Two Stubborn Sisters

Two Stubborn Sisters

A written fable based on three works selected by the author in the collection of Documents d'artistes Nouvelle-Aquitaine.

Once upon a time there were two false twins. They were very fond of each other but did not look at all alike. The only thing they had in common was bad circulation. A genetic predisposition inherited from their mother who, during the very first months of her pregnancy, had been obliged to permanently wear inelegant compression stockings.

“If you don’t, you’ll be sure to have thrombosis!”, the family doctor had threatened, pointing a finger at his Medical Larousse dictionary to pictures which the mother had first taken to be volcanic landscapes seen from an airplane, before realizing that they were pictures of close-up human calves.

“Oh my god”, the mother, still very young, had murmured, before swiftly slipping the prescription into her bag, and then dashing to the chemist to get her first pair of medical tights, whose brand name, Sigvaris, when pronounced by the pharmacist with much stress on the last consonant, left no doubt about her customer’s ailment.

Since then, nobody had caught a glimpse of her naked, except for a bit of her knee or ankle. Summer and winter alike, the entire lower part of her anatomy was enveloped, from the top of her thighs to the tips of her toes, in an opaque wrapper made of a mixture of merino wool, polyamide and elastane. As for colours, she had a choice of smoky black, navy blue, anthracite grey or dark brown. Over the years she became expert in the delicate task of pulling on these tights which were so vital for the health of her legs.

When the girls were small, they inquisitively watched their mother every morning carrying out a series of movements as mysterious as a pagan ritual, whose complexity was every bit a match for the digestive system of ruminants, who, as the girls had just learnt at school, had no fewer than four stomachs (the rumen, the reticulum, the omasum and the abomasum). Squeezing a leg into a compression stocking seemed to be as lengthy and difficult a task as introducing a tuft of grass into a cow’s body. Endless toing and froing, which all had to be carried out in a meticulous way, without any haste, or else the whole operation would have to be started all over again.

What had intrigued and then amused the two sisters in their childhood became a source of anxiety when they reached puberty. The gale of hormones that assailed them just after their fourteenth birthday brought them not only the usual batch of inconveniences associated with that age (acne and spots, painful periods, a sudden explosion of hairiness, recurrent glum and sullen moods, permanent apathy), but also a predictable venous insufficiency.

The girls realized that they, too, were going to have to cope with that particular anatomical disorder that had spoilt their mother’s life. There was no question, however, of wearing those awful compression stockings, even if the various brands now offered products made of extremely supple micro-fibres with daring patterns and bright colours—lime, purple, silver, sable, chocolate, mist, cinnamon. Each one of them, in their own way, decided to take the bull by the horns.

The elder sister (who clung to that title because she had been born three minutes before her twin) was tall and athletic, with a full head of blonde hair, whose curls were of an ideal diameter for harmoniously distributing the volumes of her hair on her head. A kind of hair that combined the majesty of a weeping willow with the dazzle of a field of sunflowers.

The younger sister was small, brown and chubby, with straight bowl-cut hair and sage-green eyes above a long, tapering nose. Her eyes were intense, which meant that you could easily imagine her on a horse, clad in chainmail and brandishing a standard covered with lilies blowing in the wind.

Never very keen about physical exercise throughout their girlhood (in gym classes the elder sister clung to the rings, paralyzed with fear, while the younger one refused to climb up the poles, in solidarity with her sister), the two girls became accomplished athletes once they had stopped growing. The prospect of ending up like their mother with the lower half of their bodies perpetually enveloped, even if with fine Egyptian cotton with a natural heat-regulating effect, urged them to keenly seek more efficient solutions to remedy that family weakness. One opted for swimming, the other for yoga.

As a receptionist in a large hotel in the capital, the elder sister started to work her way, five days a week, through all the swimming-pools in her neighbourhood, scrupulously noting every detail on her smartphone to enrich the database of her Swimming-pool Guide app. Her shoulders took on impressive proportions just as her problems with heavy legs faded away.

During a session in her favourite pool (50-metre Olympic size, separate showers, lockers large enough to take her trouser suits without creasing them), when she reached the end of her third kilometre using the crawl, she suddenly saw, clustered around the diving board on one of the lanes reserved for swimming schools, a group of people in strange outfits. The whole group suddenly slipped into the pool and the elder sister discovered, under the water and to her amazement, despite the growing condensation inside her goggles—an insoluble recurrent problem—, that they each had a magnificent fish’s tail with iridescent motifs, instead of legs. Seven mermaids and a triton were there in front of her, lined up and smiling like an underwater reception committee.

