, directly glued onto the walls whose reliefs they hug, they look like details of elusive motifs. That is because, born from urban strolls or from other images, these photographs are subjected to a series of interventions that, though not systematic, alter the image: poor-quality print, scan, pixelization, mesh, enlargement, desaturation, etc. One of the walls is thus occupied by a large frieze created from a photographic detail of a sequined stage curtain, which the artist turned into black and white and into negative before repeating the image. Paradoxically, these operations do not impoverish the image but rather enrich it. Other elements appear, traces of its successive generations, and displace its potential for projection, inherent to the nature of the photographed object, beyond mere representation.

Aurélie Pétrel also brings into play her images by reworking them, but, in this instance, from one presentation to the other. Following the protocol that emerged as a result of Polygone, her 2011 exhibition at galerie Houg in Lyon, and a glossary explaining it, she works with “latent shots” – photographs she archives, letting them go “fallow” in her “materials library” as 50x60 cm baryta prints, and which she “activates” when the time comes by confronting the image with the exhibition space or the time of the performance. The conditions for its appearance are decisive, but the image also experiences its own development, especially as the activations feed off each other. On several occasions, Pétrel thus activated, under the title Chapitre 1, a shot taken in 2008 in a glass-maker’s studio where the dark interior contrasts with the view of the Kobe bay and the backlit pieces of coloured glass. After having experimented, among other things, with its transparency – in 2015, in Dispositifs at Comédie de Caen – with its fragmentation – in 2017, in SoixanteDixSept Experiment at CPIF in Pontault-Combault –, the latest activations of this image, in a personal exhibitions at galerie Ceysson & Bénétière in Saint-Étienne in the fall of 2019, revealed its power of abstraction.

Public images

The aforementioned oeuvres of Maloberti, Benítez, Hernandorena, Arnaud or Pétrel have one thing in common: they are not obvious images. They throw us off and cannot be reduced to just any message. Though some, like Maloberti’s UV prints or Arnaud’s silkscreens, borrow their technique from visual communication. But they all appear to be the antithesis of public images that, whether commercial or political, are straightforward and try to be efficient. In the world of images, they have a specific status that has not escaped Vincent Bonnet and Driss Aroussi. Both have put it to the test. The criticism is no longer implicit, but head-on.

