Proliferating Figures of the Other

Art praxis frequently comes across as an arena of self-expression, unlike other praxes involving subject construction, such as language learning, and a development of the knowledge and customs lying at the heart of educational institutions (family, school, and university). Within these institutions, everyone has to deal with the need to construct themselves by complying with a set of norms and prerequisites enabling them to incarnate the figure of the autonomous, rational and adaptable person, one who adapts to the challenges of contemporary society. For many years, artistic activities have held a fascination for me, because I thought that they required the subject to move away from the established and approved areas of knowledge and social skills—knowing how to be—and occupy an area outside: outside oneself, outside habits, and outside the real world. So for a long time I regarded the figure of the artist as one of my others, reckoning that I myself incarnated what was most ordinarily normal for a person born into late 20th century French society, in a socially and economically privileged context. My desire to work with living artists came about from this somewhat typical idea that their way of life and their way of living in the world were not on the same wavelength as mine. In a way, I projected another place onto art and artists, caught somewhere between exoticism and transgression, conveying a particularly naïve and romantic vision which I have been de-constructing ever since.

My research has taken different directions, exploring the production of many different psychic figures, genre construction, the brain’s plasticity, the body’s transformations, different states of consciousness, identification processes, affective relations, translation and interpretation practices, and forms of collectiveness and commonness. In this context, involvement in a curatorial activity has offered an especially important place to the challenges of the relation between artist and curator from the angle of this nagging question of the other, within us and outside us, the other with, against and between us. The use of us here instantly raises a barrage of questions, because it suggests the existence of a form of commonness or collectiveness, and we cannot immediately say what it consists of. The invitation to write a piece for Réseau documents d’artistes has given me a chance to develop issues which have punctuated my career, and which, today, are still at the hub of my research, my exchanges with artists, and the desire which drives my activities. I have allowed myself to be exercised by artistic approaches which I was not at all familiar with, by comparing them with other practices and other works which I have had experience of. It was important to start somewhere, and try and invent a way of circulating which makes sense, by choosing to propose extended relations between these works and these artists, but relations which nevertheless offer many different possible readings.

“Perhaps, on the extreme boundary of these tireless writings, or by piercing them with slips, there is just the cry: it is escaping, it is eluding them. From the first cry to the last, something else with it erupts, something which is its difference with the body, by turns in-fans and badly brought up, intolerable in the child, the possessed, the madman and the sick person—a lack of “good behaviour”, like the screaming of the baby in Jeanne Dielman, or that of the vice-consul in India Song.” 1

In going through artists’ works, I encountered figures of the other in their most numerous forms: exposed bodies whose gestures, words, songs and noises have paced my research. The works which feature in this essay display heterogeneous approaches to the portrait; not one genre but various genres, which take shape in media as diverse as photography, video, film, sculpture and dance. Other main threads have gradually appeared. The recurrence of forms of strolling in cities, revealing changing spaces in which forms of inequality and the violence of social relations are subject to questioning. The quest for new cultural, political and spiritual experiences, through which is revealed the challenge of going beyond oneself and the search for a movement beyond known territories. Last of all, the artistic approaches of all the artists introduced here question, in differing ways, the ethics within their praxes, and their authorial status: interpretation, collaboration, delegation, and co-creation are part of the creative and productive methods behind many of the works which will be discussed.

