Valérie Horwitz

Mine, Yours, Theirs

Valérie Horwitz’s work appears to originate in a fissure, subsequently lodging itself in interstices. Never quite similar nor quite the same, her practice can be understood as an embodiment of “the in-between” – between day and night, between light and darkness, between inner and outward lives. Forces – a wide range of them – are also in question, expressed according to the patterns and relationships that occur between physical and mental spaces. The constraint that underpins this force is vibratory in the way it shapes the image it depicts: entrapment of the body, incarceration, social determinisms – there is always present an attempt to reveal the invisible or, on the contrary, to capture existence in order to make it visible. That is to say, “to produce counter-information so that it may combat watchwords”. Social heritages, intimate traumas: for Valérie Horwitz, photography is both a formal tool and an anthropological witness. All of her work seems to anticipate the systematic blurring of boundaries between the two. While her work is often based on a protocol-based, methodological approach borrowed from social sciences, it also uses sensuality and movement as impressions of an odyssey of imprisonment.

With the film 5 Years (an interval) 2018, photography may for example serve to keep illness in check, to capture it, to trap it inside a frame like a species observed under a microscope slide; but it also becomes a craggy, atrophied and mangled landscape that screams “the impermanence of things”. Hunting down illness like a beast – as the disease evolves undercover, the body, truncated and removed from its image, dwells in the shadows in the here and now. Between half-light and naturalness, a hand reaching out through the void appears again and again like a leitmotiv: but does that hand heal or take away? In the pictures, it makes way for lush and profuse vegetation, and these pictures collide into one another.

In 2009, after being diagnosed with a medical condition that forced her into a period of isolation, the artist began to record her reality, coming face to face with her own body. Not always the body itself, but the presence of the body as suggested by an object: here a chair, there a body that has vanished – removed, subtracted from itself. The film, which is edited like a slideshow, produces substitutes of vague bodies, blue-tinged lifelines that must be recorded and consistently contained. Devised as an installation, the film is meant to be viewed in an intimate setting, hence the presence of a single chair.

As long as “memory is built upon wounds”, as Derrida put it, pain allows us to exist within the world in a way that leads us to experience life through the permeability of its environments. In 2018, a series of pictures crystallised the traces of the diagnosis: “the medication poisons the body and aggravates the illness”, she writes. These self-portraits are used as mediums to connect with specialists at the Salpêtrière Hospital. Ultimately, only one picture endures, which likewise challenges a certain discourse and the radicality of an assertive practice: a solitary back, devoid of any limbs, shines an almost abstract light on the stigmata of disease.

While the artist has been using various mediums daily since 2009, she has chosen to not limit herself to anything specific: photography, archive images, poetic writing – each project determines her formal requirements and specificities.

For Peines mineures [Minor Sentences], constricted space is subjected to further rules. At the Baumettes women’s detention centre in Marseille, portraits marked by incarceration are painted through dialogue. Deprived of their freedom and constrained by space, these women gradually let words flow more freely. At first there is waiting, but then the camera triggers something, the artist explains.