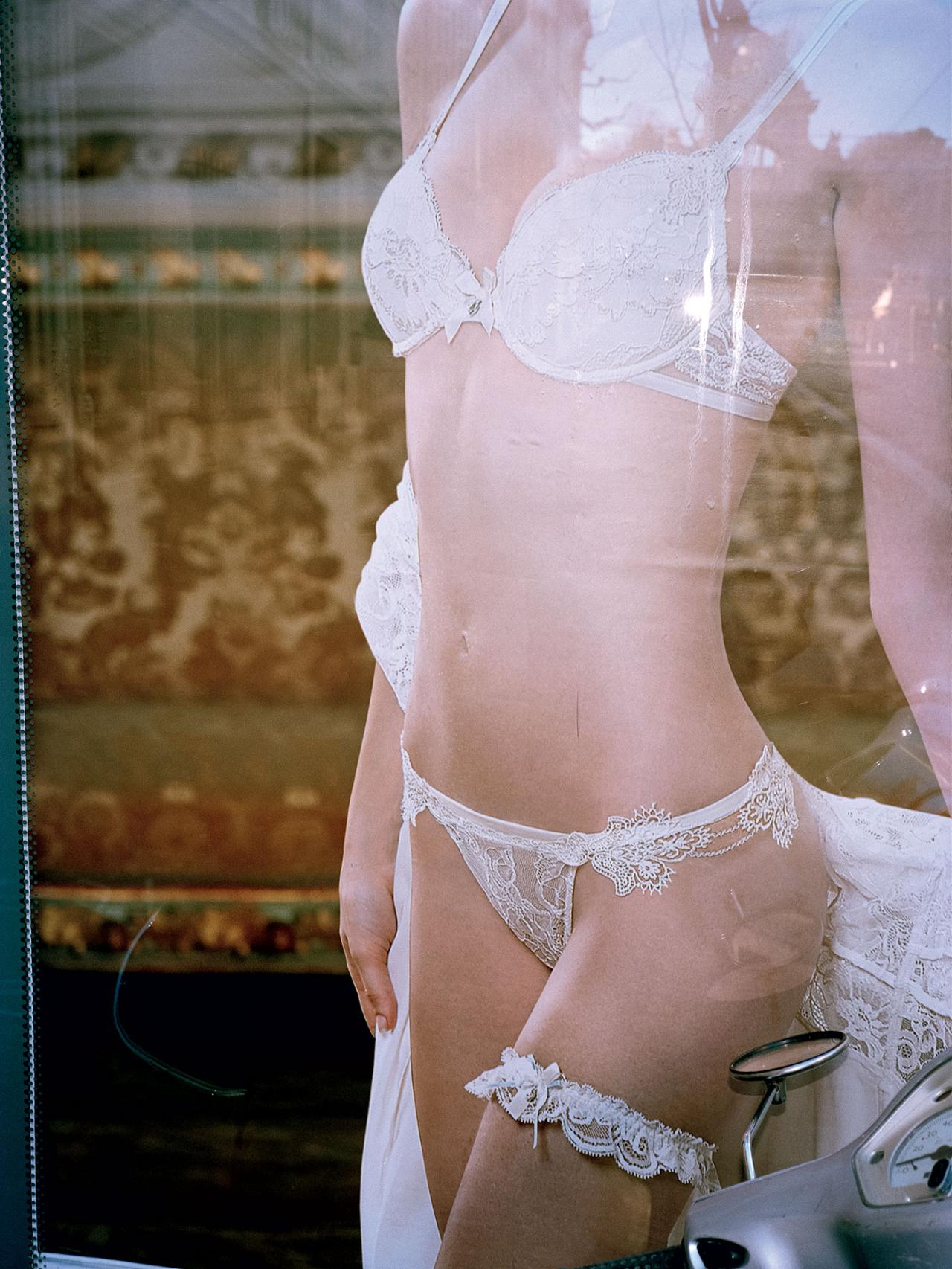

Bonnet, whose work mostly consists in injecting images into public spaces so as to invade the “media field”, has chosen, this time, to “simply” photograph details from posters. By focusing on faces and bodies, which he enlarges to a 160x120 cm format – the dimensions of the bills presented in JC Decaux light panels –, he seems to want to amplify the promotional rhetoric that idealizes and creates « hypersubjects », according to the title of his series, shown in 2015 at Vidéochroniques in Marseille. But his ambition is quite different, because Bonnet photographs these posters in situ, concentrating on whatever disrupts our reading of the image – urban overload, folds in the paper, reflections, graffiti and tears… – and thus unravels the fiction it tries to establish.

Driss Aroussi also captures these same images, also intending to question their efficiency. But his method is different, in that it entails rephotographing these advertisements, which have mobilized important resources, with a simple mobile phone. When he created the series in 2009-12, the phone imposed its texture and pattern, to which Aroussi also added the transition from colour to black and white. He pushes back the limits of these images’ denaturation by emptying them of their commercial role. Close-ups of “advertising faces”, his latest series, form a portrait gallery which he removes from the flow in which these images are usually caught by printing them directly from his phone through an enlarger he invented, and onto silver halide photographic paper.

As different as their works are, whether they explore their thresholds, bring them back into play or criticize them, all these artists challenge images. But they do not try to call them into question so much as to examine their possibilities. They go beyond the image’s mere representational function to explore its iconic potentialities. Put in danger, the image reveals itself. It is no longer the image of something, as is customary, but exists in itself and by itself.

Translation: Jessica Shapiro

Lambda print on aluminium and wood frame, 160 x 128 cm. Collection Frac Bretagne

Spray paint on engraved aluminium, 90 x 52 cm, Ph. Marc Dorazillo

Acrylic resin, paint and UV print on engraved wood, mounted on Dibond, 35 x 25 cm, Ph. Victor André

InkJet print, 127 x 84 cm

Extracted from the table top installation : drawings, photography, wood and fabric paintings, glass, 244 x 122 x 67 cm. Collection CNAP

Photogram, 41 x 30 cm. Extract from the « Dust: the plates of the present » project, Collection Centre Pompidou

Colour print, 110 x 150 cm

Video HD 16/9, sound, 12’30’’

Art : Concept, Paris, 4 june - 23 july 2016. © Claire Dorn. Courtesy of the artist and Art : Concept, Paris.

Art : Concept, Paris, 4 june - 23 july 2016. © Claire Dorn. Courtesy of the artist and Art : Concept, Paris.

Art : Concept, Paris, 4 june - 23 july 2016. © Claire Dorn. Courtesy of the artist and Art : Concept, Paris.

Fine art print on Baryta 310 g/m2 Canson paper , white margins, 41,5 × 52 cm.

Print date of the latent shooting : 2011

Curator : Audrey Illouz

Curators : Audrey Illouz, Nathalie Giraudeau, Rémi Parcollet. © Aurélien Mole

Galerie Ceysson & Bénétière, Saint-Etienne, 2019. Curator : Alexandre Quoi

Pigment print, 160 x 120 cm

Pigment print, 160 x 120 cm

Vidéochroniques, Marseille, 15 may - 12 september 2015

Silver print, 24 x 30 cm

Silver print, 24 x 30 cm