Pascal Poulain

Pascal Poulain - Reciprocal Nature of Bodies: His, Ours

A society can be read more at its

margins than at its centre

(Eduardo Grendi)

When I discovered Cube, a recent diptych by Pascal Poulain, the implicit references to the ‘white cube’ reminded me of Brian O’Doherty’s essay “Notes on the gallery space”, which lies at the root of this term. Since it first made its appearance in 1976, it has been one of the most widely used notions in the art world, as we are reminded by Patricia Falguière in her preface to the French edition of the author’s writings.1 O’Doherty draws up a critique of the pseudo-innocence of the “white cube”, an expression he uses to describe the exhibition space in a gallery or museum, one which isolates works from the world in a sterilized, hermetic space, with an arrogant sterility about it. The presiding ideology is the one peculiar to the values of Clement Greenberg, the American theoretician and promoter of abstract painting in the 1950s in the United States. In addition to being absolutely not neutral, but rather filled with prerequisites, the gallery space is an idealized place whose function is to preserve the autonomy of artworks, render them sacred, and enable their sale.

In the following essay, I am going to try and follow this early critical summons in order to find my way into Pascal Poulain’s work and attempt to define what type of exhibition he is interested in, what exhibition styles he applies, and how the onlooker is, in his turn, exercised by what the artist sets up in his own shows. Knowing that, for him, the term “exhibition” is already, from the outset, laden with conflicting histories.

