Counter-performances

Counter-performances. John Deneuve, Myriam Omar Awadi and Nicolas Puyjalon

In Perform or Else, John McKenzie traces back the rise of the term “performance” in the post-war years by identifying the three paradigms that make it a key to understanding the times. At once a mode of artistic experimentation, a neoliberal model of organisation and one of the forms taken by the industrial project, performance can be boiled down to the expression the same type of efficiency, understood, definition-wise, as an “accomplishment”. However, not all artistic performances fit into this pressure to succeed that underlies late-stage capitalism. As a matter of fact, many of them seek to promote failure and lack of mastery, and to establish themselves as critical apparatuses of productivist ideology. This is the case of John Deneuve, Myriam Omar Awadi and Nicolas Puyjalon’s counter-performances. For each of these artists, the refusal to subscribe to the pressure to succeed is a constitutive element of aesthetic styles – badly crafted, deceptive or inconsequential –, which, despite being deprecated, often turn out to be emancipating. By making use of these resistances that are in fact not resistances or do not seem to be, they encourage art to free itself from any functionalist premise.

The loser: An oppositional identity

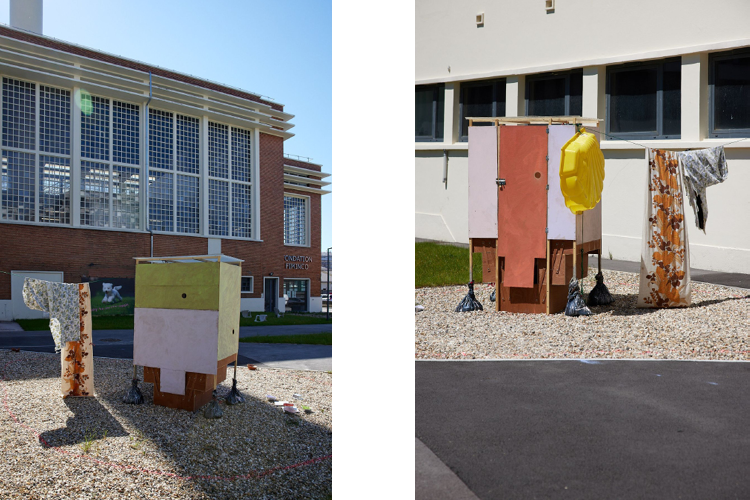

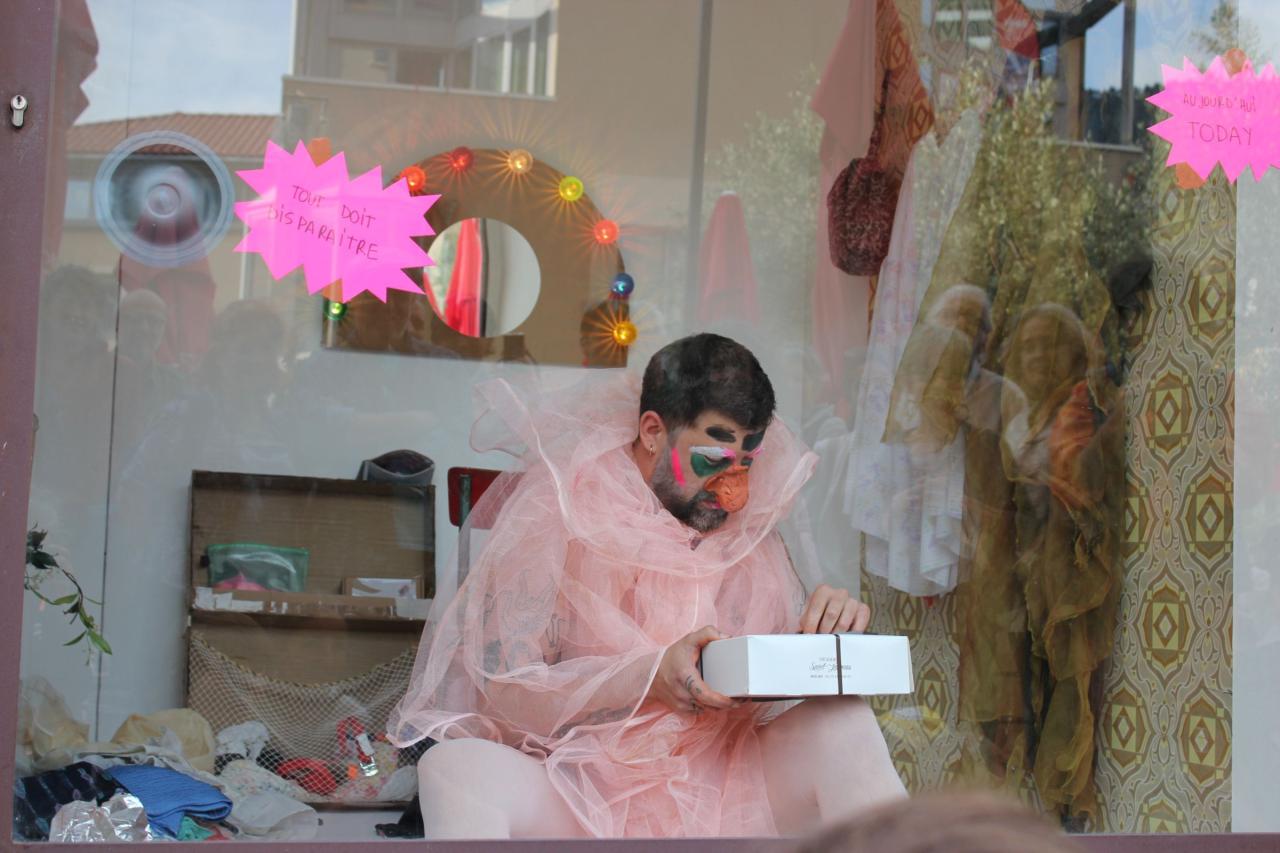

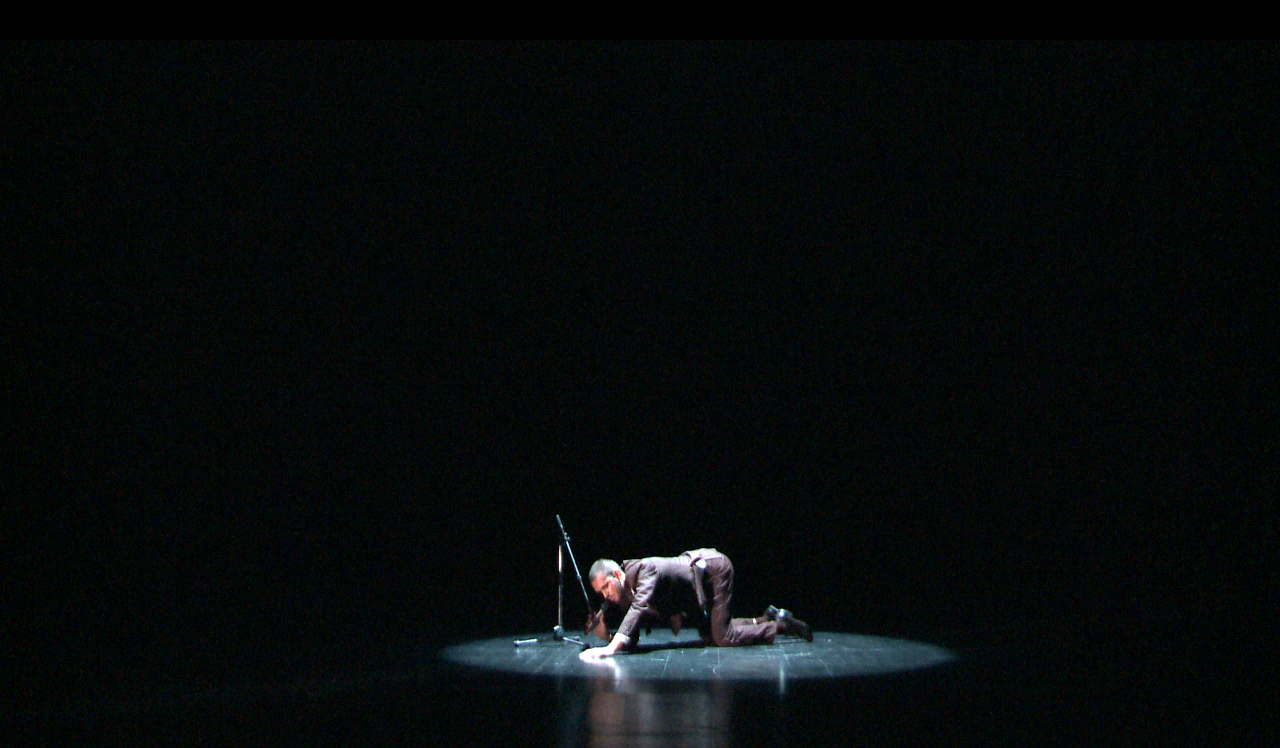

Using an alias that signals her resistance to identification, John Deneuve acts as an anti-heroine in spandex or glittery outfits who uses a stepladder as a makeshift gym apparatus that she never really climbs onto or, whenever she does, does so without an ounce of grace or agility. Thus stripped