The elder sister took off her nose-clip, removed her ear plugs, and blew vigorously through her left nostril while pinching the right one closed, then the right nostril while pinching the left one, to clear her sinuses, before asking those people what they were doing there.

“We’re the Mermaid Academy”, explained the triton, who had a red beard and a shark’s tooth hanging round his neck.

“This is our first training session of the season”, added a mermaid with a brassiere in the shape of starfish pulled tight over her breasts.

The elder sister had never heard of that activity, but during the time it took her to dry off and pack up all her things, she learned as much about mermaiding as if she had spent all afternoon looking at tutorials on the subject.

The triton was called Ludo, he was the group’s coach, and he much enjoyed talking a lot between two sequences of figures, free-diving.

“In addition to harmoniously muscling the whole body, it’s a playful and liberating practice”, he explained, adjusting his fish tail with blue and white vertical stripes which made him look a bit like Obelix, but in a fit and smooth-skinned version. His red hair and naked torso probably counted for more than a little in that comparison.

“For a long time I’ve had trouble with my body”, Ludo the triton went on, “and mermaiding has helped me to become someone else, it’s helped me to deal with the way other people look at me, and accept myself as I am. Under the water, nobody bothers me anymore, I can finally be myself.”

Ludo was in charge of the fish in the pet section of a garden centre. With a passion for water since he was small, he had done a lot of swimming before giving it up.

“Not enough daydreaming”, he said, fiddling with his shark’s tooth, before ending the conversation with a backward pike dive that emphasized the curve of his hips.

That same evening, the elder sister got back home with stars in her eyes and a registration form in her pocket. A mermaid was born. She soon put away her flippers, pull-boys, paddles and kickboards, and replaced them with a splendid royal blue neoprene tail, complete with a patented one-flipper system that was unbeatable value for money.

From every point of view, that activity had nothing to do with traditional swimming. It helped you to develop muscles that you were not even aware you had. But above all it opened the doors to an imagination with an unsuspected potential. The elder sister became totally committed to this new passion, to such a degree that after a while the walls of her living room groaned under the weight of all the medals won at competitions, which were first local, then regional, then very soon national, and finally nothing less than international. Mermaiding was in the process of totally changing her life. She decided to make it her profession and to go back to her studies. She became a part-time professional mermaid in the country’s biggest aquarium, while at the same time preparing a PhD dissertation on the Myths, symbols and archetypes of the submarine world in Disney productions, supervised by an eminent professor of semiology specializing in cultural studies.

A few hundred miles away, the younger sister, for her part, would watch the ocean rise and fall without ever dipping a toe into it. She preferred air to water. She lived at the western tip of the country, in a flat, wind-lashed countryside where, here and there, rows of huge stones rose up in the middle of the meadows. People came from afar to admire these mysterious arrangements, which dated back nobody quite knew exactly how many years, and gave rise to all manner of hypotheses, some more far-fetched than others.

After a paramedical training that was not to her liking, she had switched to renewable energy. A night school programme, followed selflessly for more than three years, had enabled her to obtain her degree in electrical engineering, and then land a job as inspector in a large on-shore wind farm in the region.

She liked climbing to the top of those modern heirs to windmills to look out over the landscape as far as the eye could see. In front of those rows of perfectly aligned masts, she had the impression of being at the head of an army of knights in white armour, just waiting for a sign from her to swirl their swords.

Between two wind turbine inspection jobs, the younger sister assiduously practiced yoga. It was her throat doctor who had first talked to her about yoga, when she was complaining for the umpteenth time about hot flushes in her legs.

“First off, try the tranquil lake position, you’ll see that it’s very easy and it gives instant relief!”, the doctor had said as he stamped a prescription covered with spidery handwriting that would cause the local pharmacist to sweat.

