Émilie Perotto

Sculpture as a project

While Émilie Perotto is an artist, in the sense that she sculpts and writes, produces commissioned works, and is exhibited and featured in public and private collections, she doesn’t consider herself to be the “creator” or the “author” of her sculptures. In fact, she doesn’t refer to them as “works” but, rather, as “projects”. She shapes and reshapes forms, materials, their status and their uses.

All this is achieved without any mystical purpose, with no mysterious intention or particularly anti-conformist stance. Émilie Perotto simply deems herself “an intermediary, a translator, a facilitator” or a “purveyor”1 of her own works, of which she does not claim to be the direct creator. To her, a position of humility is inevitable, in the sense that she cannot affix her sole name to a body of work that relies on mutual aid and discussions. The act of giving a prototype to someone so that they process it according to their own skillset or mastery of a specific material is a necessary step in her work method. The moment in which the sculpture passes into someone else’s hands helps the artist understand the industrial world that surrounds her. For all intents and purposes, her sculptures are attached to her name and her parentage to them is undeniable. However, while the art world might insist that these productions are indeed Émilie Perotto’s — a distinction that certainly wouldn’t be as clear-cut in the world of design —, the artist still considers her involvement to be limited to this “simple” parentage2. What ends up shaping the sculptures is their coming into contact with the people they are entrusted to, and who then manufacture them. Although this has occurred less in recent years, it explains why some of her pieces are co-signed3 or presented under a pseudonym4.

