The Tall Ugly Woman and the Long-Haired Lumberjack

The Tall Ugly Woman and the Long-Haired Lumberjack

A written fable based on three works selected by the author in the Documents d'artistes Bretagne collection

One day, a tall ugly woman wearing a petrol blue coverall with lots of pockets met a lumberjack with long red hair while she was walking in a wood. It was a Tuesday, her weekly day off for the woman who worked in a service station at the entrance to a motorway. The woman was poor, she kept her work clothes on even when she wasn’t busying about between the petrol pump, the cash register, and the tyre pump on wheels, which customers systematically forgot to put back where it belonged after using it.

There was a barely veiled sun which was thrusting its rays between the branches of the trees like long, thin, white fingers. The lumberjack was taking a break, sitting on a stump that was still warm from his saw, from which you could see sap dripping down. He had a can of Coca Zero in one hand and, in the other, he held the handle of his chainsaw with the same tight grip as the owner of a fighting dog. From his helmet protruded large thick locks the colour of carrots, held in place by two protective earmuffs made of green plastic.

The lumberjack did not hear the tall ugly woman approaching. He suddenly saw a pair of muddy boots intrude into his field of vision from the side. Looking up, he saw a huge blue shape rising upwards from those boots, and moving with all the elegance of a bear. A small round head, framed by two plaits joined together by an elastic band at the top, completed the silhouette. The whole figure looked like an exclamation mark upside down.

“Hallo, I’m looking for the Cabin of Mystery, can you help me?”, said the exclamation mark.

Taking his time, the lumberjack carefully stood the can of Coke on the stump, before launching into his directions.

“You follow this track for about 500 yards. Then you’ll come to a small clearing with a picnic area. You cross the clearing, still keeping straight ahead. At the end of the track, near the picnic area rubbish bins, you’ll see two tracks. You take the right-hand one. There’s a big oak tree, you can’t miss it. About 200 yards further on, you’ll come to another fork. This time you take the left-hand track, which climbs a little. You follow it until you see a path on your right. Make sure you don’t miss it, there’s a clump of hazelnut trees hiding the sign. You take that path, it’ll bring you right to the Cabin. D’you want me to draw a map?”

“No, I’d rather you came with me”, said the woman scratching her cheek. “I see you’ve finished chopping down this poor tree. Don’t you think it would be good for you to stretch your legs before you cut the next tree down?”

This woman isn’t afraid of anything, thought the lumberjack, used to scaring away any people he came across walking in the woods. Joggers in particular, who often got lost in the forest, and looked terrified when they came upon him by chance in a copse. It is true that with his high density polypropylene helmet and its mesh visor, his forester’s jacket with its fluorescent stripes, even more serried on the shoulders, his gloves with their padded palms and thumbs, and his two-stroke chainsaw with its multi-cut chain, he looked more like a Sengoku warrior than a forester.

“Well, why not? Can you wait just a second?”, said the lumberjack, taking off his helmet, before going to open the boot of a Subaru 4x4 parked a short way off, and loading his gear into it.

His mane of hair, now unleashed, fell like an iron curtain onto his shoulders. He shook it free of the chips of wood lodged in it. It was a magnificent sight, and you could feel that he was well aware of the effect it made.

“What’s that?”, asked the women, pointing at the sides of the Subaru.

On each of the four wings were affixed wooden boards seeming to act as wheel covers, looking like chalet shutters. Drawing closer, the woman saw that they were kitchen cupboard doors. Old-fashioned, rustic-looking doors, made of dyed oak, with wrought mouldings—a reminder of kitchens of yesteryear, large Sunday tables set for many, and meals lovingly prepared by the old folk.

