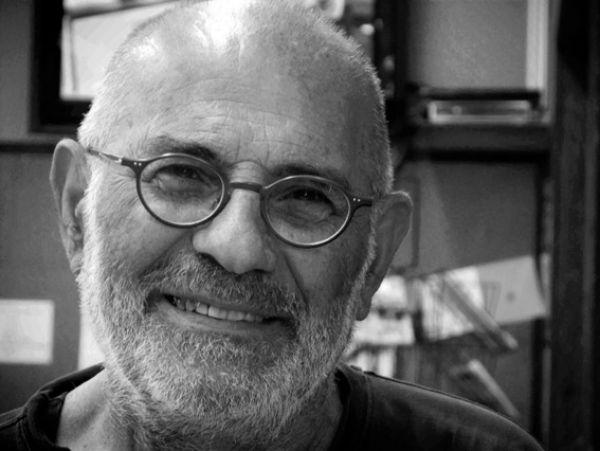

Rajak Ohanian

© Marion Ohanian

About 200 photographs taken during the gypsies' meetings at the Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, France

> watch series

Translated from French by Louise Jablonowska

From Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer to Chicago, through Sainte-Colombe-en-Auxois, Rajak Ohanian reflects upon his unique artistic journey of almost 60 years. With the sharpness and kindness that best describe him, he tells us about his personal relationship to photography and land, and gives us an insight into the community he has been building.

L.M-L. Looking at your work as a whole, the diversity of the subjects and places photographed stand out immediately. The notion of portrait however infiltrates the majority of the series (portraits of a village, a small business, key figures, towns, communities, landscapes...). There is also a recurring documentary procedure, which could be described as immersion or a relational process. In a way, ahead of time, you have invented an in-residence, self-organised and self-produced method of creation. For ‘Les fils du vent (Children of the wind)’ for example, the images are candid, but they result nevertheless from time spent with members of the gypsy community, from a relationship. How did you manage this?

R.O. The gypsies were friends, especially young people with whom I grew up in Décines. In 1958, I began accompanying them to Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer where they met in May every year. I lived with them and we had good times together. Of course I started to photograph this community that I was virtually part of ‘from within.’ Gypsies have always been rejected, but this has been exacerbated over time and the gatherings gradually became less festive. Back then they were heading up the Rhône Valley to look for work. I went to Saintes-Maries for ten years, and then the series came to an end because the petrol shortage in 1968 stopped me from making the trip.

For the portraits of key figures, some of them were friends, close friends, ‘extended family,’ and sometimes from encounters that I initiated. In the same way as other series, I had time requirements. It was important for me to spend some time with each of them to photograph them in their world.