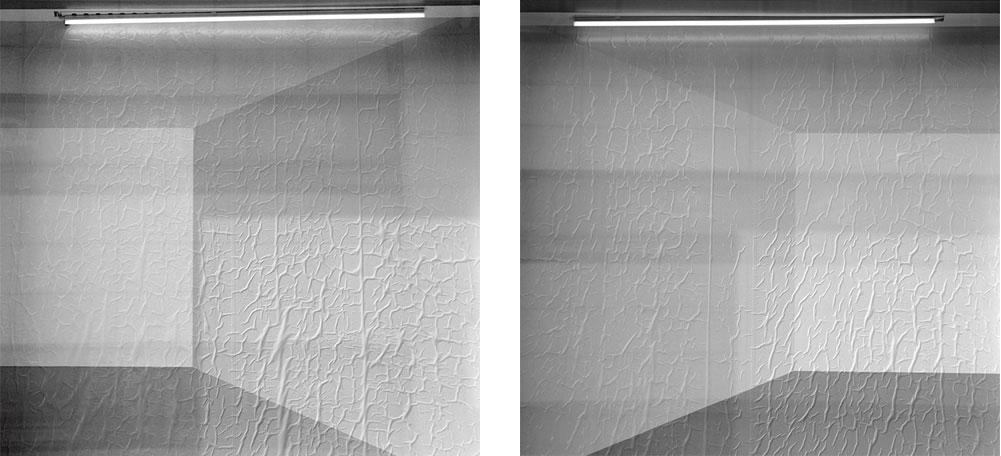

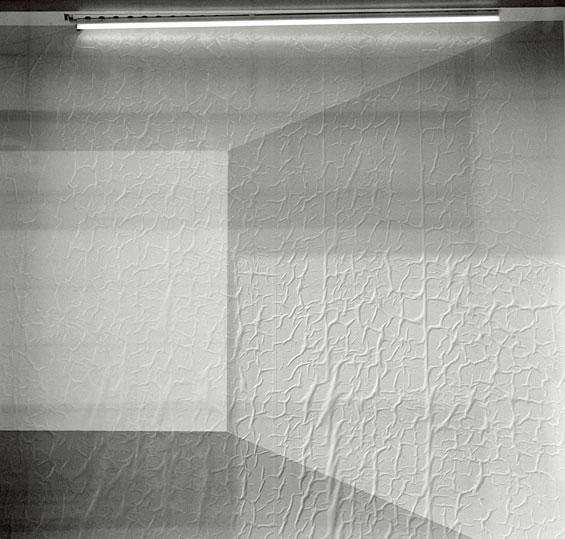

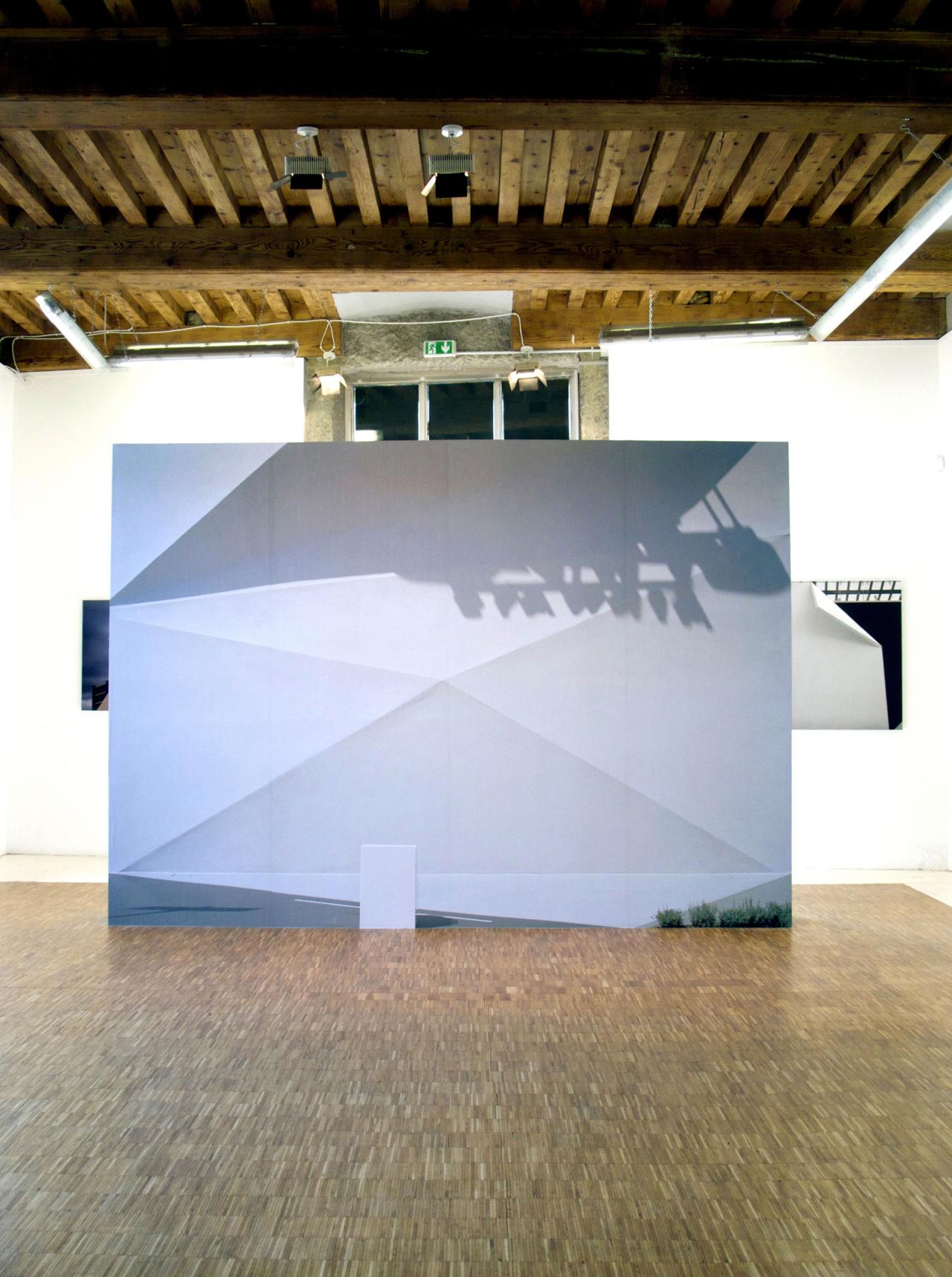

Cube, 2017

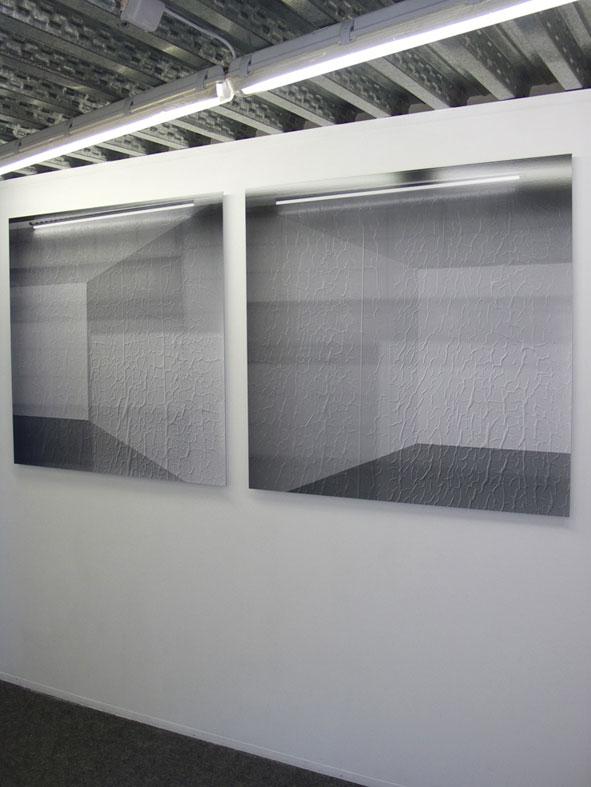

The representation of Pascal Poulain’s work in the Documents d’artistes website brings together what he calls “corpuses of photographs”. In the one titled “Geography Expert History Freak”, we find Cube, a diptych made in 2017 which shows two viewpoints of the interior of an empty room. It might be the photograph of an exhibition venue, but there is every reason to doubt as much: on the one hand, the graphic nature of this image stems more from drawing than from any representation of a space, and, on the other, the host of air bubbles informing the surface helps us to identify that what is involved is a wall on which has been stuck a poster depicting an empty space in three dimensions. This diptych calls for being deciphered in a more forthright way, because the two neons that we identify at the start as fixed to the ceiling are not part of the poster’s surface: no air bubble has formed above, they are in another space, detached from the wall, and they light up the warped poster. A slightly more probing decipherment still helps us to understand that there is probably a sheet of glass in front of the poster, because shadows animate the diptych’s surface, highlights coming from the space located behind the person who took the photo. There is a photograph of Cube installed in an exhibition venue—Pascal Poulain regularly takes this type of exhibition view to show the spatial arrangement of his images. And it just so happens that the diptych is to be found in front of two neons in an exhibition space. The onlooker is thus in an almost symmetrical position to that of the photographer when he pressed the shutter button.

