I am a name without a title: Thoughts on impossible identity

"I am a name without a title,

patient in a country where everything

lives in a whirlpool of anger.

My roots

took hold before the birth of time,

before the burgeoning of the ages,

before cypress and olive trees,

before the proliferation of weeds"

Mahmoud Darwich, "Identity card"1

Identity is a challenging mystery to unravel. Rebellious, it won’t sit still for the painter. In perpetual motion, forever transiting through times and spaces on its course, bodies it inhabits, stories it builds, it’s a so-called chameleon that might more aptly be termed poetry.

For meaning to pass from sender to receiver, semiotics suggests relying on signs arranged in a special order: these are the vectors transmitting meaning and message, riddle and answer…But should we by relying on signs for a message that refuses all bounds? The word identity does not suffice; its discursivity defies discourse. Spell it out in letters, render it in sound or image, it will always refuse to be reduced, though countless the hands keen to grasp it.

Where semiotics fails, art steps in. Inventing their own signs, languages and stratagems, the artists we look at here open up worlds to encompass the many facets of identity, which in truth is always plural, worse still, impossible. These artists look into the mirror meant to reflect identity and shatter it. They then go out to retrieve its fragments scattered to far corners of the visible and invisible. Ymane Fakhir (1969–), Gabrielle Manglou (1971–), Leïla Payet (1983–) and Moussa Sarr (1984–) fit these fragments together in another order, taking us from evident to concealed in a quest and through the labyrinth.

At the beginning of his career as a performer, Moussa Sarr began with the evident. He muses on being the sole person of color raised between two continents in Corsica. Joking just to get by, his performances enquire into signs used by others to define his body, and through it, his very being, with monkey cries, blundering and animal movements. Touching the most elementary levels of racism and absurdity, this catalogue is the subject of his early works, imitating others imitating him and neutralizing any attempt at reduction. Can a person of color put on blackface? What hides behind the monstruous red lips of Banania? (Blackface, performance, 2019). The literal, provocative side of Sarr is more complex than it might seem, with a flip slide mobilizing impossible words, the myth of Narcissus, and his own death (La Grande Dévoreuse, performance, 2018), which is followed by rebirth (Narcisse metamorphosis _The Peacock, performance, 2018). Tired of portrayal by others, the artist transforms himself into myth. Performing at the Villa Médicis, the audience attends his funeral and his rebirth as a peacock guided by Narcissus, better to communicate in Pelistics, a language the artist invented for the curious to finally understand each another beyond language, words, meaning and signs. Sarr’s strategy is self-centered in the interest of the collective. It is rooted, so to speak, in the same earth that gave rise to Rousseau’s thought, a few centuries back, at the start of Confessions: “Myself alone. I feel my heart and I know men.”2 “I” is the filter through which we apprehend the world. If I know myself, I know others, and vice versa. Combining mental portraits drawn by the two parties allows them both (mine and that of my society) to appear at once. Through auto-fiction, Moussa Sarr combats cliché and all attempts to subjugate a being always on the move, one which too many Others are defining on behalf of an I.

Ymane Fakhir, on the other hand, is never seen in the photographs, video and installation work she co-creates. We find hands, feet, edges of the body, details of a haircut, gestures, postures, and objects (Un Ange Passe, 2003; Handmade, 2011-2012; Fête du Trône, 2009). Out of detail hidden in the whole, she investigates, collects and recounts to let singularity emerge. Make connections between beings and two shores of the same ocean; denounce abstractions trying to label types and norms, habits and constraints…The French-Moroccan artist returns from regular trips between Casablanca and Marseille bearing customs and habitus, traditions become one with bodies, practices become rules with no when or why. Using methods she proudly describes as indebted to Patrick Tosani, she isolates the form of a sound from the world around it, setting up the necessary distance for contemplating and recognizing legacy, which is always a construction, never natural. Fakhir collects archetypes and memories, immortalizing folklore, the persistence of images and traditions (particularly those of legacy in The Lion’s Share, 2019) within societies where people move at different speeds, a fact she discovered while collecting stories told by female immigrants who’d moved to what the artist describes as “an island.” For years, these women’s movements were limited to traveling between the native village they’d left and the transitional land they arrived in (As We Go along and Le Gouffre du Léopard, 2020). In the polyphony of collected voices and stories, where time comes to a stop as the journey begins, interstices start to appear. Into this gulf goes the artist, uncovering the sources of the social constructs that surround us, even if it means silencing individuals and communities. For the reclusive, for the exoticized and willingly invisible,for those we try to hide, she offers humble, discrete works of refuge, seeking to dig a way out of the impasse to which History and the majority of its writers all too-willingly consign the dominated, making great use of stereotype and other means of decontextualizing.

