From one stage to the next

Tuck Pendleton, a brilliant but ill-disciplined test pilot, is the guinea-pig for a top secret miniaturization project to dispatch him on board a capsule to explore a rabbit’s organism. But nothing happens as planned in this Aventure intérieure [Innerspace] directed by Joe Dante (1987), for, in the wake of an unexpected operation by a gang of terrorists and after a classic car chase, the hapless Pendleton finds himself propelled into the body of Jack Putter, a hypochondriac, angst-ridden supermarket check-out operator. Not knowing where he is, the character played by Dennis Quaid is connected through probes to his host’s systems of hearing and sight, and starts communicating with him. What interests us here in this adventure film is this precise moment when one body comes into contact with another body and traces the premises and possibilities of a shared experience that is both tense and offers no guarantee of success (the film does end well, nonetheless). What kind of encounter “outside” might this be, in the tangible world of our social and perceptive frameworks? How can an artist try and hook up to our sensitive organs, and occupy the body as a medium,1, but without establishing an authoritarian situation?

Experience is a notion that is hard to define and put into words. It seems more than ever to be hackneyed, retrieved from scratch to sell insurance, a car, a mobile phone or a night-cap supposed to guarantee us a “revolution” in all security. This, paradoxically, is what makes it indispensable today: the absolute need to re-use it so as not to let advertising, the ever faster circulation of information and news, certain Internet shortcomings and our navel-gazing make us “poorer in remarkable stories”.2 Experience is not given as such, but involves the liaison and negotiation between one or more bodies, an environment, a situation, a circumstance.3 Otherwise put, to borrow words of Georges Bataille, “what matters is not the utterance of the wind, it’s the wind”.4

If all artworks can be the subject of a special experience, we will not dwell here on a set of praxes associated with performance, clearly introducing these questions by the direct and solicited involvement of a “living and feeling body”.5 Widely incorporated today by the art institution, not to say ubiquitous, performance, in a nutshell, tallies with a diverse range of forms involving concerts, lectures, dance, sculpture, poetry and, more broadly, body, word and sound. This essay offers an opportunity to make a short and selective tour of works of artists associated with the ‘live’ issue, introducing a certain joint presence between performer and viewer.

Frameworks of experience

The ‘live’ idea intuitively echoes the idea of the spectacle—with which performance seems to be in perpetual (re)negotiation—and the stage on which it unfolds. Whatever this latter’s format and material form, it delimits a spatial and symbolic distribution between performer and audience. In imagining social life as a stage, the American sociologist Erving Goffman made the analysis that our ordinary experience is defined and organized by a set of “frames” which enable us to understand what is happening in a given situation, and help us to react to it.6 However, these frames may be the object of “transformations” which introduce new data in the game rules and partly reconfigure his stakes.

Nicolas Floc’h’s Structure multifunctions (2000-2007) is not strictly speaking a stage, or, to put it otherwise, it is not—potentially—just that. It is in fact entrusted to visual artists, musicians, dancers, and cultural institutions which will autonomously determine, through the association of the different modular elements which compose it, the function and the form to be attributed to it: a décor that can be handled and moved in the work of the choreographers Rachid Ouramdane and Christian Rizzo (FRAC Champage-Ardenne, 2001), a stage maltreated by the heels of a flamenco dancer in the work of Inaki Bonnillas (Programm-Art Centre, Mexico City, 2003), a concert set for the Tarwater group (Klapstuk 12 International Dance Festival Leuven, 2005), but also a bar, research laboratory or an area dedicated to lectures. Devised by the artist as an open score to be interpreted, the work represents the starting point for a project and determines a specific use at the same time as each occurrence offers it a chance to re-invent itself. 7