One of the keys for understanding Pascal Poulain’s work has just been stated. Because if we generalize from the experience of reading Cube, it is tempting to put forward the idea that this work brings to our eye a way of thinking about our relation to the differing registers of exhibition, and it is even tempting to see therein a way of thinking about the seduction strategies that society, as a whole, is applying today. This is a work which, in return, questions the spectator about his own way of looking at images, through the way in which the artist exhibits his work and spatially arranges the photographs.

But it is not a work which concerns the art exhibition space, in the strict sense of the term, which O’Doherty was analyzing. Furthermore, Cube was not made in a gallery or a museum, it is a hoarding found in a city, where the artist photographed two details, leaving the advertising message off-screen, as it were. The exhibition venues he is interested in are not enclosed, they are those outdoor venues where the prêt-à-penser or ‘ready-to-think’ is presented: urban or rural spaces, promotional premises and showrooms in scale with the landscape, the public place, contemporary architecture, and so on, where, today, many different exhibition and seduction strategies are to be found, with much sound and fury. So why bring in Brian O’Doherty’s analysis? Because, in 25 years, everything has conspired to make everything that is in the sights of “Inside the White Cube” now “outside”. The neutral surface, the forms of discourse and the prerequisites, the ubiquitous design strategy and commercialization. The model which Clement Greenberg et al managed to impose on the whole world, to do with the inside of the gallery and museum, has been successfully imposed by Frank Gehry—from the Bilbao Guggenheim to Vuitton, Paris—first and foremost on the envelope of contemporary museums, subsequently contaminating the city and society in its entirety.

