Simon Feydieu

August 23rd, on vacation in southwestern France, I received an e-mail with an offer to write about the work of Simon Feydieu, artist from Lyon. Attached was a photograph taken a few days prior, on the 18th, at Port de Meyran, just a few hundred meters away from where I was seated in my bathing suit. In the photo, strange, shapeless and archaic statues stood with their backs to the ocean. It was as if they’d been shown in my garden. I was frightened.

Struck by what I hoped was a coincidence, I ran to the port. I was looking to see if the sculptures were still there, or if it was a collage—a menace if true. In the picture, the forms seemed just to have left the studio, such that the light falling upon them seemed not to have come from the Arcachon sun but from neon lights in the enclosed space where the artist produced them. It reminded me of the startling shine of a full moon. There was something extraterrestrial about these forms left too long in the shadows. On site, I looked around, but found nothing but the stacked metal tables of oyster farmers. The artist had left without a trace.

Simon Feydieu takes his sculpture-creatures out of the studio to exhibit them: to see them in the light, in open air. He photographs them, then takes them down, sometimes the very same day. They’re often fragile, made of plaster or OSB, laser-printed and roughly varnished. They seem wobbly, compositions playing with instability, lack of substance and volume. Form is economical, but not the time spent building, moving and installing them. The artist seems less concerned with their longevity than the brief moment the works incarnate when they leave the studio.

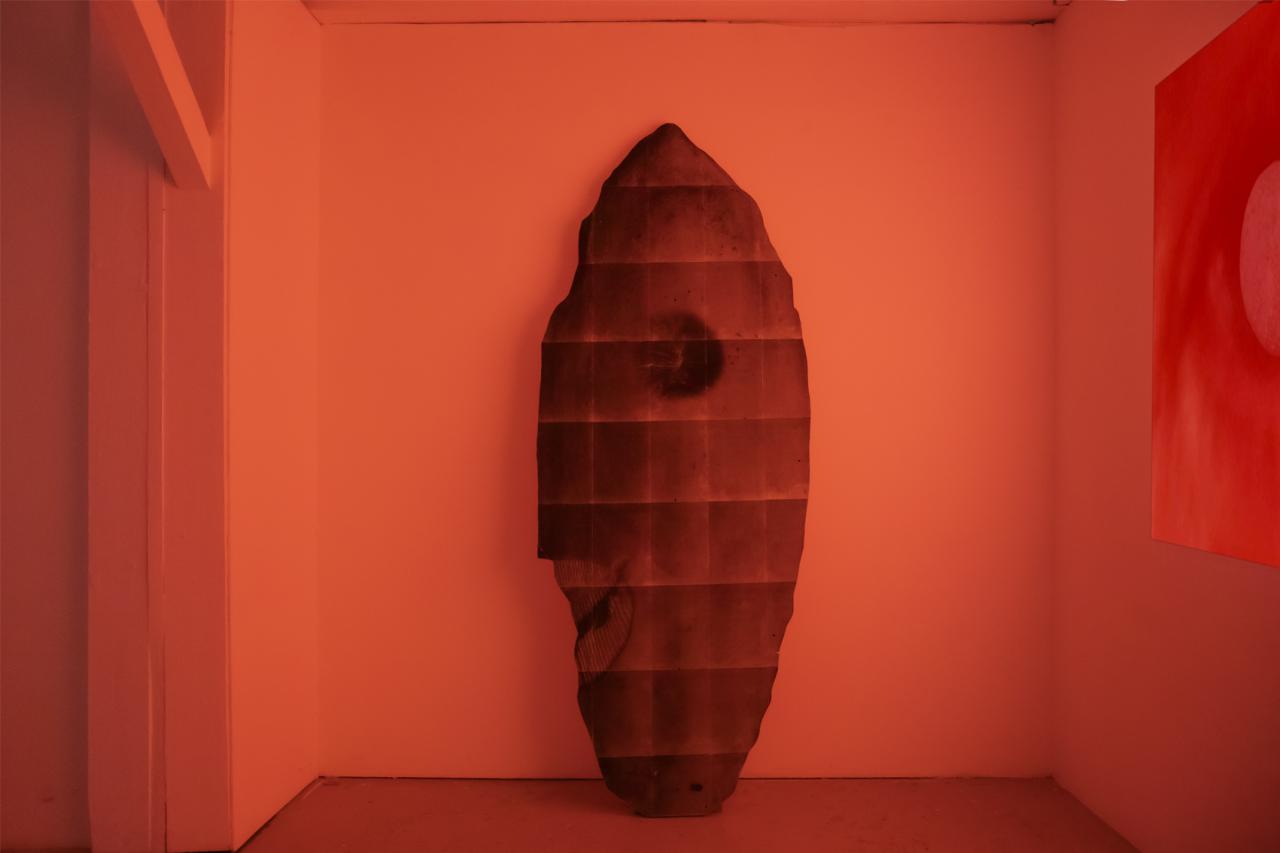

Five weeks after receiving the e-mail, not without apprehension, I left home at dawn for Pierre-Bénite, a small, industrial town near Lyon. I was late, but the artist had me wait outside. The sun shone brightly in the industrial zone, and as I finally entered, I was struck by the red-infused half-light of the interior. It was as if an inactinic lamp lit up the room. The artist’s pale face and clear eyes were indiscernible. I hadn’t met his gaze, and the rest was hard to make out. My eyes were not yet accustomed to the light, I had to open them wider.