About 200 black and white photographs

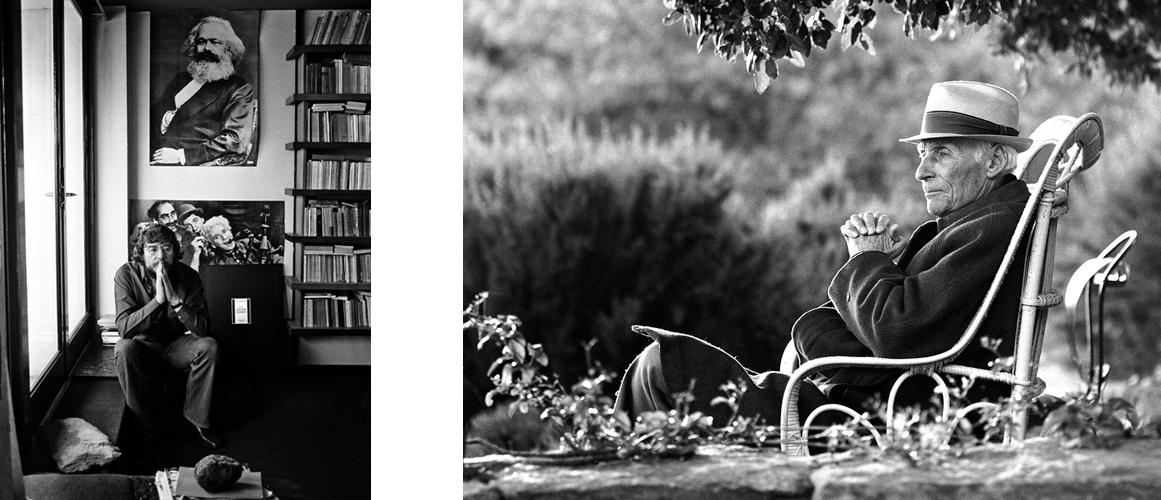

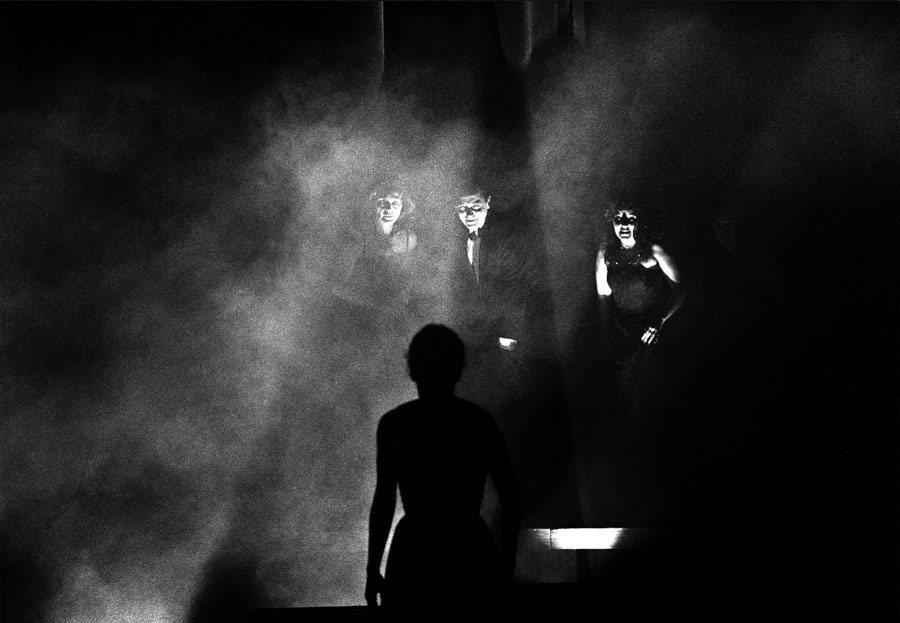

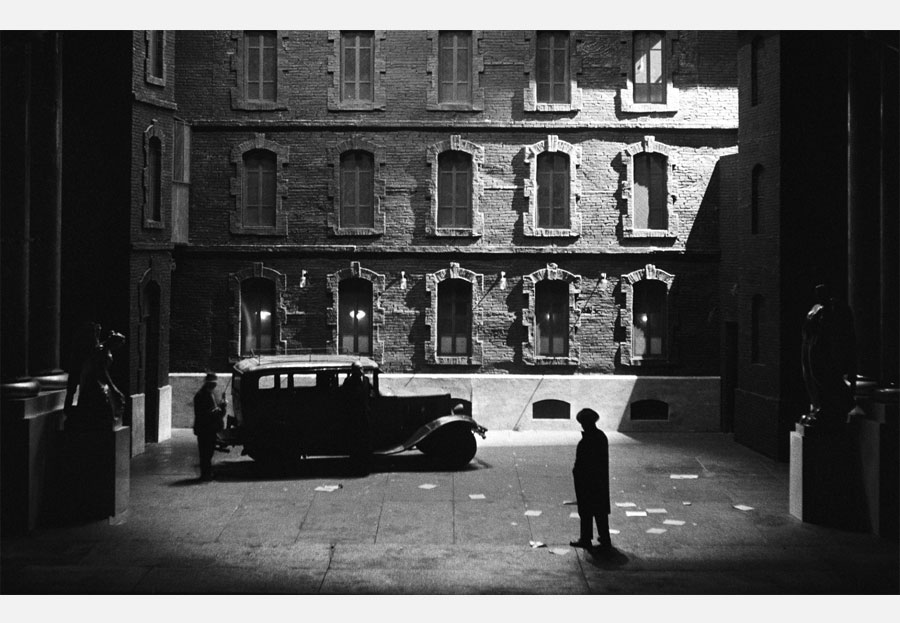

Roger Planchon and Bram Van Velde

> watch series

L.M-L. Alongside your personal work, you were a theatre photographer for a long time. Did this experience influence your positioning as an artist?