of any aesthetic pretension, her performances give her art – which does not claim to be elevated in any way – the appearance of a gym exercise devoid of any orthopaedic nor spectacular goal. As expressions of “disability aesthetics” – a forgotten marker within modernity, according to Tobin Siebers1 –, they deconstruct idealised depictions of the competitive body and of the virtuosic artist, bolstered by her candid and intentional energy. Fearless of ridicule, the gesticulating Wonder-John Deneuve2 and her dislodged attitude and vertebrae gets revenge for all the bumbling ones they call “good-for-nothings”. A queeresque hybrid of a tattooed clown and a mischievous bear, Nicolas Puyjalon also sides with the outsiders, the debauched, minority bodies and tired subjects. Much like his crude makeup and shapeless outfits (a deconstructed amalgam of pieces of string, rags and tulle), he displays a lack of decorum that mirrors the precarious constructions that he cobbles together. Whether he is trapped in piles of chairs (La revanche des chaises [Revenge of the Chairs], Commettre l’irréversible [Committing the Irreversible]), trying to catch the stars (Au clair de la lune [By the Light of the Moon]), striving to find refuge in a makeshift shack (Homo Faber) or risking the collapse of a precarious structure (Le Mont analogue [Mount Analog]), he constantly exposes himself to failure with a casualness matched only by his melancholy. Over the course of his various works, the character that Puyjalon embodies paints the portrait of an ageing body that no longer fits within the ideals of the times, a life form that wears itself out by risking everything (Vieillir [Ageing], Les Sommes [The Naps], Débauche de fatigue [Orgy of Weariness], L’Après-midi d’un