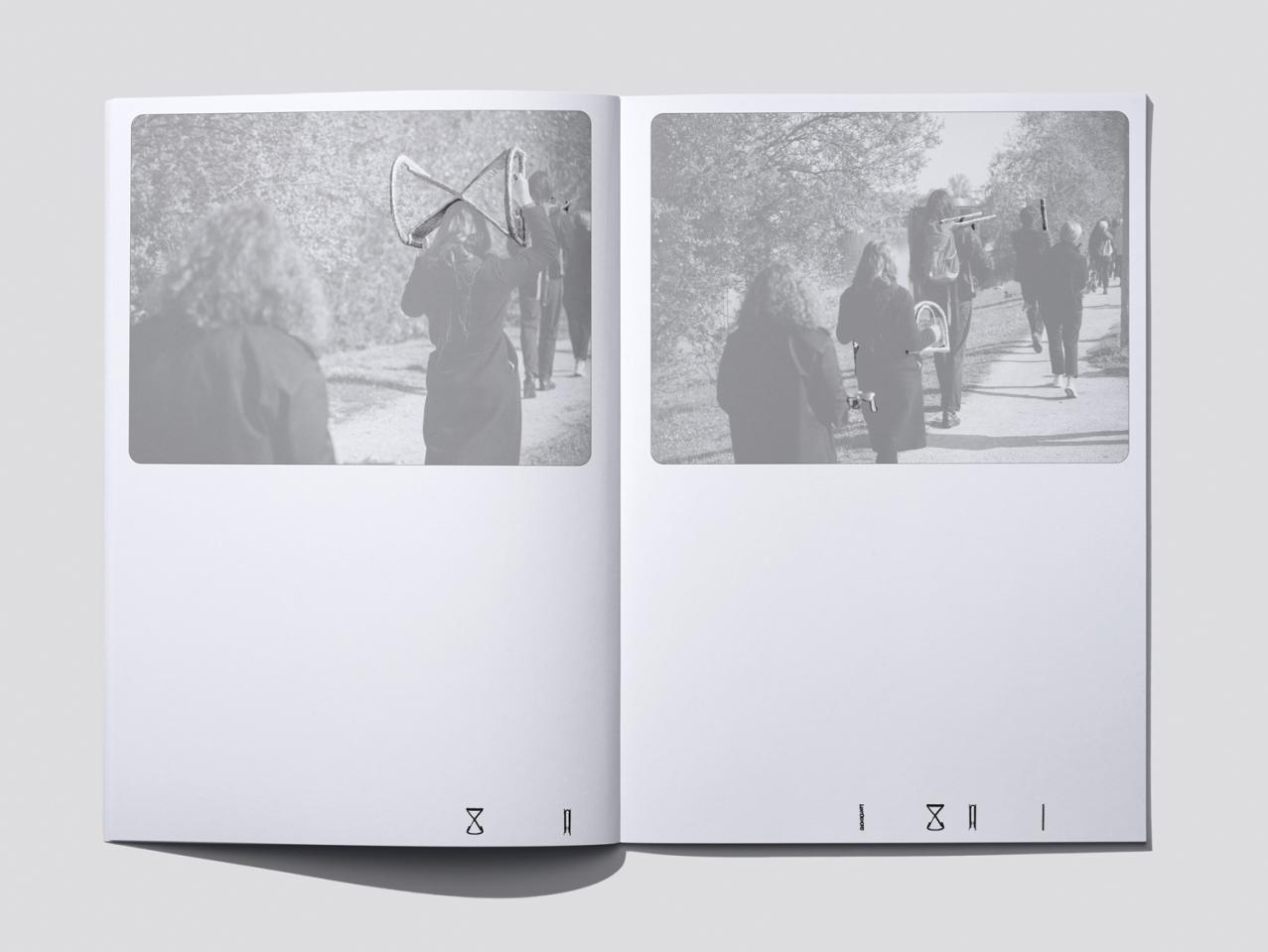

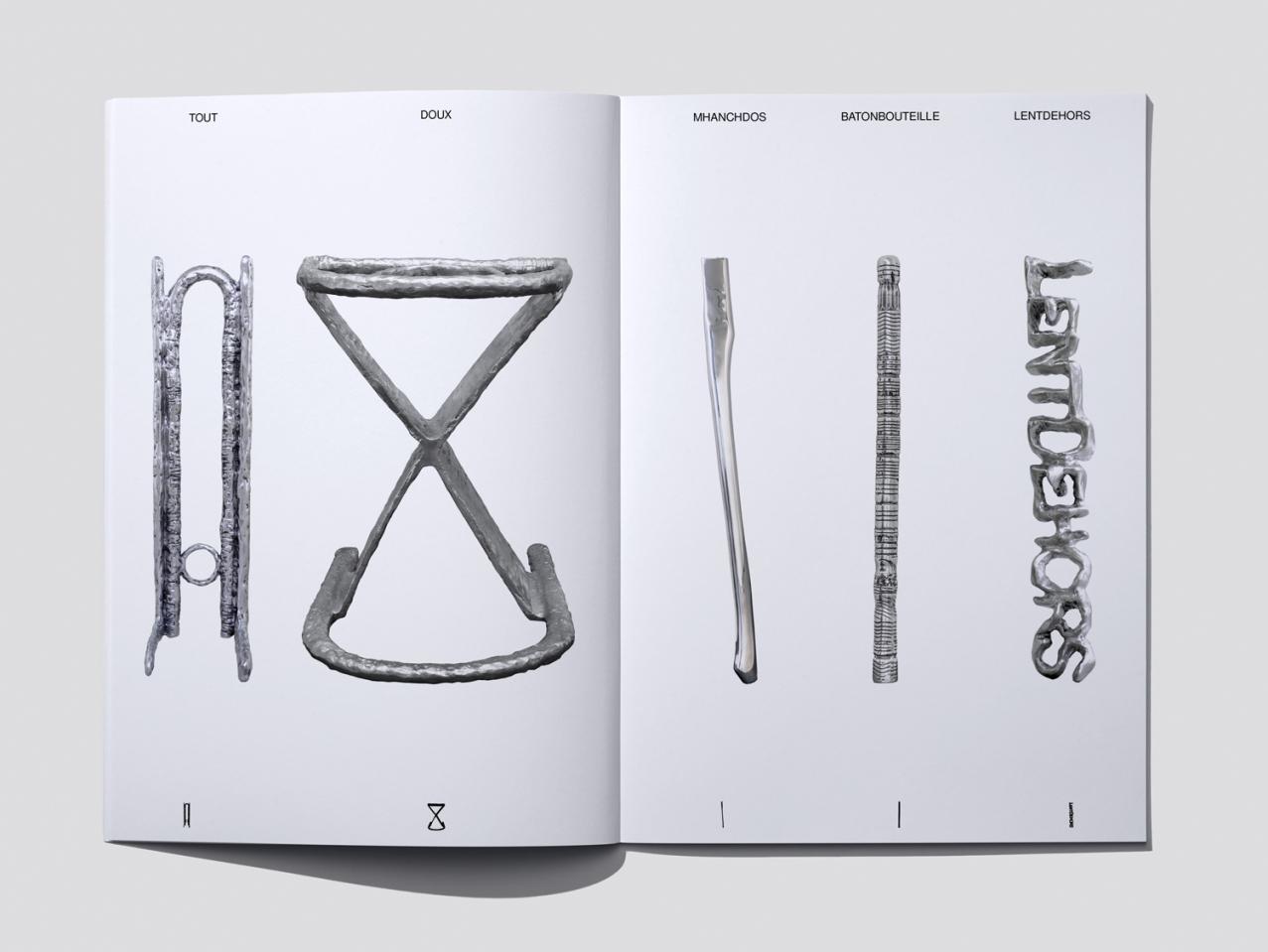

Once their final forms have been completed, then the sculptures can express themselves: they introduce themselves in exhibition texts5, or speak for themselves in the book Procession (2023). This writing process relates to another part of Émilie Perotto’s approach with the “Spécialistes de la Situation Sculpturale” [Specialists of the Sculptural Situation]. Her Manifeste de la situation sculpturale [Manifesto on the sculptural situation] formulates concepts that the artist has developed in the past few years, exploring new ways of viewing and presenting works of art. The “sculptural situation” defines sculpture as a tool that facilitates the meeting of a body, a space, and an object. Audience members are invited to take part in a sculptural situation when they sit on, handle or read the sculptures. Therefore, the sculpture is understood as a way of envisioning the physical space and relationships between people and the manners in which objects are produced and shown.

