Olivier Nottellet

An absence so profound it tarnishes mirrors

In the walls, keeping things alive. I cannot say that O.N.’s murals are passages. Rather, they are hallucinations, the fruit of distresses old and new. They are a matter of survival and of keeping things alive. As Mahmoud Darwish says: how can my tomorrow be saved?

John Berger says: the number of lives that enter any one life is incalculable.

Therein lies the emotion, held and rendered. Time goes by. There is something disappointing (and funny) about saying it that way. O.N. has another way of putting it: empty office chairs, green or white sheets of paper, yellow masses, black lines, the breeze of emptiness out of range (from the back of my eyes). I will not leave the island of memories with you — that’s a song. The island is 1998, the die [Le Dé], flowing by. 2015, by very little [à peu de choses près], I get involved: you’d be there. 2013, tender [tendre], a map of time past.

Your back is a bridge I can cross.

I found out that a young man had died for love. The intense shock I experienced came from the fact that this love was somewhat invisible, that it was very silent, and that they both almost always walked alone. What shocked me was that one of them carried within him this power of death, of giving death, of causing it in spite of himself.

Hypothesis for a narrative,

In 2015, O.N. sat down beside me and offered to help me. I agreed. It started out with a notebook I had to fill up. I numbered it 1. I drew a house in it, made out of 5 lines that didn’t quite meet in its left angle. Under this drawing, I wrote: new house. In this summer of 2023, I phoned O.N. and made notes in notebook 23 while I sat on an office chair in a six-line house.

A liminal space shared in silence.

I hear where O.N. wants me to look.

He tells me things about his life, I remain close to the edge, I find myself stuck on the threshold, which is the exact space in which all of O.N.’s forms take shape. He talks to me, but he doesn’t talk to me. His work doesn’t observe (and by this, I mean that from a phenomenological perspective, a point of view isn’t an address), but rather exposes — stuck inside, we live in there and all the peeping Toms can look at us at leisure through their little holes.

Imagine a house when you’re not in it; it’s not so much the subject but the emotion that it stirs up. Yesterday evening in the car (the outlines are blurred.), a windscreen, music, cinema, that kind of cinema, which one could qualify as a nostalgia of fantasy. Actually, one has never had that desire, but the sadness of that desire disappearing settles in. In fact, like the insects dead by the hundreds on windscreens, the memory of the thick layer and of the kind of future that it implied and is now long gone.

Go easy on me, we kiss, I fall.

John Berger says: in art, the body is printed on paper as a sign of its endurance. O.N.’s silhouettes tell of this endurance; they come back from their successive disappearances, they move from wall to wall to paper, year after year.

In fact, O.N. tells me: that forms appear, persist and are made visible through a gesture which belongs to a certain category that only exists for romantics. A sort of necessity, the reference frame of which is always fairly questionable. I curl up in it.

O.N. says that the form wanders around and that it’s up to us to accept it or refuse it. That’s also my belief. Marguerite Duras says: for a long time, I thought that these were exterior voices, but now I don’t think so, I think it’s me if I didn’t write, me if I understood better, me if I loved women, you see, if I loved a woman, me if I were dead. That’s also my belief.