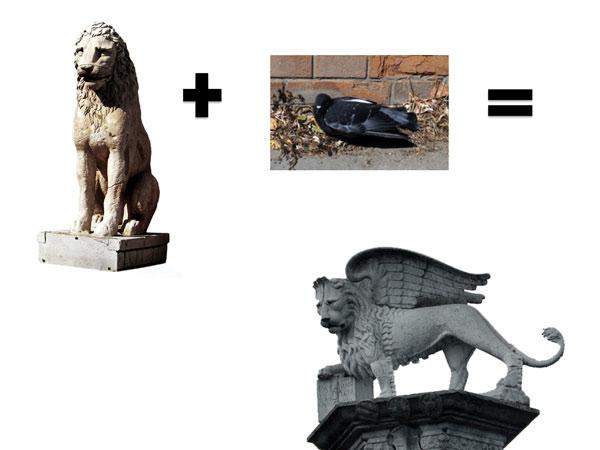

This possibility of producing a diverse range of propositions based on one and the same medium calls to mind Three Evenings on a Revolving Stage, orchestrated by Jean Dupuy at Judson Church between January 8th and 10th 1976. The French artist had by then been living in New York for almost ten years. In 1972 he devoted himself to the organization of collective events in his apartment and places which became emblematic, like The Kitchen. For those three evenings, Jean Dupuy set up a rotating circular stage in the middle of a church and invited 18 artists8 to come up with a 5-minute performance about or based on this element, while the audience sat all around. If Jean Dupuy’s structure did not comply with modular criteria like Nicolas Floc’h’s work, it still steered the various projects proposed. By way of example, Nam June Paik duplicated the gyrating character by positioning a turntable with a handle on which listening to 78 rpm records was altered by drops in intensity due to the way it worked, and by means of the artist’s not very careful manipulations. Sitting on a chair and revolving on his own axis, Jean Dupuy for his part produced a mayonnaise to a background of Maoist songs—nothing less than a summary of the revolution wittily executed. He thus declared: “I didn’t really give the artists themes, but restrictions (time, space, sometimes even the medium...). A frame. I applied this equation “title = constraint” to all the collective performances I organized.”9

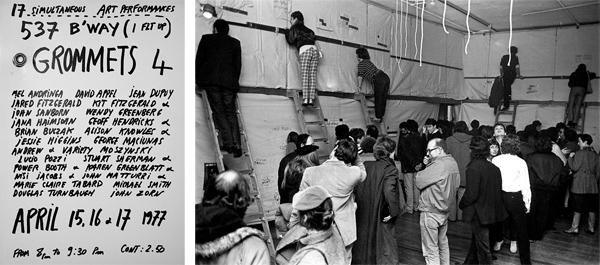

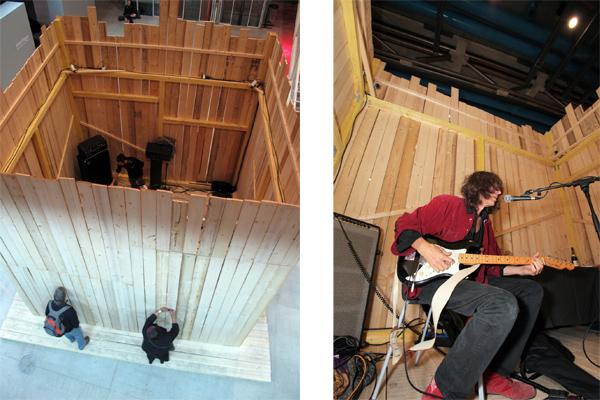

Between 1976 and 1980, Jean Dupuy organized several evenings in his apartment which were called Grommets, during which spectators discovered the performances through a hole made in fabrics hung from floor to ceiling. This game of distance and voyeuristic expectation was in a way extended in the installation In My Room which Arnaud Maguet presented in 2011 on level -1 at the Centre Pompidou.10 This was a cubic space bounded by high walls made of shuttering timber, banning access—physical and visual alike.11 The title borrows that of a Beach Boys’ song and plays the card of the teenager’s room where the world arrives, and, which, thanks to the Internet, the teenager has no need to leave. Between the wooden slats, you can make out an assortment of instruments, wires and consoles, as well the musicians, performers and authors invited to intervene out of sight—or almost, because the interventions are in reality re-transmitted live on a nearby screen by way of surveillance cameras. Apparently replacing the eye like an acousmatic device, the live experience is perverted twice over, even though operating in its own way, by being mediatized by a simultaneous broadcast.

Like so many expressions of the sculptural dimension of the stage, these different projects describe a framework of artistic production which is not only seen as a space but above all in terms of a scenario.

Technological vs. organic, acoustic perspectives

If Arnaud Maguet’s installation involves complex mechanisms of experience in the Internet age, Damien Marchal, for his part, tries to explore the performative and acoustic potential of a confrontation between the organic and the technological. By experimenting in particular with the use of peripheral computer devices, for the performance Hymnus in ioanem & western digital, presented at the Glasgow International Festival, the artist organizes the unlikely encounter between the Sirens of Titan choir and ten hard drives. During the event, the voices of 35 singers interact and are modulated on the basis of continuous frequencies emitted by the electrical apparatus, while at the same time moving about within the audience to propose a spatialized and evolving listening experience. The result is a series of sound layers which envelop the spectator.