“That’s because of the boar”, said the lumberjack. “For a while now I don’t know what’s got into them, they’re totally crazy. Last week one of them charged my jeep when I was having a snack behind a mound. I heard nothing, I had my helmet over my ears. It attacked the wheel, the tyre was completely wrecked. One of my colleagues had the same problem, a month ago. They don’t touch the rest of the vehicle, they go straight for the tyres. It seems they’re attracted by the smell of warm rubber. They’ve developed a taste for it from feeding on tips, near allotments. A hunter friend told me that he found a barely crumpled plastic bag in the belly of an old male hog. It must have swallowed it whole. You could see the Carrefour sign quite clearly. Terrible, isn’t it? Since then I’ve been protecting my wheels, and I cover my tyres with a repellent liquid. Half a litre of water, half a litre of white vinegar, and a few drops of washing-up liquid. That works a treat with weasels, so why not with wild boar? My sister gave me the boards. She works at a Mobalpa kitchen shop. They’re made of 19mm multi-layer high pressure laminate. Models from the Timeless Trends line. These have slight flaws in the wood, where they’re glued, so they can’t be sold. But they’re perfect for my wheels. Nothing less than boar-bucklers!”

And the lumberjack shook his lovely mane of red hair by way of conclusion.

“Mad!”, said the woman.

She wasn’t expecting a lumberjack to be so talkative. In the stories she’d read as a child, they were always rough, strong-silent men, with beards and plaid shirts, who said Holy cow in a weird accent when they were annoyed, and were unmoved by the tears of trees when they felled them.

Once all his things were stashed in the jeep, the lumberjack and the woman walked into the forest along a track. They walked side by side, but not at the same level. The lumberjack plodded heavily along in one of the ruts in the track, while the woman chose the raised grassy strip in the middle, so as not to dirty her boots any more. As a result, she was two good heads taller than the lumberjack. From time to time a stone would throw her off balance, and she brushed against his shoulder, before quickly regaining her equilibrium. On one occasion, absorbed by looking at an erratic block of rock beside the track, she even fell. He offered her his hand to pull her back up, and she graciously but blushingly accepted.

While the lumberjack explained to her in detail the financial problems of the Union of Woodworkers, which he belonged to, and whose secretary had recently skedaddled with the money—it took the lumberjack a long time—, the woman looked at her companion’s forearms, swinging to and fro in time with his footsteps. From wrist to elbow, not a square inch that wasn’t covered with tattoos. A dragon spitting green flames, two swans forming a heart with their necks, flowers being foraged by a swarm of multicoloured butterflies, a chameleon catching a fly with its vermilion tongue, a mermaid with a huge head of purple hair hiding the nipples of her breasts. Lots of twisting curves, very few right angles.

