Don't ever forget how precious you are

Countrysides may vary, yet many connect their first moments of freedom and roving, alone or with others, to a car. It’s no coincidence then that Johanna Cartier and Ben Saint-Maxent make use of cars in expressing the scars of youth.

Around a Citröen Saxo, Ben Saint-Maxent freezes time in a ride with friends, awakening the nostalgia of smoke-filled nights in the headlights. While parked, the car evokes memories of bromance, suggesting with open doors we might still hang out again. But between here and where we came from, at least one person is missing. Most-missed are those who didn’t have time to leave. By returning to live alongside the ones who never moved, Ben Saint-Maxent felt what he’d missed of the life he left behind. It’s a clean break. Writing is the beginning. It’s the script of scenes to come. In 2.0 epitaphs, Ben Saint-Maxent posts fragments of what might be called autobiographical fiction. There’s only a small step between word and image. The first time, it’s in a villa, reminding him of the abandoned house where they’d meet. He writes on the walls in her memory. Placed here and there individually, the story follows the path of a serie of sneakers, each fixed to the ground as if walking on tiptoes, their cavities holding flowers. In between these moments is a shop window—an opportunity to bring the street into the scene. It’s not the street the artist imagines from his village, the one he now lives on, but the street of a time in which the youth gets drunk on tiny bottles of nitrogen. This trilogy is perhaps the first chapter in his narrative. The next is to come, inspired by life, childhood friends, planting a garden and watching it grow.

If the landscape of Esterel mountains inspires poetry and romanticism in Ben Saint Maxent, Johanna Cartier is haunted by the “Disparues de l’Yonne.”1 Having fled the countryside and anxious about returning, the artist finds herself forced to face the past at the wheel of her car, a Citroën AX. Johanna changes hours into kilometers. She begins by filming her daily life and that of her brother, then looks into her background, asking into the causes and consequences of the status of social outcast.

Truly spending time in the field at sites she explores, the artist uses a sociological approach, drawing a map of emptiness and boredom, painting a portrait of an alternative France, one on the margins. Behind the veneer of pop art, or bling-bling, the installations conceal a critique of a classist and sexist society. Spotlighting these worlds, figures, and objects, she demolishes the clichés and prejudices that hold us back. With humor and affection, the artist incites expression and raises consciousness in both victim and offender, striving towards resilience. In the words of Emma Goldman, “before we can forgive one another, we have to understand one another.”