Though in a quite different mode, this sedimentation recurs in Félicia Atkinson’s work, where improvisation and looping have an essential place, tending as they do to form “systems of appearance.”12 The painted and water-coloured bits of fabrics, cardboard boxes, rods and other gleaned materials which she spreads and organizes in space conjure up a pagan rite, and seem to trace contours of pending fictions. With a parallel praxis as a musician, her sound performances, made with the help of a synthesizer, a computer and pedals producing varied effects, are based on logical systems of repetitions and echoes which describe stretched and dreamlike landscapes, a contemplative area where the machine and the organic seem to dissolve, the better to re-invent the relation between the human body and its environment.

Click here to listen: Félicia Atkinson, L'oeil, from the album A ready made ceremony, Shelter Press, 2015.

The outside adventure

The works referred to thus far are part and parcel of contexts clearly dedicated to the artistic event, in the institutional settings of art, be they galleries, exhibitions or performance festivals. If the phenomenon is obviously not new and echoes a history inherited from the avant-gardes trying to merge art and life, a certain number of artists are still incorporating their actions within the public place. On this subject, David Zerbib notes that “the contemporary performance is being developed on a more local, micro-political scale, sometimes on the borderline of visibility. It is less a time for radical ,provocation than for the marginal transformation of a situation, capable of showing a perceptible dimension that has remained in the shadows, and reconstructing a possible circulation or making it possible to perceive, through its plasticity, the appropriation potential of a space.”13

So in 1982 Julien Blaine tumbled down the monumental stairway at St. Charles station in Marseille, as part of the filmed performance Chute-Chut!, involving his own body and endangering it. Once he reached the bottom, he made a “chut/sssh” gesture with his hand, in an upheaval of language typical of his art praxis. Olivier Crouzel, for his part, is interested in the anonymous performers of the daily round, who, each in their own way, “perform” in the urban space, often without us paying any attention to them. As part of a project in progress, he goes to meet street musicians, filming them and recording while they play. The images obtained are then projected onto building facades, while the sound, which tends to become confused with surrounding noises, is broadcast in another place. The artist thus restores a visibility and a presence—here become monumental—to these musicians who, most of the time, we hear without seeing.

These examples, through their furtiveness and the particular relation they introduce in relation to witnesses—more than spectators—of the scene, incidentally raise the inevitable question of the accessibility and conservation of such interventions, henceforth involving documentation or video mediation, be it photographic or digital.

Lecturer and storyteller, words

Last of all, let us dwell on two unusual figures associated with oral transmission and the circulation of knowledge. The first, who has enjoyed a marked revival of interest in these last few years, is that of the lecturer, with certain artists appropriating his/her attributes and the systems used by this figure the better to shift them to other terrains. Bettina Hutschek thus produces readings-cum-performances, complete with obligatory slide shows, during which she recounts the history of a city (Bucharest, Venice, Brest or New York) in the form of tales mixing observations and real facts on the one hand, and, on the other, fictitious elements which are part of a personal mythicization of these great cities. In 2003, Yves Chaudouët, for his part, proposed a performance titled WAWGWAWD?, taken from a video made a few years earlier. In it he staged a lecture developed by John Cage in 1961 to answer questions raised by his students; “Where are we going? And what are we doing?”. It was conceived as a polyphonic score for four readers, with the voices of each performer—and the autonomous discourses they underpinned—superposed on each other to compose “a tempting structure, in the chaos of simultaneous babble, a form of translating the movement of thought, its contradictory adjacencies, and the futility of its transcription in an intelligible form.”14

During his residency at the Villa Kujoyama in Kyoto in 2012, Le Gentil Garçon produced the video Chronique du monde d’avant in which an 81-year-old storyteller, abiding by the Kamishibai tradition (a sort of travelling theatre), describes to his audience a time when man did not have the means to put the world in peril. What is involved here is encounter, between the speaker’s body and those listening, by way of a narrative which turns out to stem from morality and raise ethical issues, but does not include or impose any explanation. For Walter Benjamin, the storyteller’s whole art resides in his “ability to exchange experiences”.15 As a stratification of memories and interpretations, his narrative becomes the witness and the object of a circulation, of a possible re-appropriation and transmission on the part of the listener.