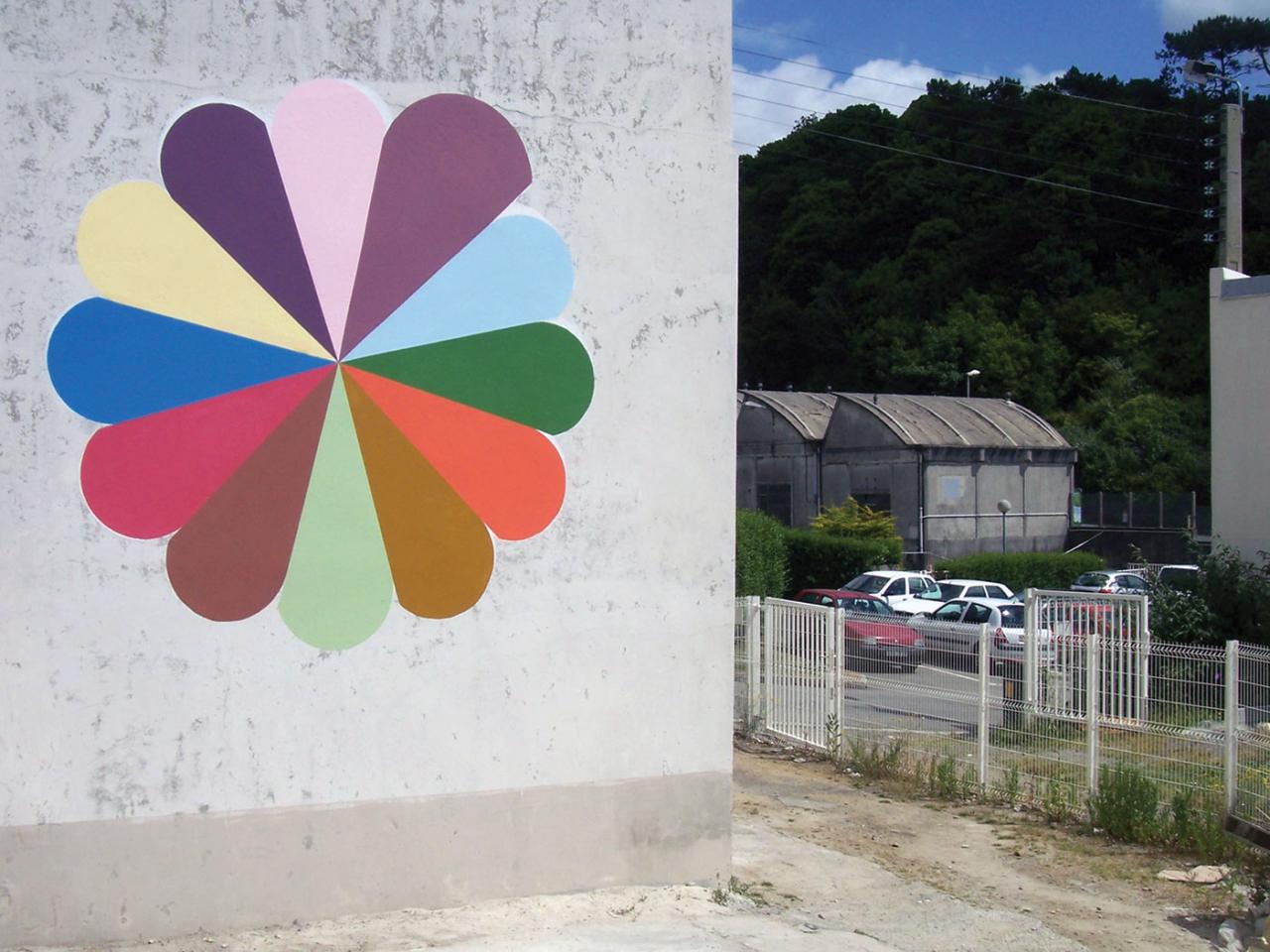

In the midst of these interlaced designs the woman suddenly noticed an abstract motif just beside that bone which forms a small lump above the wrist, precisely where put a stamp on you that allows you into nightclubs. It looked like a daisy with twelve petals drawn on Illustrator, except that there was no pistil, and the petals were not white but all in different colours. Something between the big wheel in TV games and a logo for a brand of yoghurt or ice cream. The tattoo was not much bigger than a watch dial, but it stood out in the middle of all those exotic creatures.

“That’s all very nice”, said the tall woman to try and change the subject—trade union stories didn’t interest her.

She leaned forward to touch the tattoo on the lumberjack’s wrist with her finger; taken by surprise, he jumped back like a scared horse.

“Ah, so you like them? I chose the colours myself, I wanted slightly muted shades, mint green, petrol blue, aubergine, putty. To make a change from my old tattoos, which I find too garish. Today I want to cover them all up. Or else I’ll write Errors of youth on them!”

The lumberjack rolled up the right sleeve of his shirt as far as his shoulder.

“Look, at the time I even had Pamela Anderson’s barbed wire tattooed on me around my biceps! I turned that into a Cosmic Serpent last year. It was a lot of work for my tattooer. And for me it made me question things a lot.”

With those words, the lumberjack burst into laughter, which shook his fine mane of hair again.

“Oh yes, it’s original! I’d never dare do it myself, I’m too afraid of needles. Just having a blood test makes me swoon”, said the woman, looking closely at the snake’s scales growing alarmingly in size when the lumberjack flexed his biceps.

You would really have thought the snake was alive.

