Emmanuelle Nègre

Experimental fictions

Despite the diversity of its formats, materials and time-frames—films, installations, performances, cine-concerts…--, Emmanuelle Nègre’s work has an underlying logic which is forever sounding the status of moving images, whether these latter belong to the grand history of the arts or whether they hail from the eclectic world of the anonymous. If the artist thus takes from the film pantheon, for example, Alfred Hitchcock in her work Remake (2013) or Stanley Kubrick with Slit Cam (2016), she also appropriates vernacular archives whose origins we usually know nothing about, such as Unwind (2010), a juxtaposition of panoramic shots taken by a nameless cameraman in Norway, or Unknown Portrait (2008), the revealing title of a Super-8 film, digitally remade, which questions the way the image scrolls past as well as our ability to make up the story of a woman whose face we can see, but about whom we know nothing.

This is a particular point which it behoves us to emphasize, because there is a great temptation to place Emmanuelle Nègre’s works just in that category of film that we call “experimental”. In fact, even among her works which seem to have to do with this film genre, such as Collage (2009), where the material nature of an indeterminate 16mm reel is explored on its margins as well as in its interstices, we note that the fiction, even if only embryonically, singles things out: a fragment of a nose, a chin, part of a forehead all emerge, and through this emergence arouse the viewer’s imagination, opening onto a fictional time-frame which goes beyond just the film’s length. The fact that cinema’s narrative dimension is questioned as such is what is differently demonstrated by Pre-sold-titles (2014). These “impressions”, which can be observed in light boxes, are presented like a “superposition of titles coming from trailers of [different] films with one and the same hero” (Tarzan, Frankenstein, Dracula…), as the artist points out, which, for her, is a way of probing these “sure values” of mainstream production, those films of heroes and super-heroes who bestir a “very special craze for certain narratives/fictions”. The sedimentation of the titles in Pre-sold-titles thus gets the viewer to involve his degree of expectation in the cinema, at the level of the story which he intends to follow on the screen, or of the pleasure he ordinarily experiences.