Looking at Images

These strategies have in fact spread to the point of being present here, there and everywhere today. When Giorgio Agamben describes, after Foucault, what an “arrangement” is, he is talking about its egregiously negative and oppressive character: “those heterogeneous and dominating assemblages, spatial apparatus, discourses, institutions, practices, tools, laws, etc., whose aim is to manage, govern, control and guide—in a would-be useful sense—the behaviours, gestures and thoughts of men”.2 He speaks out against the system of constraint and subordination to external and fictitious identities and subjectivities.

Theme parks, showrooms and world fairs clearly correspond to this definition; as far as the city and contemporary architecture are concerned, things are a little less obvious, but as Patrick Marcolini writes about psychogeography among the Situationists:

“Instead of inventing its specific ends, and conveying its own content, movement in the city, insomuch as it is subject to technical and economic rationalization, sees its set objective as a precise destination corresponding with the activity to be carried on therein. […] Insomuch as the city is subject to capitalist coding, it is thus merely an abstract surface on which there are permanent flows in motion, whether these flows are made up of goods or human beings. […] Corresponding to the abstraction of this quantified space on which glide flows of objects, all of whose qualities are subsumed in the category of utility, we find the abstract rationalization of ways of thinking which have been developed in liaison with the boom of capitalism and industry”3. […]

It suffices to look at Pascal Poulain’s photographs to be duly persuaded.

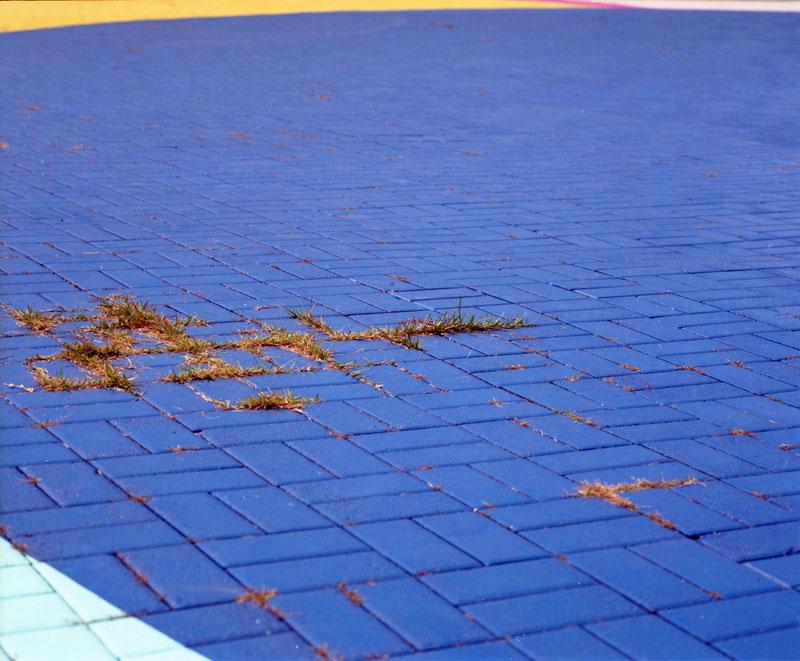

The artist does in effect seek out confrontation, he faces up to things, he tries to stand his ground. He painstakingly chooses different types of places in which he will take photographs. The Situationists used the term “spectacle”; Pascal Poulain uses the term “image”: a showroom for sign boards, or for cemetery furniture, where the arrangements of spaces and objects in no way tally with their primary function, but with a clear commercial purpose: an international exhibition or universal exposition (Milan and Shanghai), or an international garden show (Hamburg and Copenhagen), where national pavilions blossom, like so many discourses turned into spaces; a theme park like the Puy du Fou, in France, Santosa, or Tokyo Disney Sea Resort, where the trap is organized in such a way that the public is unable to resist, and is “caught”. And clearly Shanghai, Dubai, Singapore, Tokyo, Bangkok, New York, Rotterdam, Almere, Seoul, Osaka, Berlin: where image-architecture is displayed and turns into a shop-window and an argument in the competitive struggle engaged in by cities all over the globe: “I look at what creates imagery and I take photographs. In my work, there are never any images in the broad sense, but photographs which are interposed with imposed images”.4