They reached the clearing and sat down on one of the benches in the picnic area. The lumberjack told the woman that his name was Audemar, but that ever since he was very young his family and his friends nicknamed him Red Mane. The woman told the lumberjack that her parents had christened her Tamara, but that ever since she set foot in school everyone called her Taquet.

“Oh, why Taquet?”, asked the lumberjack.

“Because where I come from it means ugly girl, replied the woman.”

“But you’re not ugly at all!”, exclaimed the lumberjack.

“You’re really quite charming”, sighed the woman.

Then in her turn she embarked on a long tirade, describing in detail the suffering caused by her great height, combined with her shape, like a bottle of Perrier water. The whole effect contrasted not very flatteringly with her pin head and its imposing nose—at least that’s what most people thought.

“The architect who designed me got the proportions a bit wrong”, said the woman, laughing.

Then she explained how she had regained self-confidence thanks to a course about her inner child, a child she had stifled beneath thick layers of denial for years, and which had to be brought back to the surface, to breathe new life into her—the better to face the future hand-in-hand with it. This is what she had been taught by a fitness coach, who had very soft manicured hands, smelling of argan oil.

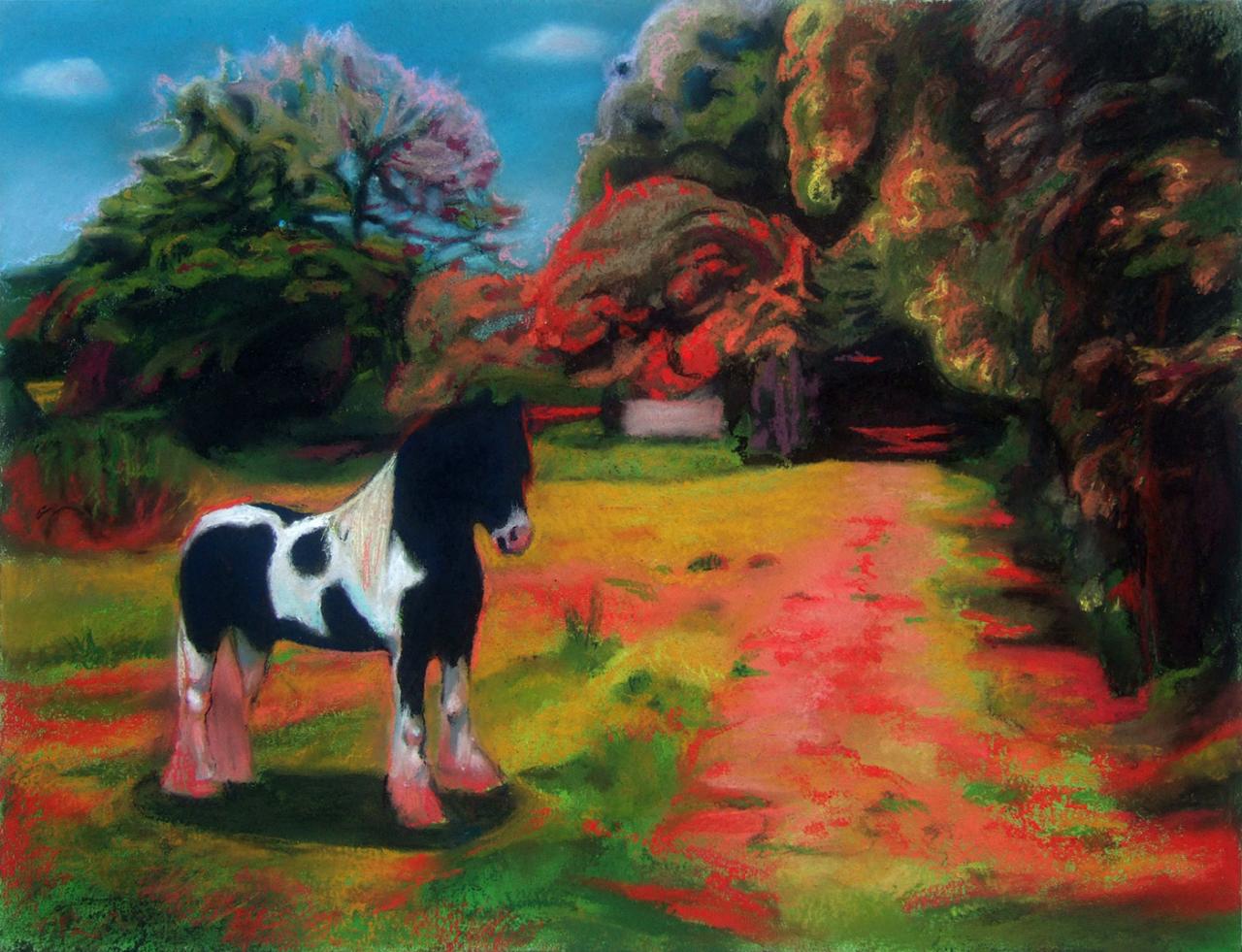

The woman was in the middle of explaining The 4 stages for becoming more efficient and optimizing the self-image, when she suddenly stopped. At the edge of the clearing, near the track leading to the Cabin of Mystery, a two-coloured creature was coming towards them. To start with the woman thought it was a cow. But the animal’s swaying gait and its large mane then made her realize her mistake: it was a magnificent pony with a piebald coat. It trotted towards them before stopping a dozen yards from their bench, then it stared at them both with its large globe-like eyes. The animal’s head was completely black with just the end of its muzzle white, as if it had been dipped into a bowl of milk. Its nostrils quivered, making regular little noises created by exhaled air.

“Hallo Mimosa”, said the lumberjack.

“Mimosa?” said the woman.

“Yes, this is Mimosa, Mrs. Crettaz’s pony… she’s a retired schoolteacher who lives in the next valley, said the lumberjack. He’s always escaping from his enclosure. Mrs. Crettaz spends her life driving all over the region in her Jeep to find him.”