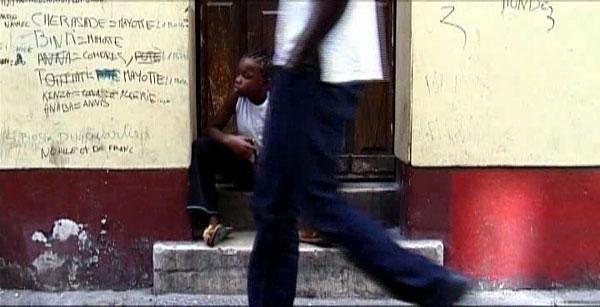

In her videos titled Eden ((Toifflati) (2005) and Mikaêla (2006), Flavie Pinatel lets herself be steered by an encounter with other women, one in Marseille, the city where the artist was born, and the other in Barcelona. Through these meetings, Pinatel proposes a portrait which is simultaneously incorporated within a relation to the person exposed to the camera, and to the neighbourhood in which each of these figures evolves. The shot takes the viewer into a stroll which develops in different relations of remove between the artist filming and the person filmed, and reveals the back-and-forth nature of very close-up shots, which take us very close to the faces of the figures, and shots which put the camera a few steps behind, marking time with the characters, and giving them more space. In Mikaêla, the sound mixes the capture of the shooting location and a wordless soundtrack made up of electronic sounds, and hallmarked by effects of vibration. These forms of interference seem to be with us in a possible movement between an external perception and an internal perception, both mental and dreamlike, which may be at once that of the artist, that of Mikaêla, and even that of the spectator. This possibility of seeing the portrait through constantly shifting viewpoints makes it possible to regard Pinatel’s approach as steered by a desire to unravel the hierarchies existing between the positions of the onlooker and what is being looked at. None of the subjects of the portraits produced by Pinatel has any brief involving exemplarity; on the contrary, they are asserted in the special nature they are given by anonymity and idleness. This idleness has nothing in common with the damned aspect of laziness and inactivity; rather, it describes a state which makes these figures available for an encounter and an experience, something they share with the artist herself: a shared condition of disposal and availability to the world, and to others. It would seem that Pinatel successively chose to make these portraits in places which perhaps lend themselves more easily to these experiences of contemplation and encounter. The places filmed in Marseille, Barcelona, Aubervilliers and Ramallah appear to share common features in the way the artist casts her eye over things: living, colourful, and politically incorrect places. 2

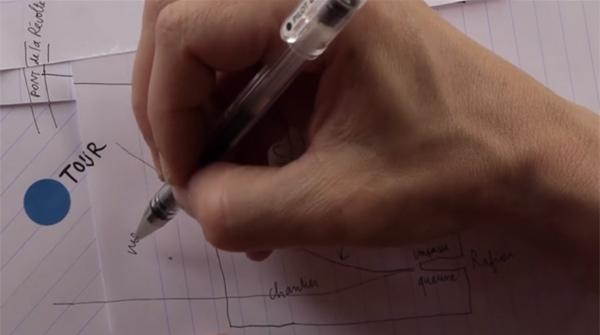

In their film titled Un Archipel, Till Roeskens and Marie Bouts describe a shared experience of an urban territory which is developing on the outskirts of greater Paris. They are both strangers to the towns in the Seine-Saint-Denis département, and they plunged into a discovery of this territory by having the possibility of criss-crossing it on foot, or using public transport, without trying to cling to any real mapping of the area, but by appropriating it by way of wandering experience and their imagination: “We were looking for passages, shortcuts, and detours. We were on the lookout for probable meeting points”. 3 This imagination which they have tried to construct together, and which they put across to us through their whispering voice-overs, has been shared in the film’s production process with a set of people met in differing circumstances during discussions with people involved in local culture, or simply friends. Bouts and Roeskens had become involved in that film with, as their reference, a very particular approach to cartography referred to by Bruce Chatwin in The Songlines. Chatwin had been interested in how the Aboriginals in Australia sang, “a way of singing your way” 4 making it possible to conceive of another relation to the territory and its forms of representation. Each encounter with an inhabitant of Seine-Saint-Denis invited to take part in the project thus developed around his or her movements in space, their perception, and their appropriation of the territory they lived in and the possibility of translating this by way of poetic words, sung and rhythmic. Un Archipel thus seems like a string of short walks which make links between places with no real physical connection, and as many portraits of inhabitants of these Paris suburbs, whose urban features are forever changing. The sociological, cultural, economic and political challenges with which we are usually confronted where suburbs are concerned are present between the lines, so to speak, but there is no question of putting them centre stage; on the contrary, they are left, as it were, in mid-air, making way for poetic and unexpected words and representations.