Pascal Poulain goes to the edge. He is wary of everything that is photographic and exotic, he photographs anomalies through the well-oiled cogs of the arrangement which he is trying to confront. He is interested in what might seem to be anecdotal, and he might well adopt as his own the words of Carlo Ginzburg: “I tend to analyze anomalies because I think that, from the cognitive viewpoint, anomalies are richer than norms. Because the norm cannot include all the transgressions made with regard to it, whereas anomalies inevitably include, by definition, the norm”.5

Keeping this idea of “Ginzburgian” anomaly in mind makes it possible to look at Pascal Poulain’s photographs (spread over 20 years of artistic activity) and then single out what he introduces to withstand the above-mentioned apparatus.

His, Ours

Pascal Poulain, whose photographs are very sophisticated in terms of framing, has an undeniable power of visual persuasion. It is worth noting that the performative factor of the shot is special for him (the framing sought calls for finding the position which imposes a certain number of movements, back-and-forths, heightening or lowering the viewpoint). The artist’s strategies in the face of ubiquitous images concern and are incorporated in his body: moving, setting off in quest of what might be intercalated between the lens and the subject, or making a sidestep, waiting for the public to leave, for the theatre to empty out, gain height, etc. They may also have to do with compatible weather conditions, when they will blur the contrasts, introducing a mist or a ray of sunshine.

As we have seen with the two neons in Cube which place the onlooker and the photographer in symmetrical positions, the gallery, the museum and the exhibition venue are all places where the spectator’s experience will be activated, and thus places where it will be able to touch, in acts, a critical line of thought. Pascal Poulain is constantly thinking “exhibition”. During his preliminary research, when he chooses the places he will go to, and on the Internet, observing cities grow and develop thanks to webcams “exposing” construction sites all over the world. At the moment of the shot. Returning from his journeys and uploading his photographs onto his site pascalpoulain.com, which he likens to his laboratory. And by creating the corpuses regularly delivered to Documents d’artistes: “I am forever re-visiting the chronology of my work, in a way I am taking another look at it so as to correct my output, by association, by deployment, by displacement […]. From 2010 onwards there is in my work a kind of reconciliation between the praxis of photography and that of the arrangements devised for the show”.6 What remains for the artist at a time when everything is becoming imagery and when photographs are being taken everywhere and by everyone? In this heady situation, Pascal Poulain thinks that what remains for the artist is the praxis of space. Because what is involved is rendering malleable, transformable and “re-architecturable” the organized space of things and thus of the ubiquitous image-apparatus. By not submitting, by making a sidestep, he adopts an attitude which packages his photographs to be shown in “re-organized” spaces, too. To be able to see his photographs, bodies will have to be set in motion. The experience of his photographs is rooted in a reciprocal performativeness of bodies: his own, and ours.