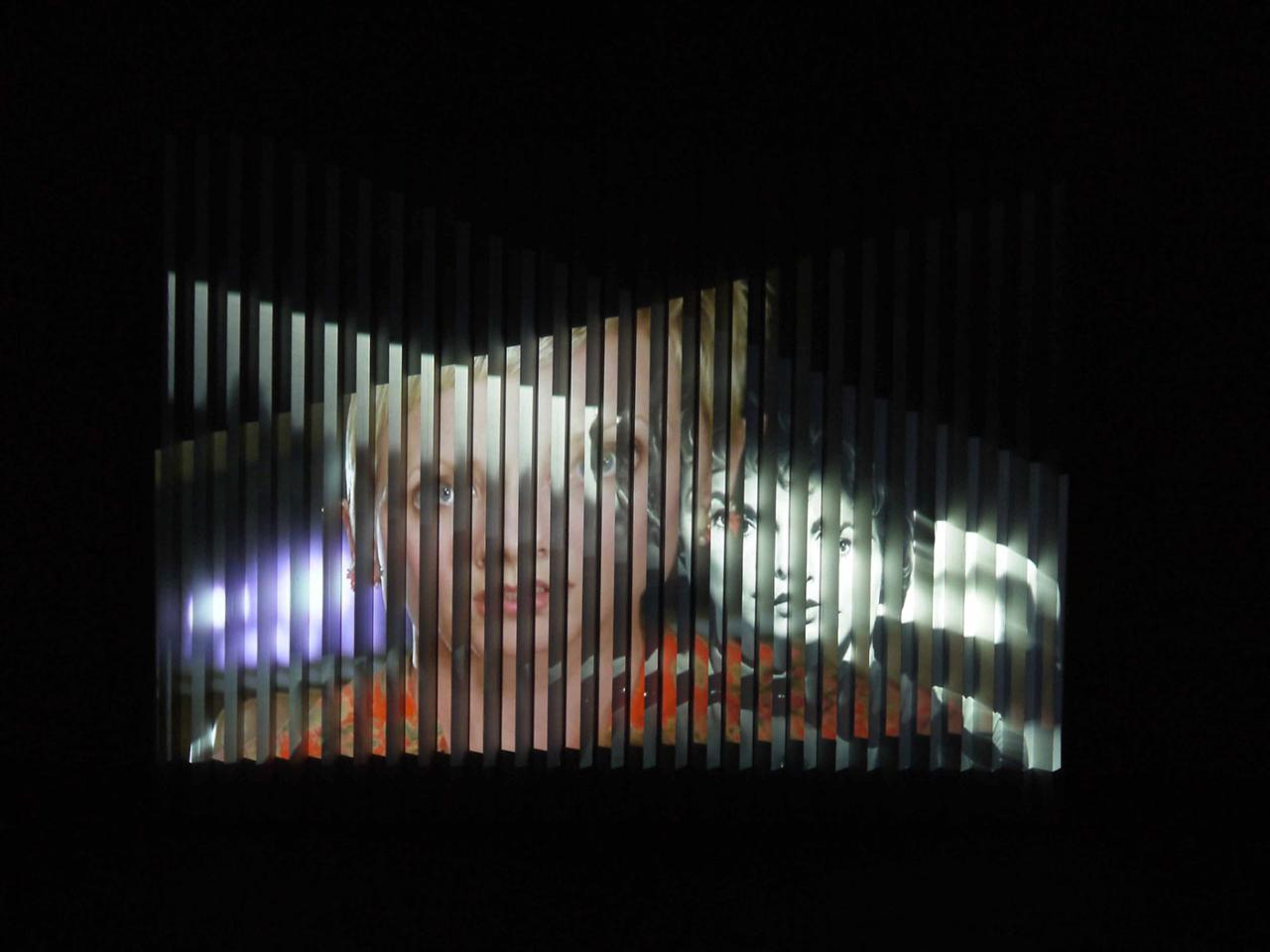

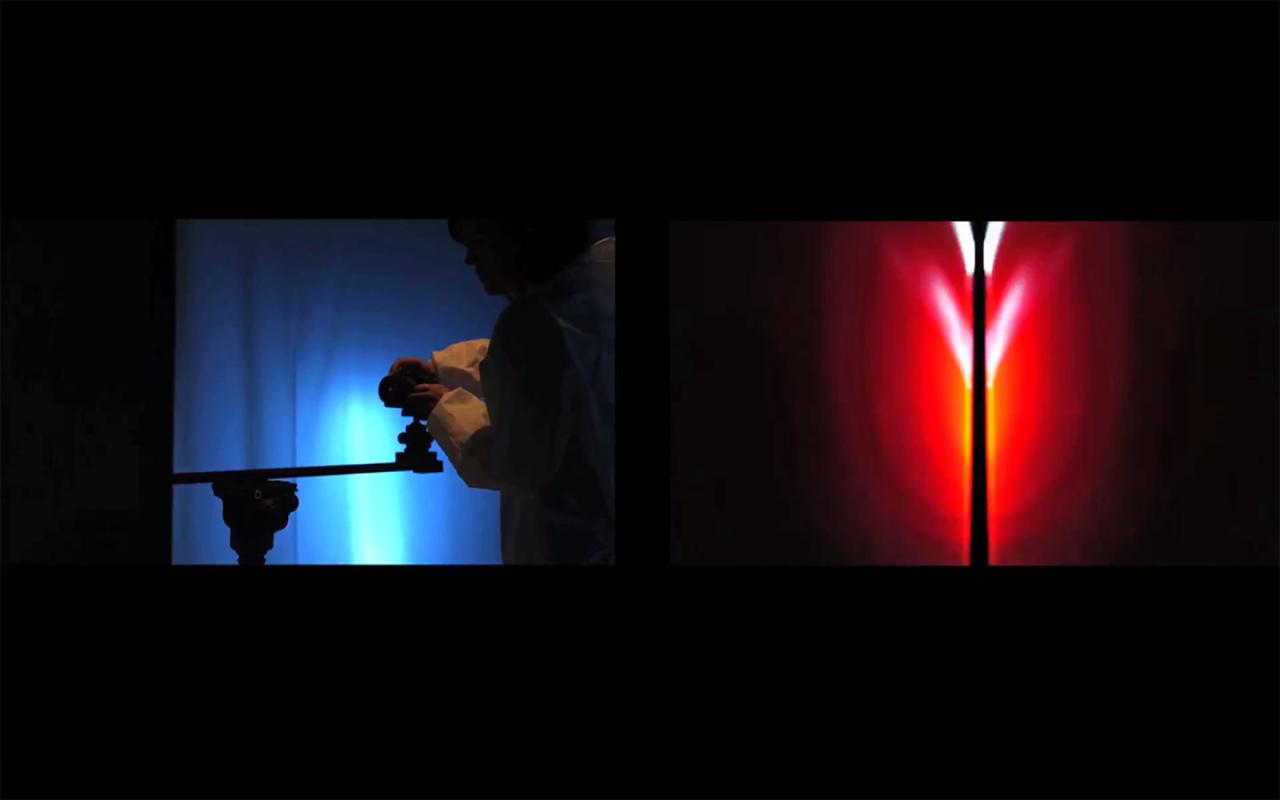

If Emmanuelle Nègre deconstructs the relation we have with dominant fictions, this is not in order to re-introduce the ruinous clash between an art of images, which cinematic masterpieces are part and parcel of, and a set of entertaining images aimed at a supposedly non-erudite audience. There is no hierarchy of values, but just a desire to examine the hold that the animated image creates in our daily lives: how films emotionally penetrate us and how they go hand-in-hand with our existences, over and above the screening time in the auditorium. In this sense, Remake is a meaningful installation which, on a multi-directional screen, mixes Hitchcock’s original Psycho (1960) and its remake, shot by shot, undertaken 28 years later by Gus Van Sant. Remake is not an extra analysis of the place of Hitchcock’s film in the contemporary art world. If Emmanuelle Nègre’s work is earmarked for museums, it nevertheless makes full use of the cinematographic experience of Hitchcock’s work, one of the most suggestive in the history of film, one which traces, as Jean-Luc Godard had glimpsed, a “control of the world”, which is to say an unprecedented capture of the viewer’s emotions. It is this selfsame, almost hypnotic effect that Gus Van Sant wanted, in his turn, to stage in his remake. Emmanuelle Nègre creates from the combination of the two films a third scene of investigation, which she describes by bringing in a strictly filmic terminology: the two Psychos work respectively, and alternately, as the “field” and the “counter-field” of the viewer’s vision, whose movements in space thereby encourage a mental montage. This spectator-cum-visitor then comes up against the very particular issue of knowing what is the remake of one film in another, just like the type of narrative that results from it for him.