In our contemporary society, has experience become less “communicable”, 16, as Benjamin worried about back in 1936? The question is a complex one, and certainly needs re-appraising in the age of the Internet and new technologies, but the fact remains that a certain number of artists are trying to apply a diverse range of situations and scenarios, each time re-enacted and shifted in relation to contexts and “participants”, putting the body and the fragile energy of the live show, presence and interpretation, at the heart of their praxes—and this on both sides of the stage. In ways which differ markedly from a relational and participatory art, these contact zones, perhaps better defined as transfer zones, represent the ferment of a plural expression capable of being put back in motion and into words.

Raphaël Brunel

Translated by Simon Pleasance

Author's note

This essay was gradually established from the exploration - and in some cases from the discovery - of artists works presented by Réseau documents d'artistes, that its necessarily selective transcription attempts to connect differents practices and works in their diversity.

Otherwise some of its stakes are in line with a researches ensemble run in collaboration with Anne-Lou Vicente following the contemporary art journal about sound VOLUME.

Bibliography and external links:

1. David Zerbib, “Richard Shusterman : les effets de la philosophie douce “, Le Monde des livres, 29 November 2007.

2. Walter Benjamin, “Le Conteur”, Œuvres III, Paris, Folio Essais, Gallimard, 1970, p. 123.

3. See John Dewey, L'art comme expérience, Paris, Folio Essais, Gallimard, 2010 / Art as Experience, Perigee Books, 2005.

4. George Bataille, L'expérience intérieure, Tel, Gallimard, 1978, p. 29-30.

5. See Richard Shusterman, Conscience du corps. Pour une soma-esthétique, Paris, Éclat, 2007 / Body Consciousness: A Philosophy of Mindfulness and Somaesthetics, Cambridge University Press, 2008.

6. Erving Goffman, Les Cadres de l'expérience, Paris, Le Sens commun, Minuit, 1991 / Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience, Northeastern University Press, 1986.

7. Since the work was acquired by the Fonds national d'art contemporain [FNAC] in 2007, the activations correspond to the different propositions of the exhibition curators for interpreting and re-enacting the archives associated with the piece.

8. Vito Acconci, Olga Adorno, Jean Dupuy, Simone Forti, Philippe Glass, Jon Gibson, Jana Haimsohn, Julia Heyward, Hisachika T, Nancy Lewis, Michael Krugman, Mabou Mines, Nam June Paik, Ricard Peck, Charlemagne Palestine, Peter Van Riper, Richard Serra, Ven. Sherab, Nancy Topf.

9. Interview with Éric Mangion in Jean Dupuy, À la bonne heure !, Semiose éditions / Villa Tamaris Centre d'Art / Villa Arson, Nice, 2008.

10. There was also a question of revolution and allusion to vinyl because the installation was part of a solo show of the artist’s work titled “33 revolutions per minute”.

11. The roof was nevertheless left open, enabling people on the upper level in the Centre Pompidou forum to more or less make out what was happening.

12. Laurent Courtens, “ll y aura peut-être une harpe... “, L'Art même, n°59, June 2013.

13. Interview with David Zerbib, “ Interroger l'art à partir de ses marges”, Stradda, n°19, January 2001, p. 46.

14. François Piron, “Postface” in Où allons-nous ? Et que faisons-nous ?, Arles, Actes Sud, 2003.

15. Walter Benjamin, op.cit., p. 115.

16. Ibid, p. 129.

Rachid Ouramdane, Christian Rizzo, mai, 2001. Frac Champagne-Ardenne, Reims, Intervention / performance : Rachid Ouramdane, Christian Rizzo (choreographers), Nicolas Floc'h. Length 45'.

Inaki Bonillas, Casilda Madrazo, mars 2003, Program-Art Center, Mexico City.

Tarwater, Klapstuk 12 International Dance Festival Leuven.