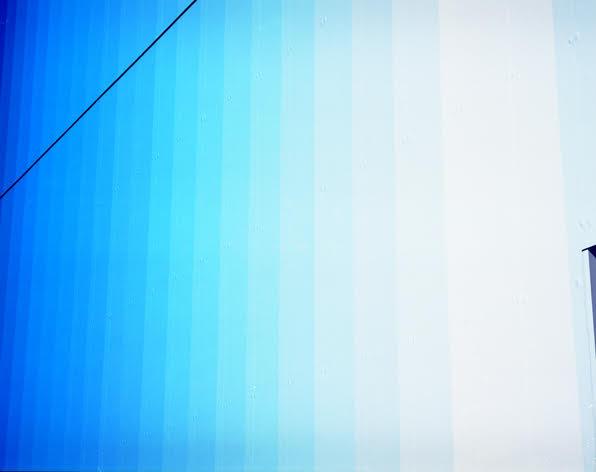

The exhibitions held in the early 2000s, using images drawn by advertising people, are the precocious witnesses of this type of investigation: Pascal Poulain made those images monumental, they took shape by becoming bas-reliefs, curled up in gallery spaces or ending up in inappropriate spaces. The removal from their original environment and the switch in scale lent them a doubly critical look. This tendency towards the performativeness of his spatial arrangements is today confirmed in the exhibition modalities like the one for Cube, which we looked at at the beginning of this essay, or Expanded Color, where the shot pre-incorporates the exhibition space and presents a critical coloured surface; in the end, this latter literally encompasses the visitor and delightfully calls to mind Color Field paintings.

And it is probably no coincidence if Pascal Poulain is making reference here, as it happens, to the type of formalist painting being aimed at in Brian O’Doherty’s critique of the ‘white cube’.

Translated by Simon Pleasance & Fronza Woods

Notes :

1. Falguiere Patricia, “A plus d’un titre », in O’DOHERTY Brian, White Cube. L’espace de la galerie et son idéologie, JRP | Ringier, pp. 5-32.

2. Agamben Giorgio, Qu’est-ce qu’un dispositif ?, Rivages poche, Oaris, 2014, p. 28.

3. Marcolini Patrick, Le mouvement situationniste—une histoire intellectuelle, L’échappée, Montreuil, 2013, p. 92.

4. Poulain Pascal, ‘e-mail interview’, 18-27 November 2019 (unpublished).

5. Ginzburg Carlo: Les Matins aux rendez-vous de Blois : sur les traces de l’historien Carlo Ginzburg, France Culture, 11 October 2019.

6. Poulain Pascal, “interview #2”, 4 November 2019 (unpublished).

2 photographs, Lambda-print mounted on Dibond, 100 x 101 cm

Diptych detail, photograph on the left

Diptych detail, photograph on the right

View of the exhibition “La cité d’images”, Le Bleu du Ciel, Lyon

2 photographs, Lambda-print mounted on Dibond, 90 x 130 cm

Collection Institut d'art contemporain, Villeurbanne/Rhône-Alpes

12 photographs, Lambda-print mounted on Dibond, 60 x 72,6 cm

2 photographs, Lambda-print mounted on Dibond, 110 x 137 cm

2 photographs, Lambda-print mounted on Dibond, 80 x 96 cm

Lambda-print mounted on Dibond, 120 x 151 cm

4 photographs, Lambda-print mounted on Dibond, 106 x 130 cm

Lambda-print mounted on Dibond, 100 x 131

Photograph, Lambda-print between two sheets of Altuglass, 80 x 180 cm

Lambda-print mounted on Dibond, 110 x 120 cm

Lambda-print mounted on Dibond, 130 x 90 cm

echoing the Biennale de Lyon, INSA Lyon, 2015

Lambda-print mounted on Dibond, 100 x 131 cm, Collection INSA Lyon

blue back collage, format variable

View of the exhibition Guillaume Janot, Pascal Poulain, Le bleu du ciel, Lyon, 2016

Forex cut out, 1 x 2 m each

View of the exhibition « De l'interprétation », Zoogalerie, Nantes, 2009

Adhesive images, 24 m2

View of the exhibition “We're gone”, La Salle de bains, Lyon, 2001

Digital print on micro-perforated Vinyl

4 x 18 m, Production Art3, Valence, 2000

View of the exhibition « Parenthèse (voyage n°2 »), Lycée François Mauriac, Andrézieux-Bouthéon, 2002

« Réseau Galerie » arrangement of the Institut d'art contemporain, Villeurbanne/Rhône-Alpes

9 photographs, blue back collage, 106 x 130 cm

9 photographs, blue back collage, 106 x 130 cm

Le bleu du ciel, Lyon, 2016