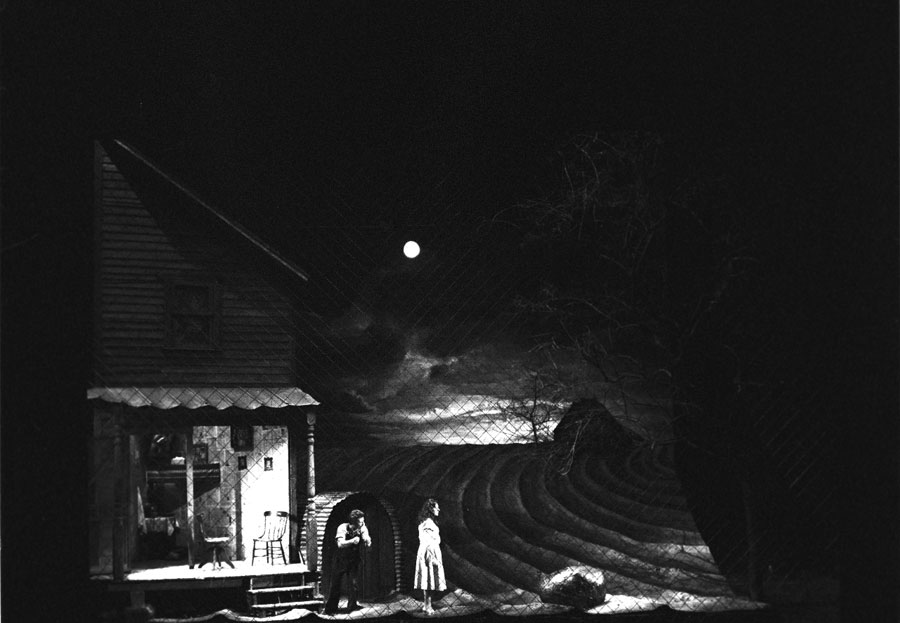

R.O. I did indeed work in theatre for years, in particular at the Théâtre National Populaire in Villeurbanne where I photographed performances by Roger Planchon. It was primarily bread and butter work, paid quite miserably for that matter. There were two different periods, to begin with a ‘systematic’ period during which I just used to record the performances, without any special consideration. Then there was a more precise period when I decided to build up a regular presence with the troupe. I attended readings and rehearsals to understand the construction of the pieces, to document the stage production and thus make the best decision regarding shots of the performance, in step with the writing.

L.M-L. Although this is a commissioned piece of work, connected to a specific context of replicated action, this transition is important to me in your way of perceiving the photographic act and taking a stand in relationship to the subject. We go from a technical recording of reality unfolding, to a more programmatic positioning, a form of writing or documentary protocol. And the principle of immersion mentioned earlier is also being implemented.

R.O. My contact with Roger Planchon made me reconsider my relationship with the territory. Planchon was a pioneer of decentralisation, before Malraux, he worked to make it effective. He called upon artists to take responsibility for working where they live and to show their work locally. He urged us to be stakeholders of our territory.

To go further

> Interview of Roger Planchon on the website of INA (National Institute of Audivisual)

With Roger Planchon, Isabelle Sadoyan, Jean Bouise.

R.O. When I stopped working for the theatre, it was a difficult time. I had to be hospitalised for heart problems and whilst convalescing, I took the decision to become involved in rural life. On French post-office and telecommunications calendars I looked for villages with the least inhabitants possible. The first on the list was the village of Sainte-Colombe-en-Auxois in Burgundy. I contacted the mayor to discuss my idea to live within the village for a while and he then convinced the 44 inhabitants to welcome me. I lived there for almost two years. I was determined to live there but not in the homes of the people. I therefore took over the abandoned school. I photographed village life and produced a portrait of each inhabitant. The first exhibition of this work took place in a village barn.