In this four-handed work, the issue of the other is developed in several directions, starting with the collaboration between the two artists: “When our worlds met, a third world was created, one which belongs neither to her nor to me”, Roeskens suggests. 5 Despite the film’s own existence and its autonomous circulation in the form of screenings, it was initially shown in the context of a broader exhibition arrangement, alongside visual cartographic work displayed on the actual walls, floor and ceiling of the Khiasma space, echoing the cartographic approach which guided the film’s process. Another shorter film also exists, like a kind of “bonus”: in Notes filmiques de bas de page (tectonique), Roeskens records Marie Bouts’s hand re-drawing the maps of the strolls which go to make up Un Archipel. So this collaborative work is essentially off-centered and dispersed, struggling to make do with a single perspective forming the main film; it proposes ramifications and byways which echo those passages, detours and shortcuts which the artists sought through their exploration. Figures of the other proliferate through the different participants with whom the artists worked within variable time-frames. These portraits taken all together emphasize the artists’ wish to show a heterogeneous community, mixing not only different cultural origins but also very distinct age categories. The film project is not based on the political challenge of representing an eclectic community; on the contrary, the artists acknowledge the difficulty raised for them by the desire to work with other people, and getting them to share their common imagination starting out from a praxis of song which has no foothold in the social and cultural reality of the Ile-de-France—the Paris region. “It has a very fictitious aspect, and it is in this sense that what we have come up with is more of a fiction than a documentary. I think that it’s in this place that you may get the sensation of a ghostlike community, and a feeling of melancholy: the dream of the community which sings its territory has no place in reality. What is more, this is not an initiative involving everyone, it is a project produced by two people. In the end of the day, it has nothing to do with minorities and ethnic communities. But what does exist in the film is an imaginary space, which several people have helped to build.” 6

It is also through his passion for music, where baroque music meets traditional music coming from South America, that the artist Nino Laisné addresses spectators and shares his experience of otherness. His film En présence (piedad silenciosa) (2013) opens with a stage-like space: Vincenzo Capezzuto sings a Venezuelan tonada accompanied by the musicians Pablo Zapico, playing baroque guitar, and his brother Daniel Zapico, playing the theorbo. The singer’s ambiguous voice has a spellbinding dimension and seems as if disconnected from the body which develops it. His androgynous aspect enables the viewer to make an imaginary comparison with the young woman whose song describes her unexpected pregnancy. The musical performance is filmed like a classical concert: this image itself is disturbing, at first glance very polished, but it is transformed just when the camera moves to take a reverse shot over the empty seats of the spectators. The camera then slides into a space which surveys the stage, and dwells on a woman who finds herself in the wings, observing the performance. Incarnated by Cécile Druet, an actress with whom Nino Laisné has worked on several occasions for photographic projects, she listens attentively to the song. The posture of her body, with her arms clutching documents against it, and the disturbed look in her eyes seem to signify her fear that someone may take her by surprise. Her clothes leave us in no doubt about her female identity, but her facial features have a disconcerting ambivalence about them, echoing the singer’s voice. The film, as a whole, increases the number of duplications (the hybrid character of the music recomposed by the artist and the twinned nature of the Zapico brothers are examples of this). The space of the open stage, awash in light, refers us to its opposite: the private space where we find the character incarnated by Cécile Druet, a space which eludes the assumed theatricality of the performance, and conjures up confusion and emotion. En présence (piedad silenciosa) is a surprising film, because the rigour and effectiveness of its system gradually allow a whole host of details to be developed, some of which call for an immersion in the musical performance and its complex field of references. The motifs of the double, hybridization and aporia or contradiction 7 appear like an unusual way of asserting the ‘queer’ dimension of its stance and its artistic and political sensibility. 8