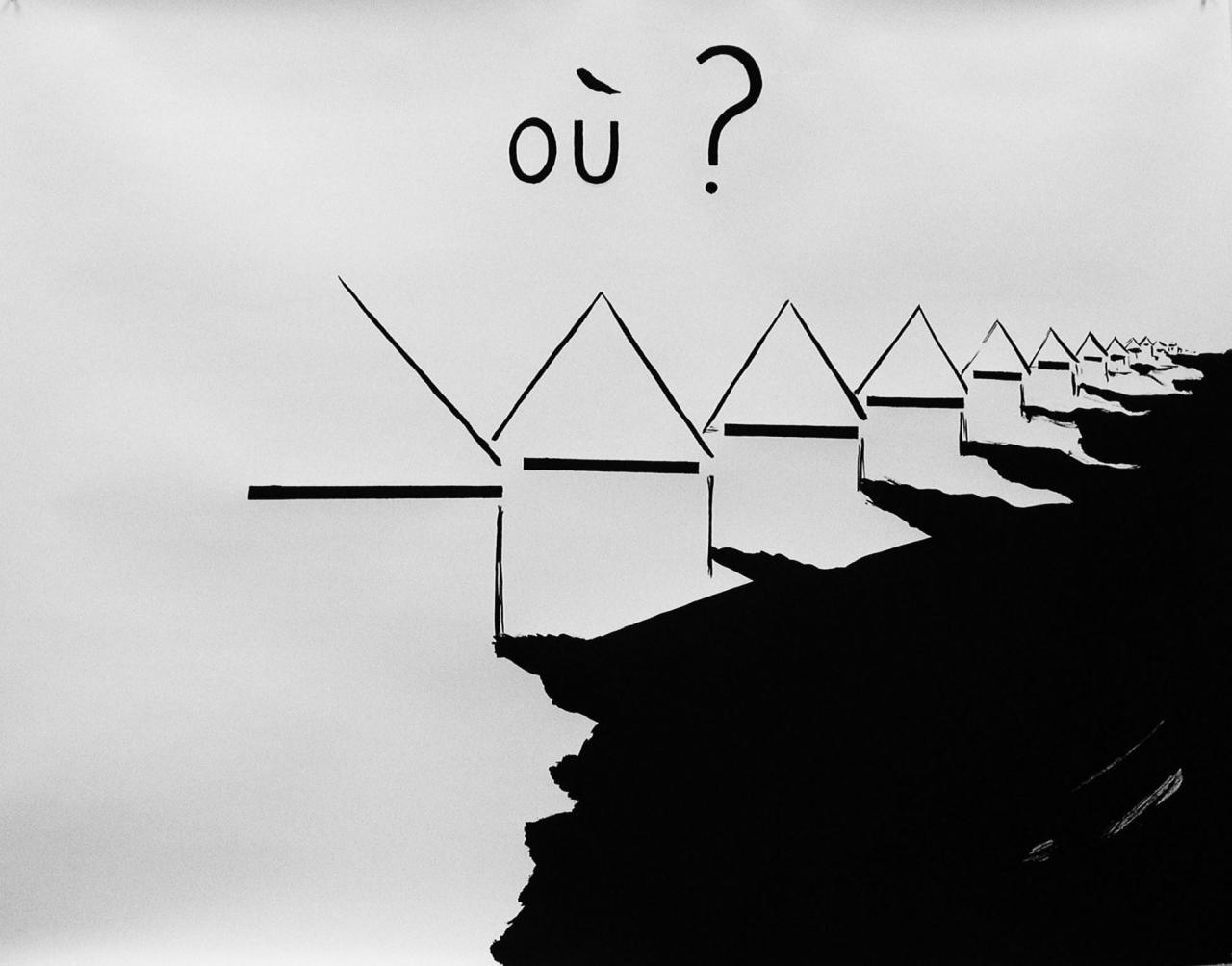

A white surface in a row of houses, or rather three times four lines that could be houses or the view from the beach in Le Havre, those little huts above which is written: WHERE [OÙ], to which I answer: in the car, I wanted to qualify the emotion, the setting sun, I thought about waiting rooms, which ones — the one in the hospital, at the job centre, at the benefits office. Perhaps there are some tasty moments after all.

I remember the time when I hadn’t at all processed that everything dies, I remember being there in a green waiting room, a TV was broadcasting that day’s horoscope on loop, and I was deeply in love with life, frozen before tragedy: between the accident and slow agony, there is survival. A few leaves [Quelques feuilles] 2014, a double-backed office chair, each of its legs fitted with a small mirror. A stimulus in the perspective of vision: wonderment, love, desire, hope; that is, the threshold of death and devastation; that is, the threshold of a kiss.