“He reminds me of My Little Pony that I used to play with when I was young”, said the woman.

“Ah, so you had a pony too?” said the lumberjack.

“No, not a real pony, but one of these plastic toys, you know, with long pink and purple manes that children combed like Barbie dolls.”

“No, I don’t remember them”, said the lumberjack.

“Of course you do”, said the woman, “there was even a comic strip, don’t you remember?”

“No, I really don’t. All I had was wooden toys”, said the lumberjack.

“But didn’t you have a sister? or a female cousin? or a girlfriend who played with a pony?”

“No, we were six boys at home, with no TV. And the village school wasn’t mixed. Girls went in through the door on the right, boys on the left. You couldn’t get it wrong, the words GIRLS and BOYS were carved on the pediments above the doors. Those were different times.”

The pony was watching them, motionless, standing bolt upright, hooves covered with long white hair, like paint brushes. The woman found that he had something of a female country singer about him, a singer wearing tasseled boots. She got up to stroke him. The pony stepped back a few paces, then started to gallop, before disappearing for good into the wood.

“He’s afraid of strangers”, the lumberjack said.

“Doesn’t matter, said the woman, he made a very nice sight.”

She stared into the copse which the pony had trotted off through, as if she were going to be able to make him re-appear, just through staring. The pony didn’t come back. So she pulled out a Bounty from one of the pockets in her blue coverall.

“Would you like half?”

“Oh yes please”, said the lumberjack.

The woman broke the chocolate bar in two and gave him the larger half, the part where the coconut formed a little white pile, curving outwards.

They set off along the track again, each in their place. The lumberjack in the rut on the right, the woman on the grassy area in the middle, still two heads taller than him. They talked about everything and nothing. The woman said: “Oh yes! No…? Really? Is that so? When the lumberjack spoke, to indicate that she was following the conversation. The lumberjack, for his part, saved his saliva when it wasn’t his turn to talk. They soon arrived at the last path, the one whose sign was hidden by a clump of hazelnut trees.