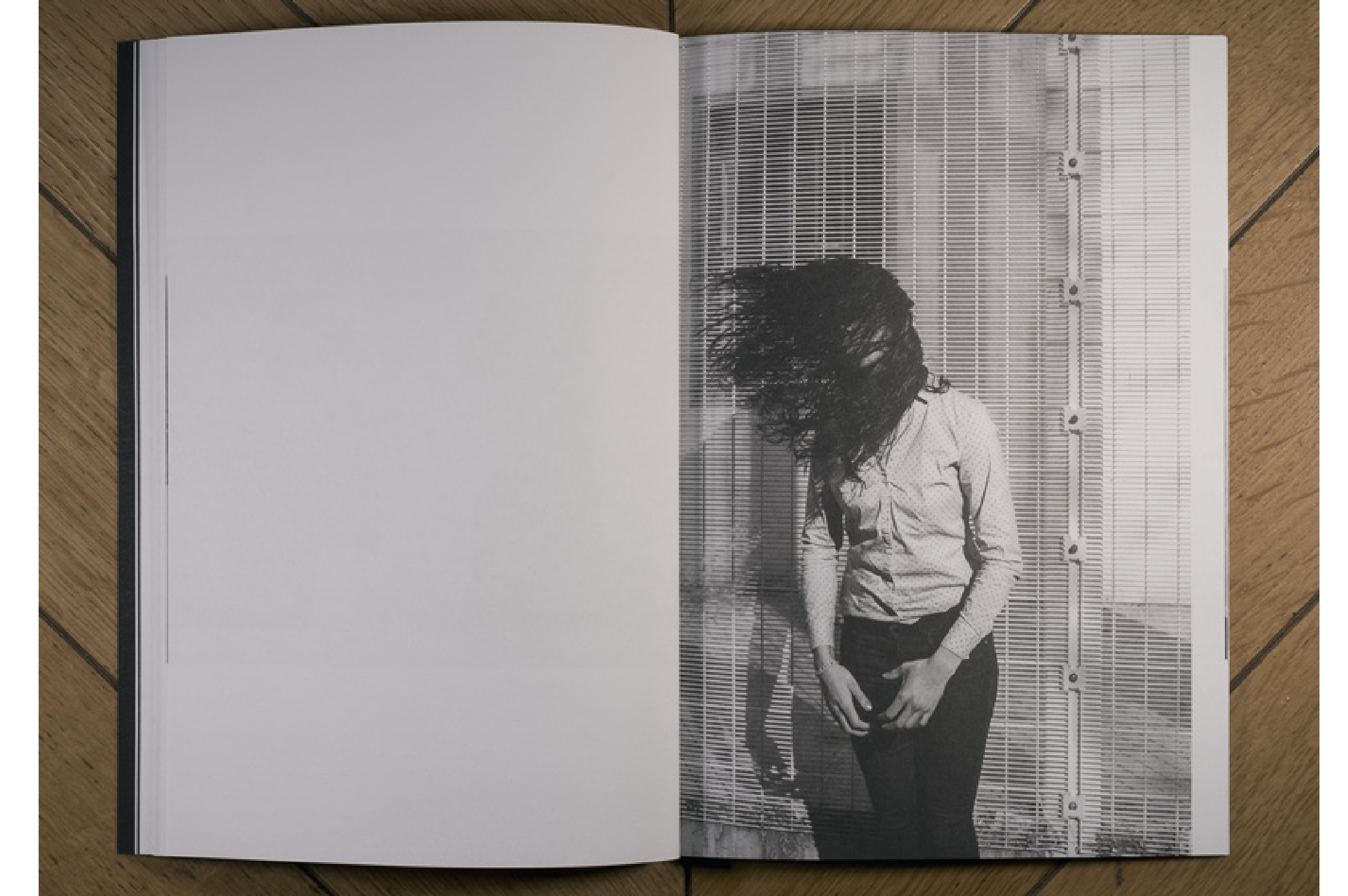

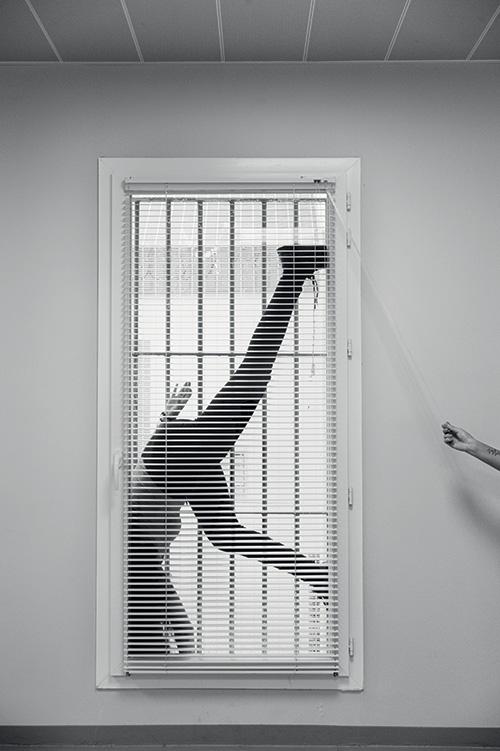

In the first part of Des prisons, the women inmates capture choreographic movements in black and white. The notion of suspension that these pictures convey encourages these young women to let go, to lift off from the ground that holds them down. Things bend, fall over and waver. The force that affects them accentuates the relationships between bodies, the distance between the artist and the inmates, between indoors and outdoors, between the free body and the body locked inside the penitentiary space. Something flows through – through words, through looks and then, in a continuity of sorts, through the movement of bodies.