bears [Afternoon of a Bear], Soupirer en confiance [Sighing with Trust], Garçon Glouton [Greedy Boy]…). This identification with the loser also comes into play in Myriam Omar Awadi’s work, in which she appears dressed in a shimmery dress, poking fun at the “brilliant” nature of the artist by recounting a creative process mired in failure (The Artist Is Shining) – a motif that also appears in the stammering of a crooner singing a litany of jilted loves on all fours, or in the figure of a defeated boxer (OHOUI – Étude pour une chanson d’amour compressée [OHYES – Study for a Compressed Love Song], Russel Avril, 5 défaites, 1 nul, 4 ko [Russel Avril, 5 Defeats, 1 Draw, 4 KOs]). The figure of the loser takes on a more political turn when it becomes a channel for those who have lost their voice as well as their sovereignty, as is the case with the songs of the Comorian women who were deprived of their matriarchal authority in colonial times. By substituting the hegemony of Western discourse for the complexity of oralities in the Oceanic-African-Asian region, Myriam Omar Awadi “rekindles the fires”3 of powerful voices that shook foundations all the way to the medina, and in doing so invites us to consider the force of their insurrection.

Going limp, or the enjoyment of impotence

This off-centring approach is particularly striking when the performance favours desire over truth, and therefore assumes the stance of postmodern criticism to position itself beyond the binaries (man/woman or learned culture/pop culture) upon which domination dynamics are based. It is a case of deconstructing the modern figure of the sovereign subject and the phallocentric subconscious that it promotes in order to implement a different kind of performativity of power.