This good-willed, underhanded form of reparations also informs the work of Leïla Payet. For this artist, a different impasse presents itself from the start: the word “art” is not present in her mother tongue. The absence of the word, like the absence of her body in the West’s collective imaginary, and that of stories, social classes and the different cultures which have long surrounded her on her native island of La Réunion are an abyss into which deep diving easily risks drowning. It’s an abysmal paradox: how do you give form to the intangible, to the unnamable already incarnated in the living bodies all around you? In an almost didactic approach, Payet employs graphic signs and imaged symbols carrying a practice, objects of worship and symbolic representations. Images, slogans, and parts of stories overlay faces and trees, which the artist mixes in video (Discours sur le Colonialisme, Aimé Césaire, 3, series: “Tapis Mendiant,” 2014) on wallpaper and in human-scale photography (“LAMAILLAGE”, 2013-2014). Figures Payet photographs hide behind signs revealing them in fragments. Against a background of ornate textile, female models are photographed with a cross or a hamsa, Hindu calligraphy or Buddhist mantra (Spiritual Mix I and Bless You, from the series “LAMAILLAGE,” 2013-2014).

Poignant collective experiences take place in other projects by the artist. In 2021, at the academy where she conducted her studies, beside currently attending students, she contemplates the inner workings of the museum as institution and its mechanisms of promoting one form of art over another, success stories not trials, masters before apprentices…With students, she imagines a phantom museum in the form of an experimental, ephemeral storehouse, where works-in-progress are exhibited beside abandoned works, left in the school’s backyard, considered failures by their authors (Réserve des Horizons I3, 2021). Shown together, they come back to life for three days. They’re conserved, occasionally restored, and proudly exhibited, the better to experience how scrapped stories can exist. Does the institution play a role in defining the nebulous “identity”? If a response to the abstraction incarnated by the word exists, it should be pronounced collectively. For Payet, in rallying and coming together we’re able to articulate ways in which we might fill in the gaps of dominant narratives, add nuance to definitions and prevent reduction.

Gabrielle Manglou grew up on the same island as Payet, within the same collective history whose idea of unity she also defends. Contrasting Payet’s words and mediation, Manglou prefers riddles and rebuses. Hand-drawn lines link bowls set against a white background between seemingly ancient masks and a seascape with a lighthouse at its focal point. The story behind the labyrinthine work Frédéric Mitterrand et le Bol en Bois (2020) is quite funny. One might have offered the travelling French minister “traditional” bowls rather than these “mock works” by Gabrielle Manglou. Again, joking to get by faced with the preposterous, and hiding the seemingly self-evident are the artist’s strategies in reconciling with what too many have sought to make impermeable. No ocean is wide enough to swallow the shocks of history. In her installations, drawings, sculptures and sound work, she also hides in order to reveal the Other, or others, in every detail, from the obvious to the ridiculous and inscrutable. Even in their titles, her installations Amarrer à l’Ombre (2020), Délicatholitho (2021), and Catharsis et Clé de Douze (2012) are enigmas in which feathers and raffia stand beside lines of primary color normally associated with Western abstract art. Through mazes of small charms and touches of supposedly universal colors, the artist invites us to find a way out, through connections, and clearing new, unthought of, unnamed and heretofore invisible paths. By obscuring already abstruse discourse and figures, plunging into darkness and history, the artist shines a light across paths between worlds, essential beacons for mooring safely. Lines of rope and neon, seemingly sweet objects confectioned by the artist, cartoon-like forms, feathers and finery, cotton and cords, fake jewels and real sculpture are all mysteries waiting to be unraveled by anyone willing to take the time. Thus ever-present associations come to light: maps used by navigators at sea, but notably on land, through rum and chocolate brought back from the voyage for pleasure, with the blood that wrapped the gift washed off along the way. Suffering is rendered invisible far from home, but it never disappears. Everything leaves its trace. The artist collects these clues to unfold their every dimension.