Quotidian life of the village, black and white photographs, 30 x 40 cm each

Portraits of the 44 inhabitants (Jean-Pierre Leblanc and Suzanne Flacelière)

Black and white photographs, 120 x 180 cm each

> watch series

Exhibition views, CRAC Languedoc-Roussillon, Sète, 2010

32 photographs, 165,5 cm x 131,5 cm each

Collection of Musée de l'histoire de l'immigration, Palais de la Porte Dorée, Paris

> watch series

L.M-L. The format of the 44 portraits of the inhabitants of Sainte-Colombe-en-Auxois is almost full-size, like for the series "Portrait of a small of medium-sized enterprise" where all the employees of a fabric company are photographed. For each series, in addition to the photography, you pay great attention to the choice of dimensions, the composition and the quality of the prints. At the start of your work, this concern for the format was quite unusual?

R.O. In fact, I have always considered the format in parallel with the shots. The most poignant example of my choice of composition was for À Chicago (In Chicago). I stayed in this city for several months and wanted to depict its verticality and rhythm. I implemented several photography protocols, like for example to take up position at point zero of the town, where the numbers of all the avenues begin; or take the same viewpoint from a skyscraper, showing an additional floor on each photo... All the images from each film are then printed on the same support, forming a very large format print. It’s not a contact sheet, but a meticulously chosen composition.

Exhibition views, Institut d'art contemporain, Villeurbanne, 2004

7 black and white photographs, 330 x 300 cm each

Photo : © André Morin

> watch series

L.M-L. Is this an allusion to cinema? I am thinking in particular of the documentary film "Numéro Zéro" by Jean Eustache, the length of which is determined by the limits of the recording medium.

R.O. I love cinema, but I am not particularly referring to it here. For me it is more of a relationship with painting and music. Moreover I was interested in music from a very young age, I would have liked to be a pianist. Around the age of 10 or 11, big health problems made me bedridden, so I took refuge in reading and music and that saved me.

I think I was also influenced by the fact that I specifically frequented painters at the start of my work. They chose their frames beforehand, which perhaps incited me to think about the dimensions of my images beforehand too. My long-term interest in painting forms the basis of my relationship with image, hence the large formats that I decided to use very early on. This was new to the world of photography and attracted much criticism and incomprehension.

L.M-L. There are other recent series where the framing and the composition are important and where the pictorial relationship is significant, these are portraits of landscapes or territory: ‘Metamorphoses I’ about the Breton shoreline, ‘Metamorphoses II’ in the Cévennes and ‘Portrait de l'esprit de la forêt (Portrait of the spirit of the forest).’

R.O. I’ve also formed a habit of specifying a format before starting a series for practical reasons, to determine the relevant equipment to take. I generally set off with a camera and a ‘field lab’ to produce prints on site.

For Metamorphoses, the feature that slices through the image was decided afterwards, but the idea came to me through a technical chance. The mobile developing station that I took calibrated the format of the prints so I recomposed large images with several medium-sized prints. This fragmentation interested me and I repeated it at the end through the line that aligns the eye and separates the image from a romantic or aesthetical relationship with the subject.

Series produced on the French Brittany coastline from 1991 to 1993

16 photographs on Baryte paper, 97 x 69 cm each

> watch series

Métamorphoses II

Series produced in the Cévennes from 2007 to 2009

21 inkjet printer photographs on Baryte paper, 97 x 69 cm each

> watch series

Portrait de l'esprit de la forêt

Ongoing series, started in 1992

Photographs on Baryte paper, 24 x 30 cm each

> watch series

L.M-L. You also have a keen interest in literature? Not only do many authors feature amongst your portraits, but there are also many texts written about your work.

R.O. I’ve made it a habit to commission a text from a different author for each series. A work of art becomes reality for me when it is materialised and displayed, but also when it is reformulated by language. I have often chosen the author for the unique view that he may have on my work.