O.N. says: office chairs look like they have spines. Could it be that office chairs are ontologically related to desire? O.N.’s entire body of work is a circulation through the liminal spaces in our lives; maybe it connects them and we look at each other from one end of a hole to another — I am at the bottom of that hole and I love you. Space trickles like sand, slips through our fingers, or something like that.

O.N. tells me about himself, he talks about love and wage earning. He talks about AIDS, about partying. I am caught in an expanse, and this expanse is the result of passage and transition, wherein relationships are managed and social statuses are defined. O.N. describes the figures that populate his drawings, whether waiters or traders, same clothes, same people.

This is what they tell me:

they undressed for me.

Everyone wanted to have sex with me. They didn’t.

I don’t think they experienced desire. I wonder, in that moment, which one of us felt any kind of palpable desire. We slept together, I woke them up, I fed them. They wanted us to stay together for life. And I loved them — well, I loved two things. That they seemed to need me to execute elementary daily gestures and the forms these gestures produced; them, lodged in an office chair that starts to roll away and falls into the space between what they can see and what I see. That they loved me that much (gave me a home), that they needed me that much, sprung up again in the form of a certainty (a house).

I was tethered to their love, to their needs. We were together. Members of a unit that wouldn’t have survived without the others. What is over is unity. Maybe it left them wide open or better, curled up in that opening: a consequence of prior inflammations.

Art history is complex, sinuous and sad — that’s what O.N. tells me and I don’t even think of art history most of the time. This time I think about it and answer: why? Because it is a cemetery of forgotten people.

And yes,

Silhouette, synonym, figure: they are forgotten somewhere between a quarterly benefits return and their inclusion in art history by way of a small exhibition at the local library. Well,

between you and me,

I had made a list

Of everything I was supposed to say

A list of sentences pronounced,

A list of sentences that I had dreamed of but would never write

I pushed open the door to the benefits office, to the job centre, to the library.

I don’t even push the door open because,

I love flour felt [farine-feutrine]

And that it’s just a shop window covered in felt except in one place, a sort of rip that is in fact quite outlined, quite artificial;

Through it one sees a floodlit heap of flour dotted with coins.

There’s about ten euros there, probably less.

There’s a hand, too,

And I take it.

How far away does one need to be before one starts to become absent?

Translation by Lucy Pons, 2024

— Introduction by Olivier Nottellet

When I was told that the Fondation de l’Olivier was giving me the opportunity to contact an author to write a text about my work, my immediate thought was that I didn’t want a traditional critical text. Rather, I wanted to share a different approach, a new interpretation of my work, akin to new literary forms that are not afraid to combine genres (criticism, novel, biography, journalism…). I wanted to go off the beaten track that I’d treaded before, to step away from an analysis, which, while I don’t disown it, I now want to replace with an approach that carries more uncertainty than meaning. Eugénie Zély, whom I almost immediately chose, was an engaging and enthusiastic student before she became a friend. I reckoned she would be able to see through the mass of my visual output, see the outlines of reality, see where tangible presences appear between the lines of my preoccupations. No cornerstone here, nothing sensational, a few snippets and clues here and there, brought to the surface of my career to highlight their singularity, which is closely linked to the contour of periods spanned. Perhaps it is serendipitous history more than it is art history.

Photo : © François Deladerrière

Photo : © Marc Domage

Exhibition view Tendre, CRAC Languedoc-Roussillon, Sète

Photo : © Marc Domage

Ink on paper, 90 x 110 cm

Private collection

Office chairs, strap, mirrors

In situ intervention in the window of the Frac Île-de-France / Le Plateau

Flour, felt, coins, lamp

Photo : © Martin Argyroglo

In situ intervention in the window of the Frac Île-de-France / Le Plateau

Flour, felt, coins, lamp

Photo : © Martin Argyroglo

ink on paper, 24 x 32 cm

Ink on paper, 24 x 32 cm

Ink on paper, 24 x 32 cm