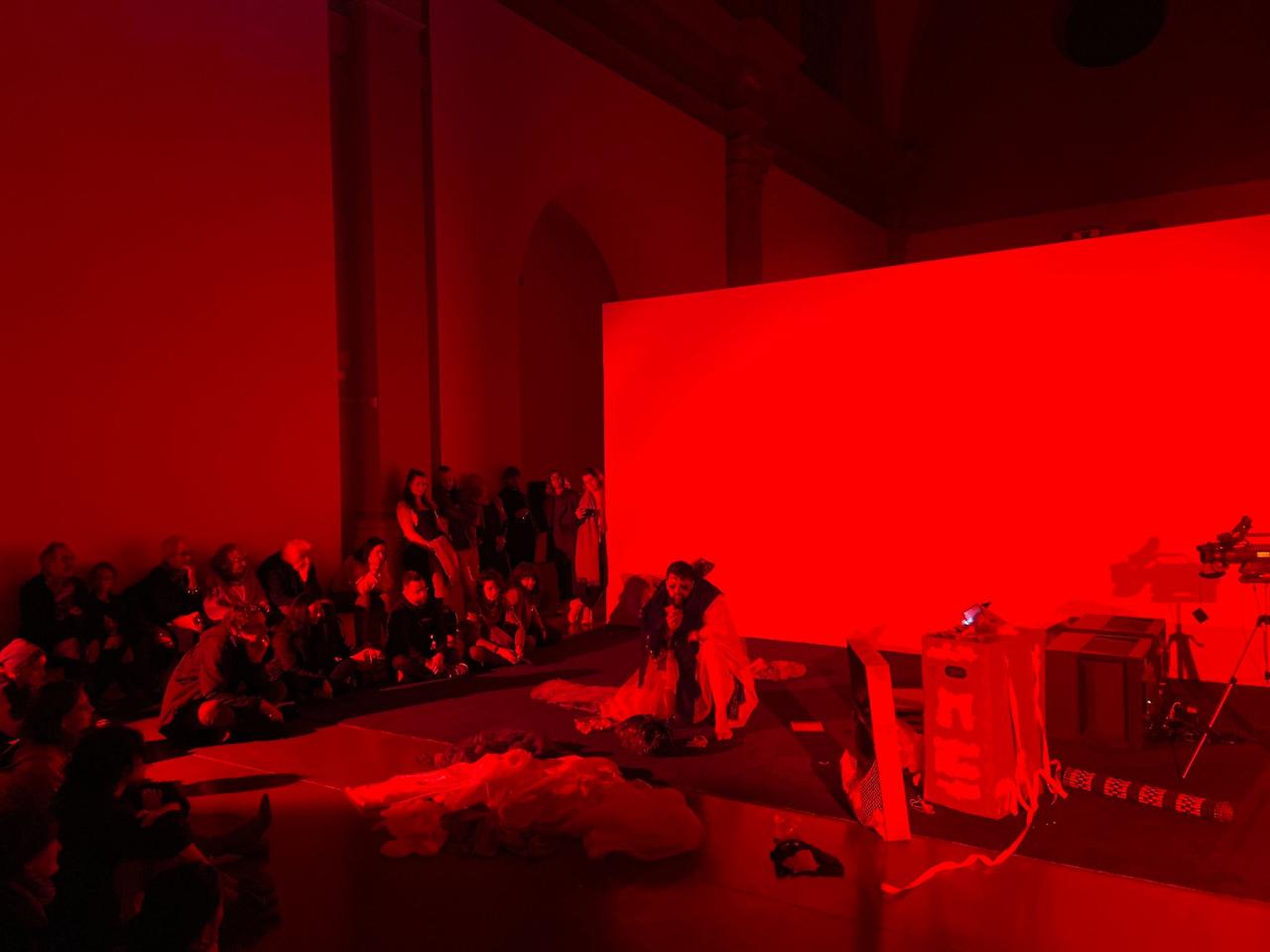

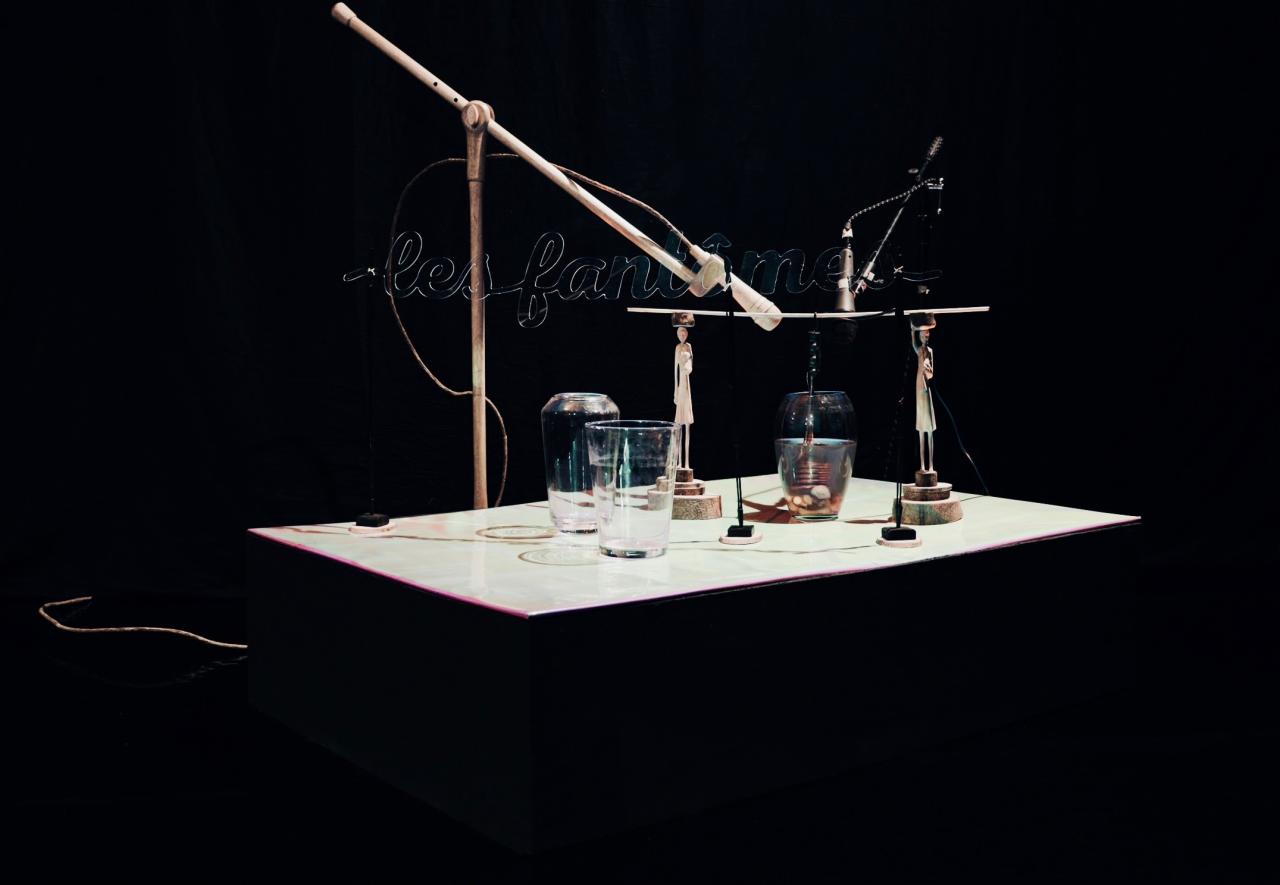

In The Queer Art of Failure, Jack Halberstam suggests that asserting a deviant identity is a subversive way of failing to be dominant. In Nicolas Puyjalon’s work, this hijacking of the heteropatriarchy manifests in playful ways, as demonstrated by the half-deflated tower that he and Zabo Chabiland crafted out of inflatable mattresses, and which acts as an antiform that opposes the turgidity of corporate buildings. The duo proceeds to deflate the tower by applying all of their weight onto it, letting the air blow out into tinkered wind instruments, which then let out the pathetic music of flaccidity. Equated with the music of post-coital dysphoria, the sounds produced ring out like a counter-revolutionary chant, conveying to whomever wants to hear them the destitution of phallic power (Nothing Else Mattress). Between bitch (beta) and she-wolf (alpha), John Deneuve revels in playing the fool and the madwoman in order to let loose an uninhibited libidinal life free of any power play. Moving to the beats of zingy minimalistic electropop,4 she opens up a space for release, in which her primal, trashy and regressive gestures (playing with a turd-shaped tube, whacking a bone with an inflatable dog) are at odds with conventions. Buoyed by straightforward eroticism and a crude and cutting form of humour, she manipulates totem sculptures and fetish objects and lets her lesbopoetic flair rip. Overseriousness is too heavy a weight for those who would uninhibit her desire. Myriam Omar Awadi, on the other hand, relies on gentleness to deconstruct the attributes of dominant masculinism. The amplified vibrations of a sex toy that the artist seeks to pacify to the sound of a Madagascan lullaby takes on the guise of a quivering, flaccid penis, the vulnerability of which acts as a symbolic reparation. The title of the performance, Les pénis pleurent aussi [Penises Also Cry], which refers to Resnais, Marker and Cloquet’s acclaimed film, emphasises the idea of an organ void of substance, emptied of its potency, as if it were fetishized by the patriarchy. Myriam Omar Awadi also pays tribute to feminine subversion by alluding to Debe, a clandestine dance during which women recount their intimate lives, in a combined act of irreverence and resistance. In her work, she uses the recurring motif of the orgasm5 as a cry of emancipation for all women, which, through a dissymmetrical effect, seems cut short and lacklustre when associated with men – stuck in the throat of a flaccid crooner who can barely stand up straight.