In 2007, André Fortino made Traits d’union, a video in which he records a strange and politically incorrect family scene: a face-to-face talk with his father during which they snort some cocaine, thus giving rise to an exchange. Otherness, here, is taken against the grain: it is the physical resemblance between father and son which strikes us. The notion of authority is also shifted; father and son are accomplices in their offence: the father does not incarnate prohibition, rather he is the vehicle transmitting a trangressive ritual. Traits d’union appears like a programmatic work: this project emphasizes Fortino’s desire to turn his art project into an experimental arena verging on insult; a space in which there are ever more attempts to confront the body with an ordeal in a confrontation and a resistance with the norms of propriety. Sociability, subordination and “domestication” 9 are all challenges to which Fortino endlessly returns. In response to the social order to comply with established cultural and political codes (being a father, being a son, being an artist, being a man?), Fortino answers with a transformation which is recurrent in his oeuvre: he becomes that pig-man by sporting a mask to make different performances and videos. So he strolls about the city of Marseille in the dead of night (Night, 2010) and in the Art-O-Rama contemporary art fair (Art-O-Rama, 2009). The other, here, is the animal as a metaphor of a resistance to the sociability that is regarded as peculiar to the human being. This animal-in-the-making which Fortino presents and stages, through which he seems to gain access to a form of “savagery” is indeed peculiar to the human being in his desire and quest for a self-dispossession and resistance to the values of rationality, consumption, and performance. In 2009, Fortino illegally got into the old Hôtel-Dieu (general hospital) in Marseille, which was billed for destruction; he wore his pig’s head mask and, without any prior plan, set about exploring the premises. The record of that off-the-cuff performance shows a lengthy and violent struggle with all the component parts of that place which had been abandoned: its architecture, its furnishings, and a large number of objects and pieces of equipment that were reminders of the place’s medical functions. Fortino underscored the basic nature of that action at the old hospital in the development of his praxis: the state of trance which he managed to sink into, the freedom he gave himself in the development of his gestures, and the serenity he felt after that performance all triggered an inventorial repertory of his work as a performer, prompting him to devise two other projects that followed in the immediate wake of Hôtel-Dieu. Les Paradis Sauvages (2013), in collaboration with Hadrien Bels, was thus presented as an initial duplication in which Fortino rekindled each one of the scenes in Hôtel-Dieu in new places, choreographing them with great precision so that they worked like a mirror of the initial performance. He no longer wore a mask; the challenge henceforth seemed to involve imagining the gestures and actions made in the state of altered consciousness tried out in Marseille with a critical remove, and appropriating the forms produced by improvisation. The last part of the trilogy, a performance made for video and titled Le corps des formes (2015), reverted to a unity of place in a space which looked like a dance studio, where only the dark floor was lit up. In this way, Fortino became involved in a quite different relation to theatricality, adopting the codes of a contemporary dance performance in total contrast with his earlier experiments. A new relation to otherness mingled here with the relation between objects and the human body. The duality between subject and object here assumed an essential place and in different ways echoed the questions raised by the medically treated body—analyzed, opened, dissected, skinned—at issue in the context of a former hospital. It is perhaps in this latest work produced in collaboration with the choreographer Katharina Christl that we are confronted with a critical de-construction of the power of the artist’s male and athletic body; a body whose control and skills are re-adopted in the incarnation of inanimate things.

Mickael Phelippeau uses the term “bi-portrait” to highlight his way of including himself in the portrait of another. So the viewer has two portraits in front of him, which echo one another: the artist is simultaneously in two spaces, behind and in front of the camera, at once director and performer. Bi-portrait thus appears like a way of going towards another, or feeling the difference, but it is also part of the quest for a resemblance; Phelippeau is looking for something of himself in the other. In 2008, further to his meeting with Jean-Yves Robert, a priest at Bègles in the Gironde, Mickael Phelippeau developed an initial bi-portrait which gave rise to a choreographic work. 10 The piece started with a video (Jean-Yves, 2008, 11 min.) in which the figure of Jean-Yves Robert is only visible from behind through a sequence of photographs set in motion by the sound of the filming, and in rare static shots. This introduction shows a figure escaping from the label which gives him his ecclesiastical function: he is a priest, among many other things. Art, and stagecraft in particular, already had their place in Jean-Yves Robert’s life, as a spectator’s personal interest and as a work tool in the educational context, but the collaboration he became involved in with Phelippeau shifted his involvement in art very close to his body and to the hub of his daily life. The choreographic work starts on the floor and gradually develops in a vertical sense, leaving a major role to lines spoken and exchanges on stage. “These bodies are facts of culture. Wittingly included in a representation, they develop a tremendous potential in terms of auto-fictional performance. And merry encounter.” 11 Although we know that the capacity to construct a fictional character, and have the experience of a space and a time that are outside the daily round, are elements peculiar to performance, the above-quoted words of Gérard Mayen stress the opportunity represented by the stage space for experiencing other relations to oneself and to the public being addressed. The twosome formed by Mickael Phelippeau and Jean-Yves Robert in bi-portrait Jean-Yves describes a fundamental displacement, another way of living in your body, speaking, and trying out other systems of representation and signification.