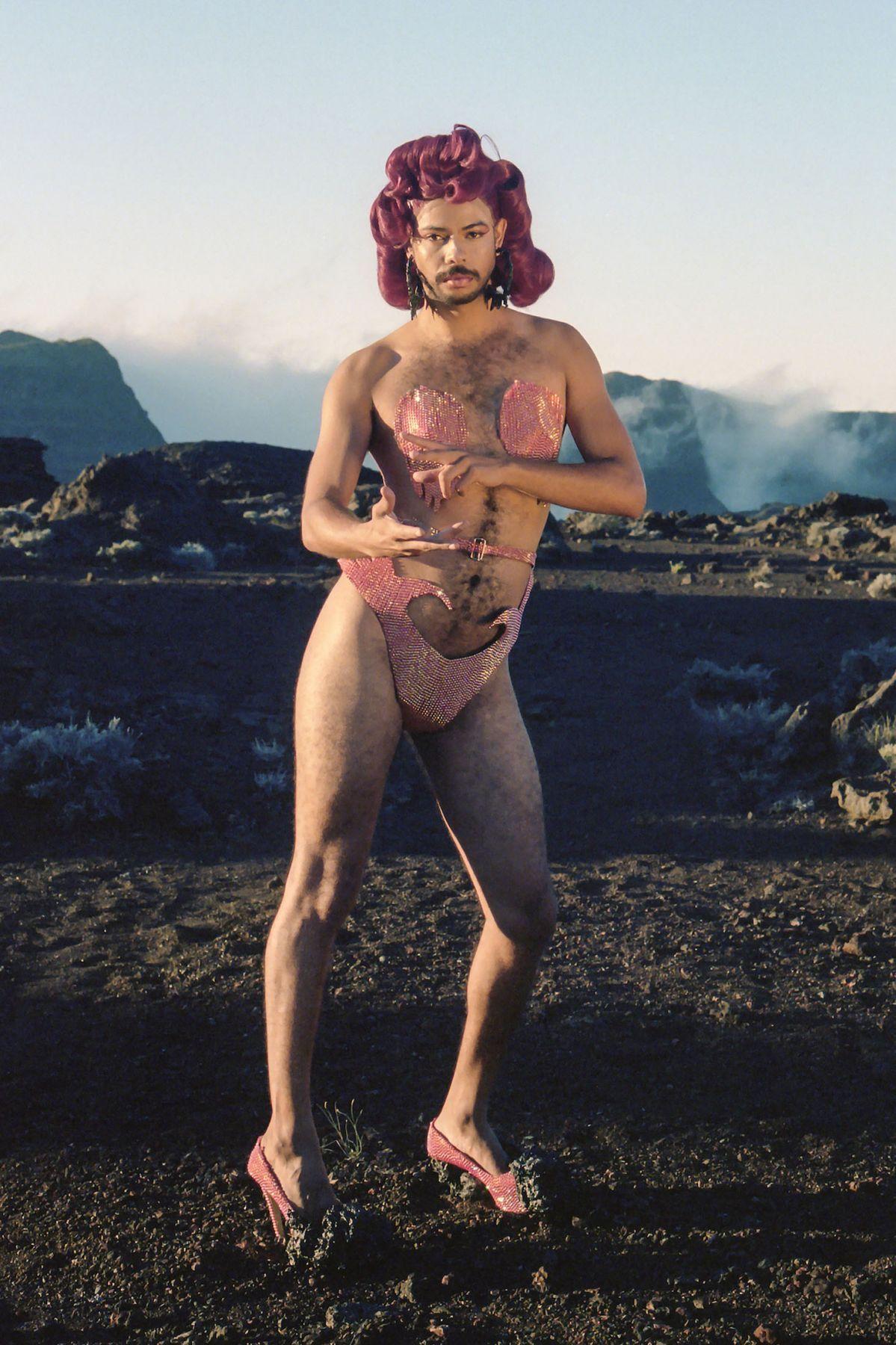

Damien Rouxel and Brandon Gercara challenge entrenched discourse and established norms. Both artists are steeped in rich cultural heritage–the world of agriculture for Damien, and the Creole culture of La Réunion for Brandon. Heritages they rejected at first before proudly embracing. Their work offers a series of new portrayals and possible collective and queer imaginaries. Brandon Gercara and Damien Rouxel are activists for LGBTQIA+ rights, each at their own level, in geographical areas where the lack (or absence) of “social space” incites exclusion. They both make use of popular culture in challenging taboos, making sources of domination that overlap and mutually reinforce one another visible, and making critical thought on Western society accessible. They participate in the careful consideration of relationships between class and gender.