Identity is artifice, illusion, a form of poetry. Its riddle has no answer, and that’s the key. To these semiotic abstractions, artists have responded with alternatives able to manifest the bodies and voices that the notion of identity made invisible, exposing its process of construction. Through subversion and subterfuge, strategy and counter-narrative, the art by which we arrive at our conclusion renders any attempt at definition—inevitably a reduction—obsolete. Nobody is born, everyone is in transformation. Into what? What History fed, what its interpretations shaped, what others projected, what I’ve chosen against all odds…Who am I in total chaos? There are no ready-made solutions to Pythia’s oracles. “Language and metaphor are not enough to restore place to a place,”4 Mahmoud Darwish observes. But in their plurality and poetry, they sketch lines and paths. To where? It’s always under construction.

"The stars had no role

But to

Teach me to read:

I have a language in the sky

And on earth, I have a language

Who am I

Who am I?”

Mahmoud Darwish, Poetic Steps 5

Notes :

1 Translated by Denys Johnson-Davis, Third World Resurgence, 2016

2 “Moi seul. Je sens mon cœur, et je connais les hommes.” Trans. Christopher Kelly, University Press of New England, Hanover, 1995

3 La Réserve des Horizons I, 2021, exhibition gallery for ESA Réunion, an ecosystem apparatus co-authored by Aesha Guillon, Nina Schrader, Thomas Nayagom, Ketty Damour, William pougary, Ravaonandrasana-Harmelle Jenny, Leila Payet, Amélie Morel

4 From Unfortunately, It Was Paradise, trans. M. Akash, C. Froche, & B. Maryland, University of California Press Books, 2001.