Far from the authoritatively guarded works of the “white cubes”, Émilie Perotto’s pieces encourage handling. This was notably the case for her exhibition VOLONTAIRE at the FRAC Poitou-Charentes in 2020. The manufacturing of her sculpture TAKE CARE (2018-2020), for instance, was entrusted to a foundry, and the processes and decisions that birthed it happened far from the artist, during a period that she had no intention of overseeing. The aim was to propose a piece that looked fragile and vulnerable, at odds with the material it was made out of — steel. TAKE CARE prompts visitors to notice the space around them. They are invited to touch it, to take its title into consideration, to literally take care of it — this network of care having started beforehand during the piece’s lengthy and shared creative process.

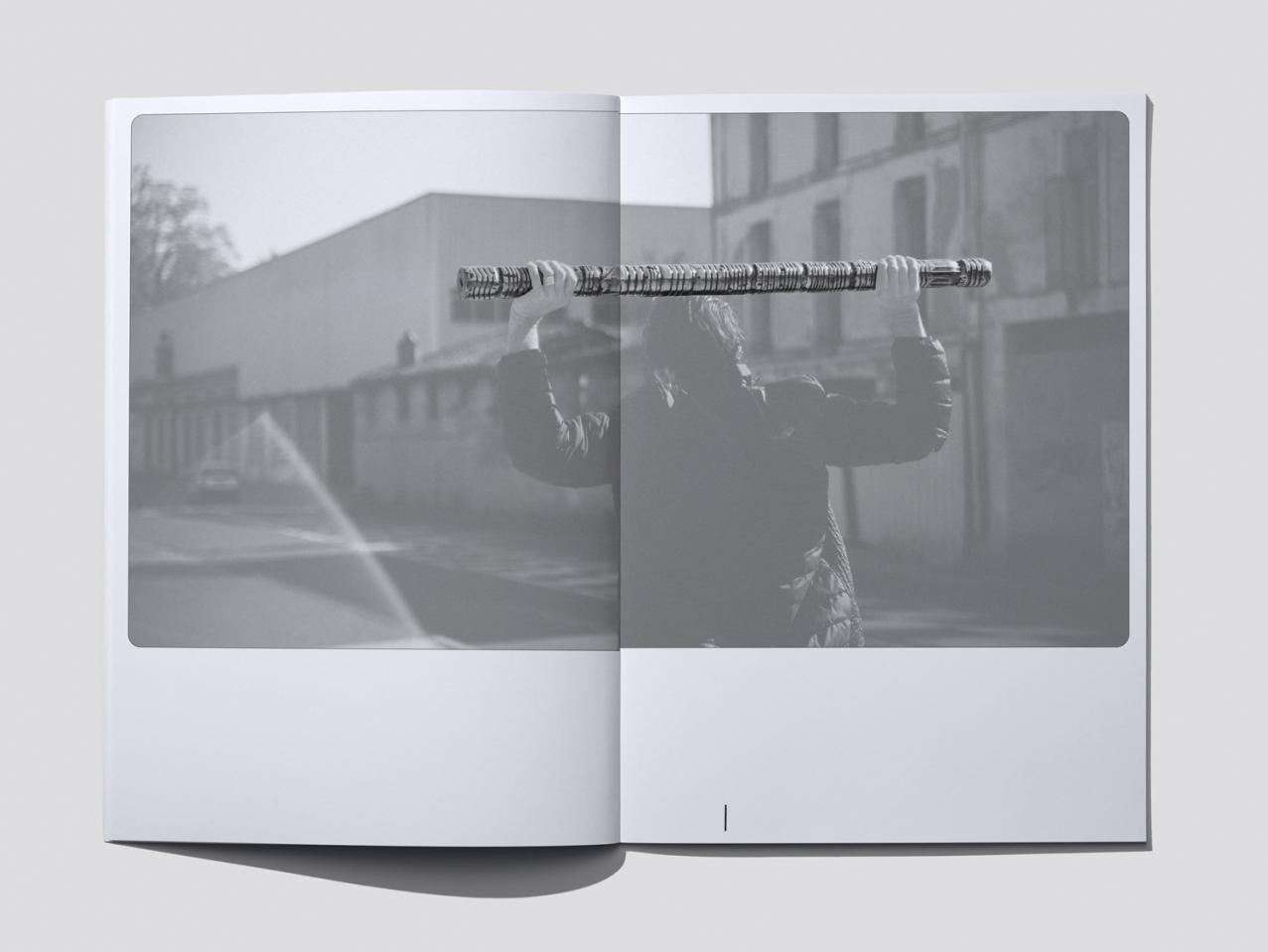

In the same exhibition, Émilie Perotto also showed DILIGENCE (2018-2020), a sculpture that refers both to the means of transport and to the term “diligence”, in the sense of “careful and steady”. As is often the case, this piece is the result of a multi-step process that took place in several locations in France. All of the travelling that the project involved was achieved aboard a contemporary form of “diligence”: via a website that enables private individuals to move parcels. The sculpture, which was transported without packaging or insurance, therefore became a vehicle for relationships, an intermediary. Because it went through a large number of steps and hands, it makes perfect sense why the work would be considered a “project”6. From the artist’s perspective, sculpting does not equate making objects and, should the result of the process be tangible, this result may well be far removed from the original intention. If some things don’t go as planned over the course of the manufacturing process, these alterations are in fact welcomed. Sculpture generates a desire to approach people who will enable it to exist and then be exhibited with no mention of this production process to the public: the piece carries its history and its nature as a project within it.

As a matter of fact, Émilie Perotto’s practice is almost akin to an architect’s work method. In her book Pesmes. Art de construire et engagement territorial, theoretician Émeline Curien defines the relationship between some architects as the sharing of a skillset — a definition perfectly applicable to Émilie Perotto’s work process: “Because it retains the trace of the human hand, [handicraft] is viewed as a possibility to invest meaning into the construction. A number of [architects seeks to] invent other forms of relations to the building site and to its social, economic and political implications: to take part in the building process, in partnership with the tradespeople, by becoming involved in the construction structures.7” When she worked on the Moly-Sabata commission À cœur vaillant [Brave of Heart, 2016], Émilie Perotto acted as