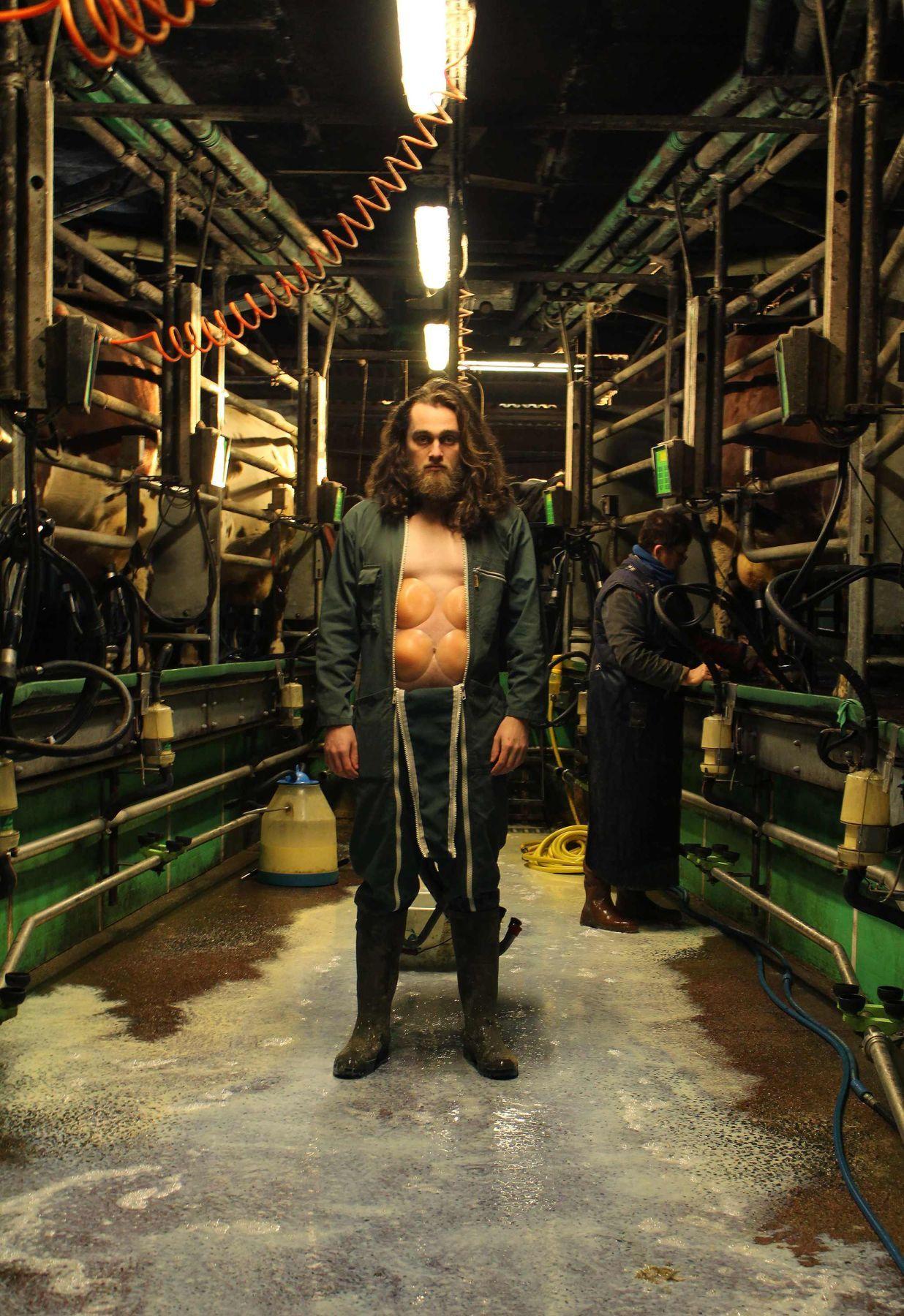

While Brandon Gercara finds his place by making community in La Réunion and other overseas territories, Damien Rouxel gets a little bit closer every day to the border that separated him from his family. On the farm, and in society, everyone plays their own role, and participates in the artist’s photography. Almost everything is natural. His sister, mother and father carry out their daily lives as they’re used to. As for Damien, he embodies the figure of the outsider, amusing himself, as always, by playing with this image, being someone different.

The environments of the artists set stages on which they create mini-performances, revisiting the conventions of Art History.

Anaïs Touchot and Marion Mounic play with conventions in contemporary art to create meeting places and allow for reconnection, responding to social, political and cultural challenges. These artists invoke the intimate and imagine spaces of resistance through processes that divert the interests of the art market, allowing for the interplay of audiences and modes of thought. They create contexts and imagine environments favorable to exchange, expression and dialogue.