Playing with faces, showing oneself without actually doing so, masking one’s identity, concealing one’s features, almost always. As if the mind were no longer relevant and only the body remained – a body that no longer feels nor controls, mindless, no longer a being but a doubly anonymous entity. In Valérie Horwitz’s work, the gaze is never penetrating nor direct: it resists. Or perhaps it hesitates.

The artist first set foot in a prison in 2017 on the occasion of workshops organised by the FRAC Sud for male inmates. She would go on to renew this experience for three more years, this time with women and girls incarcerated at Baumettes prison. Locked inside cages, like so many windows, the constraints they face are harsh. The vital force these conditions require, the graphic nature of the lines and the sense of an existence in parentheses generate boundaries that are impossible to define. These are supposedly invisible spaces that are presented to us through narrow openings. A minuscule place from which penance is to be perceived. While the poses are chosen by the inmates, the imprisonment ricochets upon itself in the resulting image.

But another space is created simultaneously through the words of the women: that of poetic writing. Their graphic layout enables us to cross over to the other side of the boundary. The publication of In Between (2022), which gathers together texts and black-and-white photographs, talks about this line that succeeds in regaining its ability to speak. Whether through an adjacent link or two distinct realities, the artist tells us that its aim is to “connect multiple singularities, in that there is not one reality but many perceptions of reality, fictional fluxes kept under the seal of an objected discourse wielded by power – fictions in friction with reality”.

However, movement is able to regenerate its impetuosity with Métamorphose [Metamorphosis] – an absolute necessity for forces to act, to alter reality. One is reminded of an image both tarnished and shifted, of the gestural turbulences of a Francis Bacon or an Antoine D’Agata, or the vertigos of a Robert Longo. Colour with a mirage at its centre, cenesthesia between them all, each playing their own rhythmic scenes. One could interpret these figures absorbed into the fabric as metaphors of shapelessness, as Rorschachs in the making, or as hesitantly-named insects. They may also be reminiscent of Loïe Fuller’s serpentine dancing, in an infinite variation of unsettling polychromy. Folds, unfoldings, decomposition then re-composition: the lines reveal, the colours highlight, smash formality to pieces in favour of a pure apparition. The result is weightless and solid, aesthetic and prodigiously free. The recent anthotypes Horwitz made using portraits of young women also suggest a broader intention, in which the work oscillates between vital revelation and a concealment imperative for its survival.

Another play on silence found its way into the project La Muette, initiated in 2017. The eponymous building, which was constructed in 1934 as a prison and internment camp, is the only one still inhabited to this day. Community spaces, high rises, places full of life but also of emptiness and constraints: this photographic portrait of one of the first French housing estates implicitly highlights that this Muette (Mute) intends to remain that way. Nothing comes out of this council estate: it is walled, on both sides. Because the archives give us nothing, all that we can do is juxtapose records of deserted locations and archive images. By combining various types of images in a loose presentation and overlaying these silences onto absences, the series seeks first and foremost to emphasise the additional marginalisation inflicted on these working classes as their voices are ignored. “Making do” has always been the artist’s initial prompt. Collaboration, which is the root of all of her projects, constitutes the gesture that causes forms to ricochet, as long as they continuously contribute to the creation of spaces of freedom.

Translation: Lucy Pons

45 photographs. Variable-size installation: single projection room, variable-size screen, armchair and noise-reducing headphones

© Valérie Horwitz

45 photographs.installation with variable dimensions: projection room for one person, screen of variable dimensions, an armchair and noise-reducing headphones

© Valérie Horwitz

Fine art print 133 x 200 cm on mat paper

© Valérie Horwitz

11 photographs - images from the series In Between, 2017-2019

© Valérie Horwitz

30 photograhies

© Valérie Horwitz