What is more, this issue of the remake, or more precisely of re-editing, runs through many areas of Emmanuelle Nègre’s work. With, very often, the outline of a fiction resulting from the juxtaposition of images, without this juxtaposition being intended to relate one story in particular, especially when these images come from a set of films whose source is not given. A fine example, in this sense, seems to us to be 1448 (2016), a work made up of 1,448 photograms which the artist extracted from out-takes from silent 35 mm films found in a box sold on the Internet. Despite its seeming disorder which creates a very fast sequence, the editing nevertheless shows a rational order where it is the similarities between the narratives that become gradually more salient. This is illustrated by the thematic groupings of images of cars, building façades, people on the phone, couples kissing, various animals, airplanes, and so on. As if Emmanuelle Nègre had tried to isolate, with Paul Blackburn’s haunting music in the background, the atoms of fiction which go to make film in a thousand and one ways. This is probably one of the obsessions in her oeuvre, running through her works in their very great variety: the fact that the images come from an apparently experimental cinema (Pellicule, 2009), whether they hail from family archives (Seaside, 2018) or whether they re-enact a film that is virtually impossible to relate (2001, A Space Odyssey, made by Kubrick, and re-used in Slit Cam, 2016), what is involved each and every time is accompanying their narrative potential, whatever it might be, and doing so in a world where we thought we were saturated with history, but where we discover with Emmanuelle Nègre that there is in reality never enough.

Dork Zabunyan.

Translated by Simon Pleasance & Fronza Woods

Impressions, boîte lumineuse

Impressions, boîte lumineuse

Impressions, boîte lumineuse

Ecran multidirectionel, video projecteurs, films: « Psycho » 1960 and « Psycho » 1998

03:20 , 35mm photograms, found footage Musique: Paul Blackburn

03:20 , 35mm photograms, found footage Musique: Paul Blackburn

03:20 , 35mm photograms, found footage Musique: Paul Blackburn

2:07min, 16mm

01:35, 16mm, digital

03:43, 16mm, digital, Musique : Geoffroy Boulier

Double écran, Vidéos