Marion Mounic looks at the boundary between real and perceived experience, questions what determines identity, and challenges our perspective on the world. The artist travels between Morocco and Sète, her home base. Her work is based on her experience, observations, travels and encounters. On the street, the beach, in the kitchen or studio, she’s attentive to the gestures that reflect memory from past experience, transmit knowledge and form mini-territories in public and private space. She revisits the geographies of unifying places which combine space and time, serve as pretexts and encourage coming together, thought and solidarity.

Where Mounic focuses on action, Anaïs Touchot tackles language. She addresses us directly, offering services through posters and slogans that play on capitalist injunctions for wellness and personal accomplishment. Her work reclaims amateur activism and protests the stress placed on performance, productivity and success that burden the artist and the world. Her art is always imagined alongside its participants, protecting it from the art world, with its jargon and mechanisms claiming to determine the legitimacy and value of a piece of art.

The work of Johanna Cartier, Brandon Gercara, Marion Mounic, Damien Rouxel, Ben Saint Maxent, and Anaïs Touchot reflect the collective value of the “I”, as defined by Annie Ernaud. They go beyond the individuality of experience, emancipating and empowering us.

Aurélie Faure

Translation : Elaine Krikorian

Text produced by Réseau documents d'artistes et Aica – France, Point de vue, 2023. In partnership with The Art Newspaper France.

Notes :

1An event surrounding the murder and disappearance of a number of young women in the Yonne department of France starting in the 1970s.

CAR CRASH ACCIDENT, 2022

Car, multimedia device, football jerseys, tire, jackets, shoes, flowers, prints, beers, light

Variable dimensions

NO MORE PARTIES IN LA, 2022

Abandoned House [Villa Cameline], Nice

Installation, texts, shoes, flowers, print on blue back with acid, poppy, cut keys, video, sound, sound installation, clothes

Variable dimensions

NO MORE PARTIES IN LA, 2022

Abandoned House [Villa Cameline], Nice

Installation, texts, shoes, flowers, print on blue back with acid, poppy, cut keys, video, sound, sound installation, clothes

Variable dimensions

LA VIE ORANGE, 2022, Marseille

Installation, bottles of water, soda, alcohol, flowers, text, video, sound, colored light

Photos: Nassimo Bethomme

L'ennui rural, 2020

Video, lenght : 9'35''

Turbo, Astro, Sfumato: the infernal trio

Exhibition view Turfur at Passerelle Centre d’art contemporain, Brest, 2021.

Photo : Aurélien Mole

Vache à lait, 2022 [from the Self-portraits series]

Digital photographs, 2012-2022

© Adagp, Paris

Bloom, 2021 [from the Majik Kwir serie]

With Ugo Woatzi

Series of 7 digital prints (3 ex), 20 x 30 cm

© Adagp, Paris

Lip sync de la pensée, 2020

View taken from the video of the Lip sync performance of thought, triptych of speeches : Asma Lamrabet, Françoise Vergès, Elsa Dorlin, 14 min.

Photography and video framing © Marcel | © Éric Lafargue

FRAC Réunion collection

© Adagp, Paris

Les ombres - trio féminin, 2019 [from the serie Histoires de famille]

Digital photographs, 2016-2022

© Adagp, Paris

Trombia, 2023

Ceramic, oak wood, series of 7 spinning tops, variable dimensions (16; 22; 28 cm)

View of the Trombia Open Studio, Le Cube - Independent Art Room, Rabat Morocco, 2023.

Photo : Marion Mounic

L’guelsa, 2023

Mix media installation, variable dimensions, 2023. View of the exhibition Speed dating #6 - Les Marion(s), Lieu Commun.

Photo : Damien Aspe

Capital romance, 2023

Performance, with Clara Agnus, as part of the Grand désenvoutement chapter 23, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Invitation from Adelaide Blanc.

Photo : DR

Le Centre de Désenvoutement du Capitalisme, 2022

Installation

Exhibition view, Phakt, Centre Culturel Colombier, Rennes, 2022

Photo : DR

Grande démonstration de peinture

Performance with Clara Agnus

Invitation from La Galerie, Noisy-le-Sec, juin 2022

Photo : DR