5 From Why Did You Leave The Horse Alone? tr. Mohammed Shaheen, Hesperus Press Limited, 2014

Translation: Elaine Krikorian

Un ange passe, 2003

Série de 14 images 60 x 90 cm

tirage argentique montage sous diasec

Handmade, 2011-2012

Ensemble de 5 videos en vidéoprojection

Vue de l’exposition A gorge sèche après la traversée, Bruxelles, 2017

Fête du trône, 2009

Travail en continu

Tirage Lamda, 120 x 120 cm

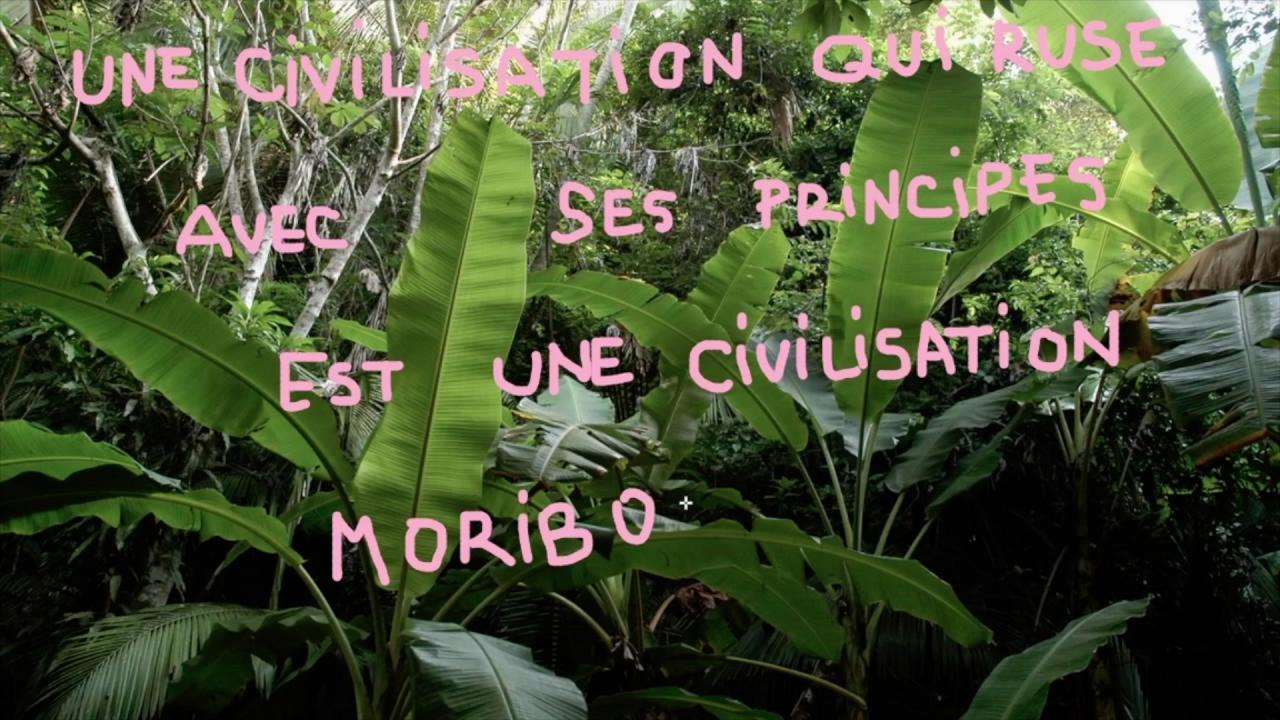

Discours sur le colonialisme, Aimé Césaire, 3

série « Tapis Mendiant », 2014

Citation vidéo, 48 s.

Créodalisque, 2013

Photographie numérique HD, dimensions variables.

Série Spiritual Mix I et Bless You

dans « LAMAILLAGE », 2013-2014

Fatima Bless U, 2013

Photographie numérique HD, dimensions variables

Série Bless U dans « LAMAILLAGE », 2013-2014

Frédéric Mitterand et le bol en bois, 2020

Dans le cadre d'une résidence de recherche à la Cité internationale des arts de la ville de Paris soutenu par la DAC Réunion et le FRAC Réunion.

Musique & sons : CORE duo artistique composé de Fabrice Laureau & Gabrielle Manglou