In bi-portrait Yves C. (2008), Phelippeau became involved in a new collaborative experience, this time with the choreographer Yves Calvez. The challenges of joint work were quite different here, based on an exchange between two kinds of dance practice. In this second choreographic bi-portrait, Phelippeau wondered how a work for two could refer, both literally and figuratively, to the minority-based dimension of dance. He was interested in the traditional round dance practiced by Calvez, and more especially in a certain state of trance which it helped its performer to end up in. This dialogue between Phelippeau and Calvez shed light on an important dimension of the bi-portrait approach imagined by the choreographer, the dimension of an approach to otherness as a space in which to go beyond yourself, and become transformed. Bi-portrait Yves C. is based on the contact between bodies which lies at the centre of the round dance, and is developed from a series of figures of hand-to-hand encounters, interweavings, and portés, based on which the duo develops a choreographic vocabulary resulting from the exchange and mixing of their praxes.

Last of all, I want to associate the work and method of the artist Emilie Perotto with the issue of otherness imagined in this essay. I have been exercised by the term “sculptural situation” which she uses to define her sculptural praxis. The term ‘situation’ is often used in the field of performance, and in particular in the context of so-called participatory approaches, within which artists have tried to question the viewer’s role. In Emilie Perotto’s work, the “sculptural situation” refers us to the dynamics of the relations which link the artist, her work, and the spectators. In a discussion with the artist, we talked about the pivotal stage in her sculptural praxis represented by her 2010 residency at the Mont Châtelet Professional College at Varzy, specializing in wrought-iron craft. Quite used to doing everything on her own in her studio, and not delegating any production process to anyone else, Perotto was confronted, in that educational setting, with a world and a set of technical skills which were alien to her. This experience of reflection and collective production has encouraged a shift and given rise to questions about the distribution of skills and the artistic signature. This questioning of her praxis has prompted Perotto to distinguish different types of processes, such as delegation, collective production and joint creation. In 2015, during a residency at the Richebois Centre of Professional Rehabilitation in Marseille, Emile Perotto worked with different participants 12 to collectively produce the work known as Le Foyer 13(2014-15). “Each bit of polystyrene covered with mortar or chalk is passed from hand to hand to be worked. Without any pre-established organization, everyone clearly found their place, used their skills, and learnt from the others. Our foyer (literally, hearth or centre) tangibly celebrates our shared time together.” 14 During that same residency, she also developed other works which do not share the same collective status, such as Lucienne, Marc, Mathias, Marc, Lucienne (2015) 15, a series of cast aluminium bases which take the form of tree trunks.

The issue of doing things together is in no way something obvious; what is involved here is a stance gradually developed by the artist during her experiments in the context of different residencies, bringing in techniques and specific human situations. These experiments have played a predominant part in calling into question solitary and self-sufficient work carried out in the studio, encouraging Emilie Perotto to have recourse to other forms of know-how than her own, with an interest in a legacy which underscores the choice made by artists to completely abandon the direct action of the hand on matter, and prefer production processes which follow industrial models—here we might mention Donald Judd as an example. Today, Emilie Perotto is raising questions about new forms of collaboration by working with other artists. She has accordingly recently worked alongside Stéphanie Cherpin in a studio in Glasgow. This shared method puts her approach to sculpture as a “situation” back in the foreground, regarding sculpture as a “state of encounter” in the work and production process, but without questioning the autonomy of sculpture as an object. In this context, artists have been concerned with calling into question the way each one goes about things in order to make things together in different ways. Back in the 1950s, in New York, the artist Sturtevant had both relevantly and radically questioned this capacity to get to the heart of an art praxis, to the point of thoroughly mastering the work processes of someone like Andy Warhol, Frank Stella or Jasper Johns. She had brilliantly understood that art was not a matter of visual signature, and style, but rather of a complex conceptual task involving far more than resemblance.