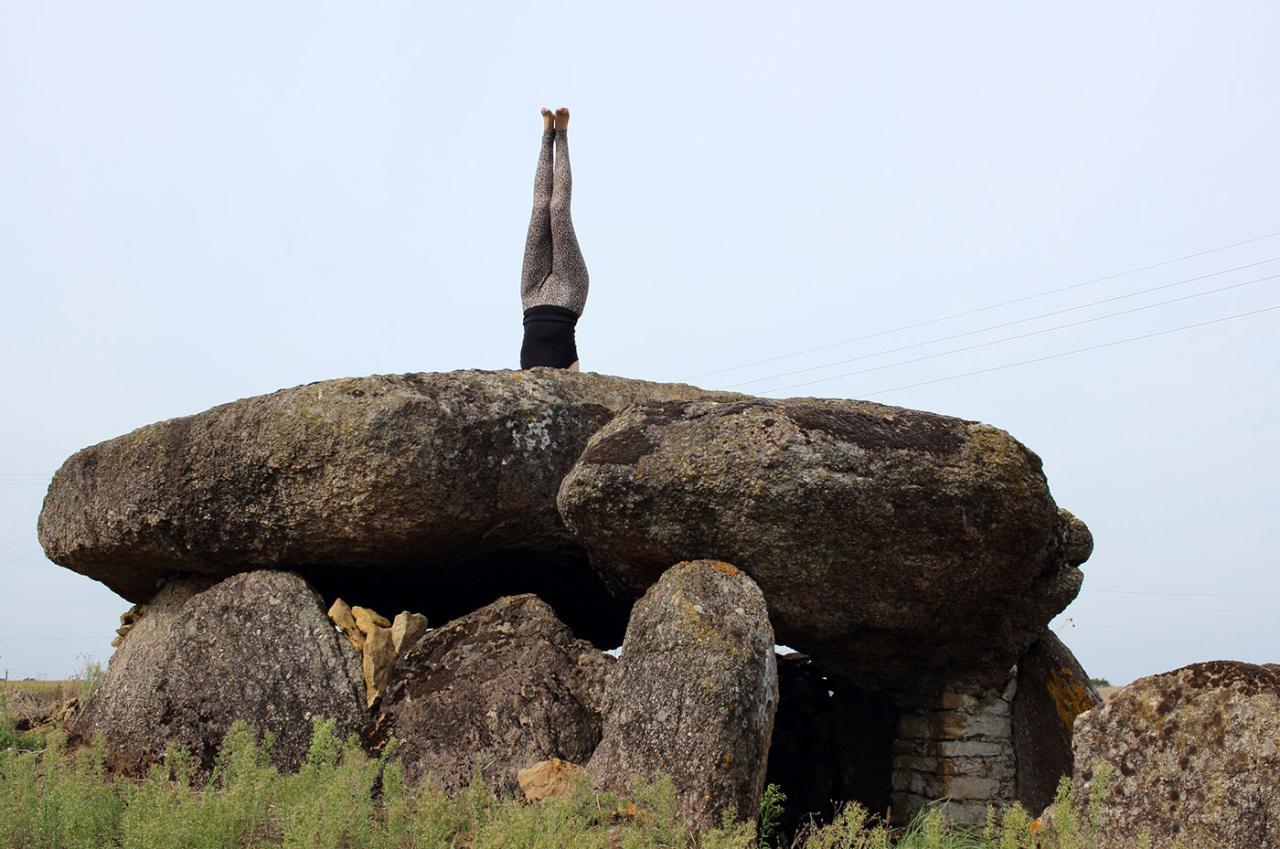

The younger sister had not stopped at the tranquil lake exercise; she had quickly become acquainted with all the positions taught in the Shambala yoga centre which had just opened beside the small supermarket. Reverse table, standing forward fold, downward facing dog, locust, cow, happy baby, bound lotus, seated twist, cobra… she did all the poses with a mastery which even amazed her teacher, a young woman from the East, supple as a piece of seaweed, whose pitch of voice was already a therapy in itself. She was the first in her group to successfully achieve the royal position, the one which involves standing on your head with your elbows and legs stretched skyward, which some people more prosaically call the pear tree. That figure was a blessing for all her organs, so she started to practice it everywhere, and at any time, whenever she had a chance. One summer, local people were thus able to see her, early in the morning, before going off to work, in the royal position on a dolmen beside the local road leading to the wind farm.

The two sisters calmly reached the age of thirty, embarked on their forties full of confidence, and approached their fifties with determination. The elder sister had married Ludo the Triton, while the younger one had set up home with the young seaweed-like teacher from the East.

When their mother died of a brain haemorrhage at an advanced age, they buried her in a small cemetery on the edge of a forest, halfway between the capital, where the elder sister trained, and the regional wind farm which the younger one managed. In the simple pale wood coffin that they had chosen, they surrounded their mother with all her compression hose. There were a good hundred pairs of tights, of all colours and materials, rolled up in compact balls, still emanating the sweet smell of the lavender bouquets with which their mother decorated all the furniture in her bedroom. Looking at her body lost in the mist of that mass of multi-coloured balls, the two sisters remembered the pool full of balls in which they played as children when their mother left them at the day-care centre in a Scandinavian furniture shop, while she went and bought a new pouffe for her feet, or a new duvet cover on sale with its two matching pillow-cases. They smiled without needing to explain themselves, then they closed the coffin for the last time.