Georges Goldfayn, who was part of the surrealist group in the Breton period, wrote about Portrait of the Spirit of the Forest, Roger Planchon for the series on the village of Sainte-Colombe because he was a farmer’s son. I asked Paul Boucher, a lawyer from Lyon who worked hard during the Algerian War, to write about the gypsies. For Metamorphoses I, I didn’t want a "Breton" text, so I asked Annie Le Brun whose writing I really like, but who is nonetheless of Breton origin...

Lecture of Richard Crevier

Recorded during the exhibition Portrait d’une PME, Le Rectangle, Lyon, 2004

L.M-L. All these people that you photographed and with whom you have had varying degrees of close relationships go on to develop a sort of community, at least a set of emotional concentric circles. Is this a form of family in the broadest sense of the term?

R.O. The notion of extended family goes back to my childhood in Décines where we led a great, wild life with the local kids. Families welcomed other people’s children for a snack; we had many parties and gatherings by the water. I learnt French in the street. My parents spoke very little about their past or the history of the Armenians, we only gleaned information by listening to adults discussing. The Armenians in Décines were clustered around the factories, in particular an artificial silk factory and a chemical factory. The different migrants lived together: Armenians; Italians; gypsies...

L.M-L. You are also very close to your children. The question of intellectual heritage is obvious, as we know that your two sons studied fine art and that each is developing his own documentary approach. It is also significant that your granddaughter was a mediator of your last exhibition at the Bullukian Foundation. The relationship with history and the question of transmission seem rooted in your family.

Melik produced the work ‘Red Memory’ for his exhibition ‘Stuttering’ at the CRAC Languedoc-Roussillon in Sète. It pays tribute to the sharp observation that you have passed down to him. In a way here he displays his work through the eyes of his father. There is also an allusion to his brother with a film about a music group produced by Vartan, shown directly on the television that he used for editing at the time.

This leads us to the inextricable relationship between your personal story and the historical context that your family is part of.

R.O. Indeed, the transmission begins on the basis of what my father experienced, Garo (Garabed) Ohanian. In 1915, during the genocide of Armenians, he was deported to Alep in Syria, where he lived in an orphanage with his brother Aram. He was about eleven years old.

During the winter of 2005-2006, I felt the need to go to Alep, in my father’s footsteps. I went there twice and spent six months there. It was a personal initiative at the beginning. I looked for the orphanage in which he apparently stayed, but no trace was to be found in any archives. One encounter nonetheless led me to a district in which there would have been thirteen orphanages but no longer existed. I photographed this district and other places in the town that my father may have seen as a child. I also scoured symbolic places like the grottos around the Euphrate where the deported were contained.