Flûte, effets, enregistrement & mixage : Fabrice Laureau

Voix : Gabrielle Manglou

© Adagp, Paris

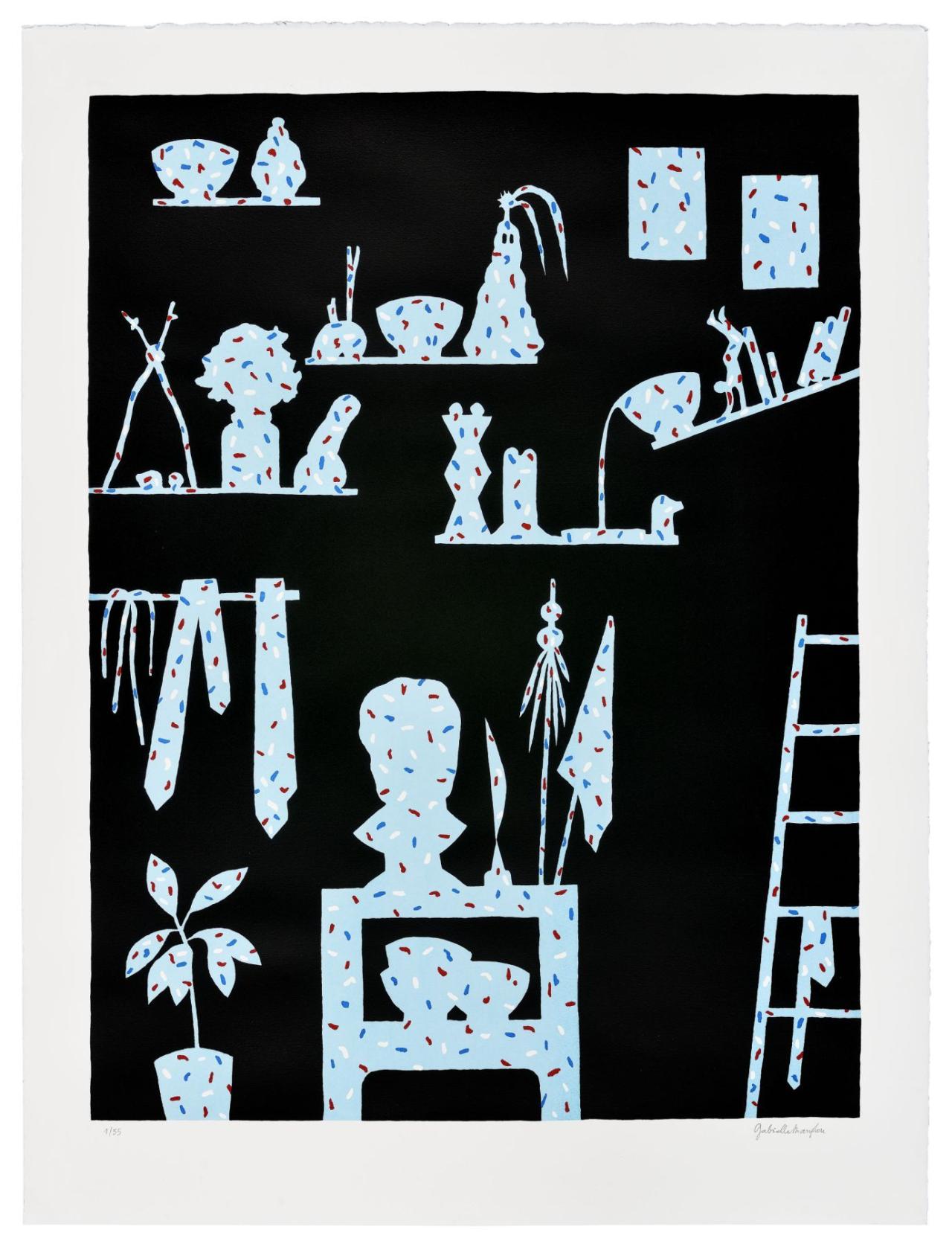

Des œuvres, des vraies ?, 2021

Estampe, sérigraphie

55 exemplaires numérotés

Collection CNAP

Commande d’estampe associant l’Adra et la Cité de la Bande dessinée dans le cadre de l’année de la bande dessinée - Institut sérigraphique, Séverine Bascouert

Amarrer à l’ombre, 2020

Vue de l'exposition, Musée de la Marine, Port-Louis, 2020

Photo : Marc Domage

© Adagp, Paris

Amarrer à l’ombre, 2020

Vues de l'exposition, Musée de la Marine, Port-Louis, 2020

Photo : Marc Domage

© Adagp, Paris

Délicatholitho, 2021

Vue de l'exposition au CAP Saint-Fons, Lyon, 2021

Photo : CAP Saint-Fons

© Adagp, Paris

Délicatholitho, 2021 [détail]

Vue de l'exposition Délicatolitho au CAP Saint-Fons, Lyon, 2021

Photo : CAP Saint-Fons, Lyon

© Adagp, Paris

Catharsis et clé de douze

Vue de l'installation à la Galerie des TEAT Réunion, Saint-Denis - La Réunion

Installation fabriquée à partir des restes des décors du théâtre

Photo : Gabrielle Manglou

© Adagp, Paris