“We’re nearly there, it’s that way”, said the lumberjack. “Come to think of it, why do you want to see this cabin?”

“It’s for a family party, said the woman. Every year, one of my cousins invites all the others for St. Nicolas’s day. We call it a cousins’ get-together. Because there are lots of cousins, we look for halls to rent. Or forest cabins. This year it’s my turn. One of the customers at the gas station where I work told me about the Cabin of Mystery. Because I had nothing planned for today, I said to myself it would be a good idea to visit it.”

“You’ll be disappointed, it’s very small”, said the lumberjack. “You can hardly fit eight people inside, if that. And everyone has to stay standing!”

“Oh heck, that won’t do, but I’d still like to see what it looks like”, said the woman.

The cabin was in fact very small, but in good order. The woman stooped and pressed her forehead against one of the windows to see inside. She saw a large table covered with a wax cloth with little red and white squares, seven chairs with straw seats, a wood-burning stove, plates and crockery on a shelf, and an oil lamp hanging in the middle of the room. Putting her hands on her forehead to make a shield, she could also make out, at the back of the room, fixed equidistant from each other, seven hooks made with stuffed deers’ feet all in the same position, like a finger beckoning: Hey you, come this way a bit!

“They don’t need Snow White here, everything’s just so impeccable”, said the woman, chuckling.

“Yes, the members of the Youth Club which owns the cabin are sticklers about tidiness and cleanliness”, said the lumberjack. “When you rent the place, you’d better be sure and hand it over in the same state you found it in, or else there’ll be trouble.”

The woman and the lumberjack sat down on a log bench in front of the cabin to share a second Bounty—this time she kept the bigger half for herself—, then they set off to go back to the Subaru. He was beginning to get late, the trees made long tapering shadows like organ pipes.

By the car’s boot, they shook hands for a long time before taking their leave of each other. From all of her six feet, the woman could admire the top of the lumberjack’s head, especially the swirl from which his splendid red locks sprang. A spiral of fire, thought the woman, who refrained from kissing that spot. That was the last thing she saw of him.

Weeks passed, the tall ugly woman filled up gas-tanks, cleaned windscreens, and put air in tyres. Thanks to another customer, she managed to rent a multipurpose hall which could accommodate more than 60 people, sitting, for her cousins’ get-together. It was a great success, and she scored points among all her cousins. But in her lonely moments, the tall ugly woman often thought of the lumberjack and his magnificent head of hair. Several times she went back to the place where they had met, and took the track leading to the cabin; she made inquiries at the local office of the Union of Woodworkers, wrote a letter to the secretary of the Youth Club, and looked in the directory for Mrs. Crettaz’s address and phone number. All in vain. Nobody had ever heard of him. She started to wonder if he even existed. I must have been dreaming, the tall ugly woman tried to persuade herself, putting on a new coverall, this time rust-coloured, like a sea urchin. She did her utmost not to think about him any more, and called her fitness coach.

One day, when she was getting ready to smoke a cigarette near the car wash—that was where she usually took her break, because over there nobody would bother her—, she discovered something that left her paralyzed for at least five minutes.

On the outer wall of the gas station, the one behind which the vacuum cleaners were stored, someone had painted a large motif which looked like a daisy, but without any pistil, and with the petals all in different colours. The tall ugly woman counted them carefully, clockwise. There were twelve, just like on the lumberjack’s wrist.

Translation : Simon Pleasance & Fronza Woods

A written fable based on three books selected by the author in the Documents d'artistes Bretagne collection :

Babeth Rambault, La Roue, 2014, photograph, 50 x 75 cm

Guillaume Pinard, Le Poney de Peillac, 2017, dry pastel on paper, 42 x 56 cm

Samir Mougas, Programme 1 RNB Design, 2008, wall painting, 350 x 350 cm

Photograph, 50 x 75 cm

Dry pastel on paper, 42 x 56 cm

Wall painting, 350 x 350 cm