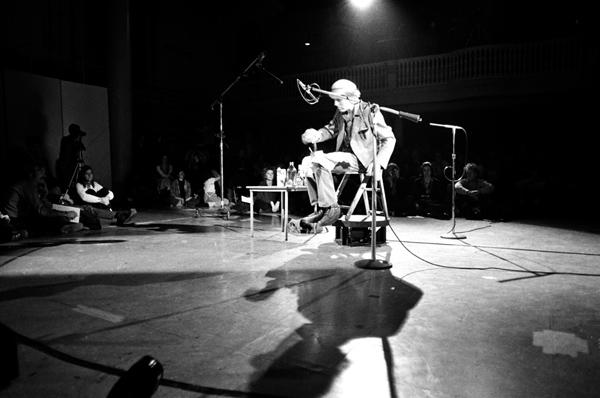

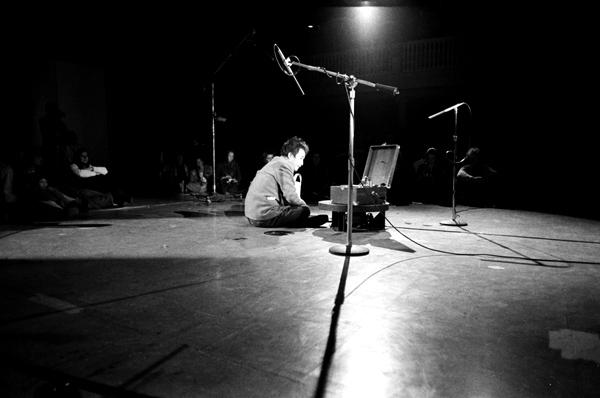

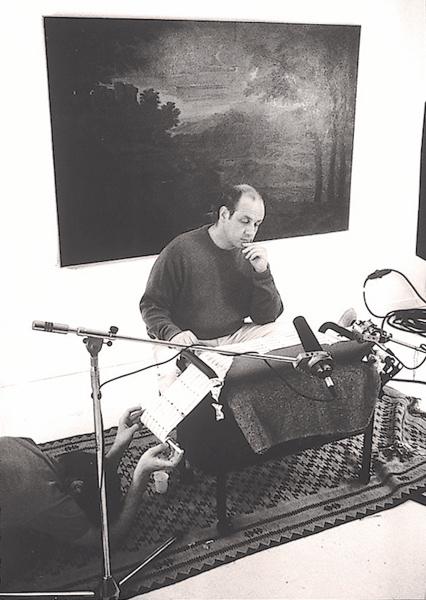

Performance of Jean Dupuy as part of "Three Evenings on a Revolving Stage", January 1976, New York.

Performance of Nam June Paik as part of "Three Evenings on a Revolving Stage", January 1976, New York. - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Left : Jean Dupuy, poster of Grommets' evening #4, 51 x 36,5 cm, April 1977.

Right : 5th edition of the "Grommets" evenings.

Wood, surveillance cameras, video projection and performances, 400 x 500 x 500 cm (structure).

Courtesy Galerie Sultana, Paris.

Wood, surveillance cameras, video projection and performances, 400 x 500 x 500 cm (structure).

Courtesy Galerie Sultana, Paris.

Wood, surveillance cameras, video projection and performances, 400 x 500 x 500 cm (structure).

Courtesy Galerie Sultana, Paris.

Sonic action for 1 choir / 12 hard drives, length: 27 min, With the collaboration of Peter Shand, choir-master, and the Sirens of Titan choir. Glasgow International Festival, Social Landscape, Creative Residency: Trongate 103 and WASPS, length 3 months, Glasgow, 2010. Photo : Patricia Fleming.

Solo show at Land and Sea, Oakland, 2015.

In-situ sculpture, ink on silk papers, PVC papers, pottery, clay, second-hand book, liquid ink, 240 x 280 x 10 cm. View of L’attraction Minérale, group show, Lieu Commun, Toulouse, 2013.

CHUTE-CHUT !, (MONUMENTAL STAIRS OF ST CHARLES STATION) , 1982Pictures taken from the film.

WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Video installations. Videos of musicians on city buildings and in nature. Local sound system.

WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Performance-Reading with the help of a Power Point presentation.

View during the performance at Art-O-Rama, Marseille, 2008.

Performance-Reading, ca. 30 min (screenshot from the video).

WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Adaptation and set design based on Où allons-nous ? Que faisons-nous ? . Performances at the Rencontres internationales de la Photographie in Arles, at the Frac Champagne-Ardenne, at the CapcMusée in Bordeaux, and at theThéâtre Dijon Bourgogne-CDN... Written and directed by: Yves Chaudouët / General production: Ludivine Reynier / Actors : Yves Arcaix, Pierre François Doireau, Medhi Lecourt, Laurent Poitrenaux and Antoine Romana. - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Video, 10'42 min - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Video, 10'42 min - WATCH THE FILM AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE

Performance de Nam June Paik.L'artiste joue ou maltraite des 78 tours sur un tourne-disque à manivelle.

Vidéo, 2’38’

Vidéo, 2’08’’

Extrait vidéo de 3’39’’

Extrait vidéo, 5’25’’

Vidéo, 10’42’’