project manager in collaboration with partner companies, combining industrial methods and the expertise of craftspeople. À cœur vaillant [Brave of Heart] is made with local granite. After having selected her rocks at the quarry, Émilie Perotto sent them to an apprenticeship centre to have them rough-hewn — a process during which the raw blocks are rid of any “excess”. She then decided how they would be positioned on the ground, suggesting a variety of interpretations: the layout of the rocks, which form an autonomous set, may give the impression of being arranged haphazardly, like a children’s game or a seating area.

One of the most striking aspects of Émilie Perotto’s practice is that it doesn’t limit itself to using material mediums and production techniques, but also includes a theoretical dimension that is constantly being questioned. What, indeed, defines a creative authority’s status? Is it their way of working, of communicating, or is it how their projects are exhibited? Through her ever-evolving research, Émilie Perotto opens up a field of possibilities and a reflection on the nature of the art object and the position of the artist.

Translation by Lucy Pons, 2024

Notes :

1. The author in conversation with the artist, Paris, 11 January 2024.

2. In reality, her action is more drawn out in time, since she also supervises the sculptures manufacturing process, among other aspects.

3. 06 15 2010 47° 21’ 38N 3° 23’ 6E, 2010. This sculpture was conceived, produced and permanently installed during a residency with ironwork students from the Mont Châtelet vocational college in Varzy (Pierre Cluzel, Sylvain Dechaume, Nicolas Deléchenault, Dimitri Dieudonné, Clément Fouley, Camille Freret, Jonathan Heurgué, Xavier Karger, Émilie Kowalscyk, Kenny Lofel, Cyr-José Meira, Brice Minana, Quentin Morisset, Clément Tartar).

4. ABSENCE TEMPORAIRE, signed “Situation Sculpturale Service”, 2020.

5. VOLONTAIRE exhibition, Frac Poitou-Charentes, 2020.

6. And that it should remain as such even in its final form — similarly to how, in the field of architecture, the term “project” also designates the completed building.

7. Curien Émeline, Pesmes. Art de construire et engagement territorial, p. 22.

Cast steel, produced by the Focast Foundry, 3 different copies, 123 x 47 x 40 cm and 90 x 55 x 41 cm

View of the exhibition VOLONTAIRE, FRAC Poitou-Charentes, Angoulême, 2020

Photo : © Romain Darnaud

Cast cupro-aluminium, 120 x 20 x 20 cm

View of the exhibition VOLONTAIRE, FRAC Poitou-Charentes, Angoulême, 2020

Photo : © Romain Darnaud

Granite, 135 x 230 x 120 cm

Sculpture produced by Ghislain Bouchard, Montalieu-Varcieu apprenticeship centre, on the occasion of the exhibition Les épis Girardon, Moly-Sabata, Sablons

Metal, 325 x 430 x 300 cm

Parc Saint-Léger Art Centre, off-site programme.

The sculpture was conceived, produced and permanently installed during a residency with ironwork students from the Mont Châtelet vocational college in Varzy.