After the ceremony, once they had thanked the priest, and accompanied the few relatives present to the cloakroom of the restaurant where they all had a meal, they decided to go for a walk in the forest. They had drunk a little too much, so they soon got lost.

Reaching a clearing, they came upon a small lake, or rather a pond. The younger sister suggested they have a rest, so they lay down in the grass head to toe, with the face of one sister opposite the calves of the other. They went back over all the sad moments and funny episodes of their childhood, told each other about the worries of their present-day lives, and regretted that they had not seen enough of their mother recently. Above them an aspen swayed its foliage, which made a continual and comforting noise.

“It would be good if she could beckon to us from where she is, a falcon’s flight or a jay’s cry”, said the younger sister looking up at the tree-tops.

“Or a frog’s dive”, said the older sister who had a view over the pond.

But nothing happened and the glasses of rosé wine drunk too fast with too many salted biscuits soon had their effect. The sisters slept like two entwined logs amid the grass.

The following morning they were awoken by the din of a military aircraft flying very low. The patch of sky above the clearing was suddenly divided into two by a long white zip fastener. The elder sister reacted with a series of yawns, the younger with a string of swear-words. They did not have the same temperament.

They made the most of the pond to have a wash, before brushing off their clothes with the palms of their hands. The elder sister’s wrap dress with dolphin motifs was all crumpled, and the younger one’s wild silk dungarees were full of fir needles.

It was at that moment that they saw the thing, at least ten yards from where they had slept, near a clump of ferns. They slowly approached it and then stop, dumbfounded.

It was the size of a child’s swimming pool, about 20 inches deep, with its sides cut clean like a slice of cake. From a distance, you would have said it was an arrow-shaped crater, but close to there was no doubt what it was: a dinosaur’s footprint. More exactly, the footprint of a theropod, because it had three fingers. The sisters had a few rudiments of palaeontology, ever since their mother had taken them to the east of the country to visit the educational trail called In the footsteps of giants, when they were eight or nine. That outing had left them with a vivid memory, and not just because of the life-size concrete creatures lurking behind bushes, which scared children.

They crouched down and warily touched the still damp sides of the hollow: the earth had not had time to dry, it was clearly from last night.

The two sisters remained there for quite a while neither moving nor talking, they did not know what to think, or more exactly each one of them had their own little idea but did not dare to put it into words. They looked at each other, nodding their heads, a common way of dealing with their awkwardness and confusion, before retracing their steps to fetch their bag, and then follow a path that would definitely take them somewhere, to a farm, a bus stop, a camp-site, a freeway rest area, a housing estate, a chapel, a gas station, a football pitch or an industrial zone, from where they would perforce find a way of getting back home.

Moral: The mother’s death does not do away with the Earth’s attraction.

Translation : : Simon Pleasance & Fronza Woods

A written fable based on three works selected by the author in the collection of Documents d'artistes Nouvelle-Aquitaine :

Suzanne Husky, Sur la prolifération des sirènes au temps de naufrage, 2017, video, 25 min. 35 sec. (a production by the Centre international d’art et du paysage de Vassivière, as part of the exhibition Des mondes aquatiques #1, 2017).

Julie Chaffort, J’ai une passion… 2015-2017, photographic reportage (series of 332 photographs, a commission by the Communauté des communes du Pays de la Châtaigneraie in the Vendée department).

Laurent Le Deunff, Jurassique France, 2016, dinosaur footprint and ‘fossil’ plants, at the Arceau pond, Parc du Pilory de Campbon (Pays de la Loire) [a production of @Tripode et Mosquito Coast factory].

video, 25 min. 35 sec.

[a production by the Centre international d’art et du paysage de Vassivière,

as part of the exhibition Des mondes aquatiques #1, 2017]

photographic reportage [series of 332 photographs, a commission by the Communauté des

communes du Pays de la Châtaigneraie in the Vendée department]

dinosaur footprint and ‘fossil’ plants,

at the Arceau pond, Parc du Pilory de Campbon (Pays de la Loire)

[a production of @Tripode et Mosquito Coast factory]