The context made me cautious. In front of a video projection depicting an eye, three sculptures were lined up, the smallest at the front, the tallest at the back. The enormous eye winked softly and I didn’t know how to look at what I was seeing. Set upon trays with different bases, things like pistachio, peanut and walnut shells were piled up as on the coffee table of an obsessive teenager or a psychopath. Everything was red, not just from the light of the video projector flooding the installation—the objects were painted red, with oil and brush, in a confusing redundancy. I hadn’t yet seen these pieces, neither on his website nor in his portfolio. In fact, he’d just made them—for me, he said. That scared me too.

I moved around not knowing how to look or what to look at. Though I should’ve spoken, I couldn’t find the words. He wouldn’t stop talking, and the frenzy of his speech set me ill-at-ease. Then there was the red, not of blood, but of an open heart. The forms came from inner depths. Whenever I turned toward the video, the eye blinked in front of me at the pace of an intense scopic impulse, and I understood the directive: look again, attentively: it’s about vision.

Finally I saw the work, in full and in detail: on the trays, there were small wooden models of gas stations. Underneath them pedestals had been chosen to meet the needs of the occasion. He used what he found lying around–wooden crates, cardboard boxes and a radiator. In another context, it would be something else. It’s a versatile practice, nonchalant and pragmatic. From the vocabulary of manufacturing, he creates a work as archaic as it is unprecedented.