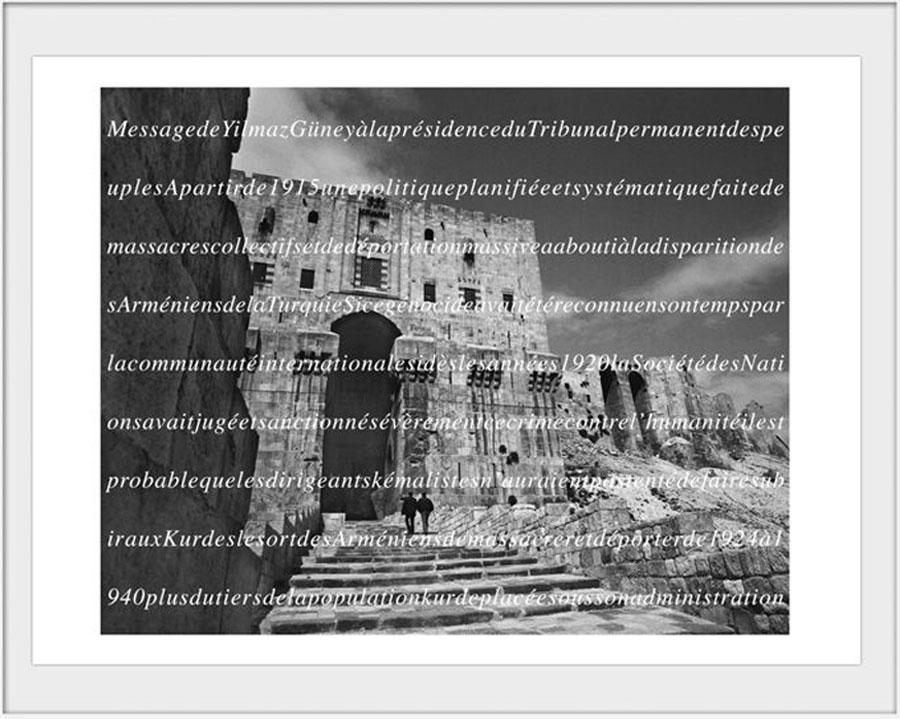

So I brought back these images that capture personal as well as shared history. I made the decision not to reveal them directly, by superimposing texts regarding the genocide of Armenians. The series is called Alep, 1915... Témoignages (Testimonies), but the texts are not accounts by Armenians who experienced genocide. I wanted to mark a distance regarding the events, by choosing texts by philosophers, historians, specialists whose credibility is well established (Yves Ternon, Emmanuel Levinas, Pierre Vidal-Naquet, Mustafa Kemal...), extracts from historical documents or from reports from the embassies of countries that were neutral or committed on the Turkish side during the First World War.

These white superimposed texts span the images and restrict interpretation. The hindrance is intensified by my desire to remove the spaces and punctuation. This barrier to deciphering reflects Turkish denial and the difficulty in qualifying events. The question of language is extremely important, before the term "genocide" was recognised we spoke of "massacre". The critical distance that seemed essential to me to put in this work unfolds both in the choice of the authors and in the non-illustrative relationship between the images and the account.

‘Something that requires an effort belongs to you more.’ This saying has always seemed relevant to me and could apply generally speaking to my way of working.

Series produced in 2005-2006

14 inkjet printer photographs on Vélin d'Arches paper

> watch series

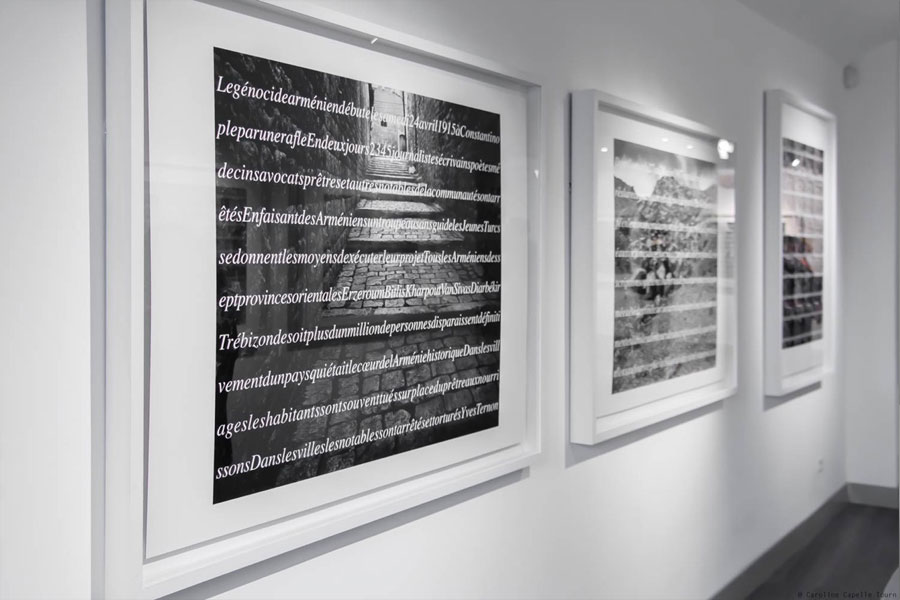

Exhibition views of Alep, 1915… Témoignages, Fondation Bullukian, Lyon, 2015

Exhibition produced by Bibliothèque Municipale de Lyon, with Fondation Bullukian and Centre National de la Mémoire Arménienne.

About the exhibition

> website of Bibliothèque Municipale Lyon

Les Portraits de Rhône-Alpes Matin, march 2015

Interview of Rajak Ohanian on France 3 Rhône-Alpes