Radically free

This deflation of manly glory has led all three artists to embrace the repertoire of laxity, fun and idleness to refine their criticism of triumphant capitalism. Thus brought back to its “inoperative” sense – an opus that dissolves as soon as it is made, to quote Frédéric Pouillaude’s terminology6 – the performance acts out the fundamental unproductiveness, incontinence and futility of an art that evades any capitalist calculation.

To the vision of the island of La Réunion as a “piece of confetti” in the French colonial empire, Myriam Omar Awadi opposes the trifles of vernacular gatherings, which she portrays as celebrations running idle: deserted karaokes, vacant concerts or theatres of almost no consequence (particularly in the projects Variétés [Varieties] or Orchestre vide. Karaoké de la pensée [Empty Orchestra. Karaoke of Thought], created with Yohann Quëland de Saint-Pern on the occasion of the “Paroles, paroles” laboratory). In Chiromani boule à facettes [Chiromani Disco Ball], she presents us with a dancer clothed in traditional fabric, dancing in circles, with light from the projectors bouncing off her sequinned outfit, in a choreography of frustrated expectation that urges us to enjoy her sole presence. The staging of this utterly unproductive exertion further emphasises the sense of idle poetry that suffuses her performances – “IN(ACTS)”7 that tie the act of doing nothing with inopportuneness, with the suspension of the present moment outside of functional cycles. The DIY nature of popular celebrations is also present in a more insistent form in John Deneuve’s performances, which combine cheap props (bunting, balloons, streamers, masks and pointy hats) and unruliness. She demonstrates this by performing disorder in a school, where bodies are usually made to behave, prompting an initially obedient classroom to sing and laugh atop their desks,8 or turning the controlled lockdown environment into a window opening up onto a delightfully absurd domestic carnival, a literally priceless joyful chaos.9 Through his use of the grotesque, Nicolas Puyjalon also crafts new ways of being-in-the-world based on derision and the rejection of decorum. His burlesque shenanigans take on the boisterousness of an inattentive child prancing through a museum on a cardboard horse (À Dada sur mon bidet [This is the Way the Ladies Ride]) or almost vomiting as he eats off the floor of a café (Il faut tout un village [It Takes a Village]. Caught amid this dramaturgy of mishap, he carries out one failed attempt and useless effort after another to perform a clownish tribute to vanity, humble lives and fragile bodies. When chaos and nothingness reign supreme, any failure can become a weapon for the weak.

John Deneuve, Myriam Omar Awadi and Nicolas Puyjalon’s counter-performances are akin to the notion of “nonperformance”, as theorised by Fred Moten10: they all carry out a strategy aimed at sabotaging the capitalist machine, which involves the art of slowing down, of crafting poorly, of embracing dysfunctionality. In times when art has never been more threatened by capitalism’s extractivist agenda, they use efficiency and non-action to reassert its potential for antagonism, turning their shortcomings into dissidences to better celebrate those who succeed in not being what is expected of them.

Notes:

1 Tobin Siebers, Disability Aesthetics, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 2010.

2 This name isn’t the artist’s chosen name, but rather refers to the character in her videos Wonder Wall and Wonder Ladder (2015).

3 From the title of her exhibition-project “Les feux que vos derniers souffles ravivent” [The fires that your last breaths rekindle] (2022), presented at Fondation H (Madagascar) and Zeitz Mocaa (South Africa).

4 Which she uses in the context of her projects Bain de minuit (with Olivier Le Falher), Sugarcraft (with Doudouboy), Audace (with Doudouboy and Bernard Grancher) and Cancan (with Fred Berthet).

5 Particularly in the drawings Nature morte et petite mort [Still Life and Little Death] or in the performance OHOUI – Etude pour une chanson d’amour compressée [OHYES – Study for a Compressed Love Song].

6 Frédéric Pouillaude, Le désœuvrement chorégraphique, Paris, Vrin, 2009.

7 From the title of a series of pieces about inaction, reverie and expectation.

8 During a live performance for Sonic Protest 2012, in collaboration with Sugarcraft.

9 Performances de confinement [Lockdown Performances] (2020).

10 Theory developed on the occasion of his “Blackness and nonperformance” lecture at MoMA in 2015.

Translation : Lucy Pons

LISTEN HERE