Circulating among works is an invitation to seek out all the spaces and all the experiences still available today, through which we can sense otherness in its many different facets, and let it proliferate. The artists looked at here all unusually address their relations to the figure of the other from the viewpoint of representations (the multiplicity of portrait forms) and creative processes bringing in performers, participants, and other artists. A common dimension seems to emerge from this stroll: the ethical and political need to re-think our capacity to exchange, share, and make ourselves available for human relations and experiences outside established settings.

Michel de Certeau, whose words I have quoted at the beginning of this essay, has cast a critical eye over the condition of the historian’s praxis. He writes:

“To be sure, he, too, has received from society an exorcist’s task. He is asked to get rid of the danger of the other. He is part of those societies (including our own) which Lévi-Strauss describes by anthropemia (from emein, to vomit) by contrasting them with cannibalistic societies: the latter, he says, see in the absorption of certain individuals, in possession of fearsome strengths, the only way of neutralizing these latter and even using them to advantage. On the other hand, our societies have chosen the opposite solution, consisting in driving these fearsome beings out of the social corpus, by keeping them temporarily or permanently isolated…in establishments designed to that end.” 16

Certeau sought forms of otherness everywhere, and in particular in art and literature, because, for him, they represented the most fundamental safeguard against the subordination of people, the impoverishment of cultures, and standardization of thinking, and all the authoritarian and sectarian aberrations which are also still proliferating.

Vanessa Desclaux, May 2016

Footnotes :

1 Michel de Certeau, L’invention du quotidien, 1. Arts de faire, Gallimard, 1990, p. 217.

2 I have borrowed these terms from Flavie Pinatel, when she talked about her film Ramallah in an interview with Judith Mayer.

3 A voice-over which whispers at the beginning of the film.

4 Till Roeskens in an interview with Olivier Marboeuf.

5 Ibid.

6 Marie Bouts in an interview with Olivier Marboeuf

7 Something may be one thing and another thing, which nevertheless seem incompatible; it is not possible to decide which, it is both at once.

8 This ‘queer’ character is decisively asserted in one of the artist’s most recent projects, a performance which stages the performer (dancer, choreographer) François Chaignaud in a new exploration of the traditional Spanish song titled Tarara, which is the name of the female character of ambiguous sexuality, whose story it tells.

9 In 2013, Fortino presented a performance with three other performers titled La domestication n’aura pas lieu. This performance, which was given at the IAC in Villeurbanne for the exhibition Rendez-Vous 13, presents four people practicing Simhâsana, a traditional yoga position known as the lion position, whose beneficial effects are considered to be many and varied from the viewpoint of the psyche and physical energy.

10 The bi-portraits project began in 2004 with a series of photographs.

11 Gérard Mayen, “Extrême-ouest contemporain – Lorsque la Bretagne danse”, www.mouvement.net, 25 September 2008.

12 With “Franck, Franck, Maguette, Malek, Frédéric, Marie-Luce, Karine, Emilie, José, Kader.”

13 Materials used: polystyrene, chicken wire, mortar, concrete, chalk, dyes, ridgepoles, bicycle wheel, dimension 300 x 450 x 55 cm.

14 Words of Emilie Perotto about the work foyer.

15 Materials: five aluminium casts, dimensions variable.

16 Michel de Certeau, “les figures de l’autre”, La possession de Loudun, Folio, p.327-8.

Picture taken from the film - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Picture taken from the film - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Picture taken from the film - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Picture taken from the film - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Picture taken from the film - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Picture taken from the film - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Picture taken from the film - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Picture taken from the film - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Picture taken from the film - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE - © Guillaume Gattier

Picture taken from the film - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Picture taken from the film - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Picture taken from the film - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE - © Aldo Abbinante

Picture taken from the film - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Polystyrol, chicken wire, mortar, concrete, lime, dyes, ridge, bicycle wheel, 300 x 450 x 55 cm

5 aluminium casts, various dimentions

Video, 14'

Video, 8'

Video, 37'

Video, 9'44"

Video, 8'

Video, 3'15"

Video, 5'43"

Video, 5'47"

Video, 45'

Video, 45'

Video, 45'

Video