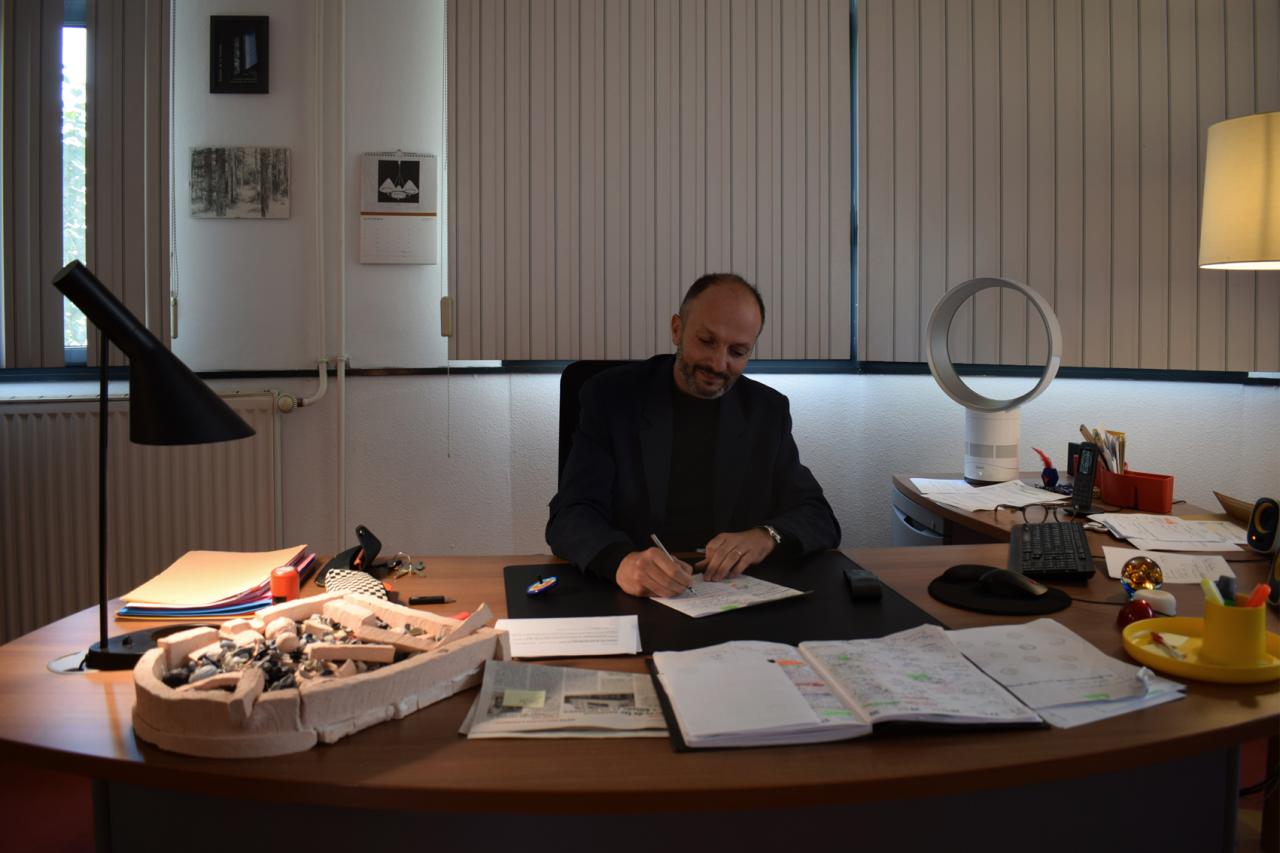

I discovered the chaos of his workspace. The artist maintains in his studio a big clutter out of which the oeuvre must emerge in order to be seen. The back turned to his mess, Simon Feydieu evoked the elegant sculptures of Barbara Hepworth, bronze and stone, and his interest in monuments, as I was witnessing Diogenes’ bedroom: plaster, laser prints, work in textile, unglazed bisque clay, scraps, shards, crust, a heap of forms and materials: an intimate mess.

The artist went on speaking. We agreed on similarities between his work and Fischli and Weiss, but who wouldn’t want to be associated with the Swiss team ? He went on to mention the artist-run-spaces he collaborated with, events organized at the studio, various art schools where he teaches, the time he spends tinkering, and recent developments – the following day, he’d go to the Drôme, the next to Marseille, returning to Truinas to photograph his sculptures under the full moon and meet the wolves at night.

Simon Feydieu is an insomniac. He’s maybe hyperactive, or ubiquitous. Certainly part of his artistic ontology involves making folds. Thanks to his studio practice, time is prolonged, doubled, recorded. It’s as if what happens there belongs to a dimension beyond the real. Many of the forms used in his work were captured or observed here, and the work consists in making it exist elsewhere. I should have brought up the video in which an American artist films his studio at night, as he might film his mind.

During one of the lockdown periods, Simon Feydieu was invited to create a mural for a middle school near his workshop. At this time, which was for most people one of withdrawal at home, he not only painted the mural, he also invaded the entire middle school, unleashing works in every room, from the cafeteria to the gymnasium, moving things around, appropriating a floor scrubber, installing targets, even setting up a giant bisque ash tray in the headmaster’s office. There’s surely a form of generosity in all this, but generally, his works emphasize the time that the artist, in his availability to the world, has shaved off of others who only manage to lament the hours passing by.

While he unrolled his Arches, sleeping bags onto which colored forms are sewn, he spoke of his adolescence, the skatepark, flexibility and gliding. He spoke of high school, and a time in which he’d defeated boredom, collecting at school all sorts of objects that lay around to make sculptures in classrooms and in the courtyard very early in the morning, before anyone had arrived, because he was already unable to sleep. Refolding the sleeping bags, he described some of his works with his voice from beyond the grave.

The story brought back a very precise memory from my teenage years: one Thursday, in my junior year of high school, a number of classmates and I were unable to find our belongings. The bell had rung five minutes earlier and we were still searching for them. When we were finally let out of class, a bright, clear light glared outside. There was a crowd in the courtyard in frightened chatter, I recall sneaking to its front: something had been set up in the middle of the football field. No one could quite make out what it was. We were watching like the Indians watched Portuguese schooners approach on the horizon. We circled round it, unable to figure it out. I thought of this again while reading experiences of “missing time” and accounts victims tell of extraterrestrial spaceships approaching them.

Journalists and policemen came to examine the object. Articles were published in local newspapers. The object was left in the courtyard for some long weeks before the school board dared take it down. Once dismantled, the sculpture became partly comprehensible: it included a longboard, a laser printer, chairs with gym mats lain between them, several motorcycle helmets had been hung on the ensemble like Christmas ornaments, backpacks, a blanket, a basketball, and at its peak was the metal water bottle I’d looked for everywhere, burst open, sparkling in the April sun. It was impossible to describe why the objects, assembled together, became unrecognizable. Then there were the elements that hadn’t been identified: students spoke of extraterrestrial origins, we simply had no idea where these things might have been created, no traces of the place nor the mind from which they’d emerged.

When Simon asked me to write this piece for him, he was addressing a novelist. He didn’t know we’d gone to see Elephant on the same day at Utopia cinema, or that in high school we’d both taken art classes with surrealist writer Jacques Abeille, author of Jardins Statuaires; neither of us had read his book, but I wonder if Simon sees in its title the presage of future works.

Translation by Elaine Krikorian, 2024

C-print, variable dimensions

HD video endlessly 1 min

Laser printing, plasterboard on frame, 250 x 100 x 5 cm

Ceramics, various objects, oil painting, textiles, models

Elephant, residency Cas Contact, Marcel Pagnol college, Pierre-Bénite, 2021

Elephant, residency Cas Contact, Marcel Pagnol college, Pierre-Bénite, 2021

Elephant, residency Cas Contact, Marcel Pagnol college, Pierre-Bénite, 2021

Permanent installation in the prinicipal's office

Elephant, residency Cas Contact, Marcel Pagnol college, Pierre-Bénite, 2021