Maire-Claire Mitout

Marie-Claire Mitout: The Side Streets of Painting

This is a book that, like the artist’s work, goes back in time. Marie-Claire Mitout is a painter, but one who always walks the “side streets of painting.”.1 The series Les Plus Belles Heures (The finest hours), begun some thirty years ago, is a way of stepping through time, like the artist steps through art, using a Chinese abacus. She sets herself the task of painting to unravel the knots of the world, to celebrate life and reimagine it, taking inspiration from stories, moments, simple events, a phrase overheard, the taste of an apple, or a run-in with a cat. At the start, in 1990, the artist produced three hundred paintings, always from memory. She set a goal of producing one painting per day over a year, every five years. After the second series, she decided to produce the same number of paintings but over a five-year period. The paintings are organized in families, with more or less members, around themes including Greek tragedy, an imagined Japan, magical shirts, or simply landscapes…

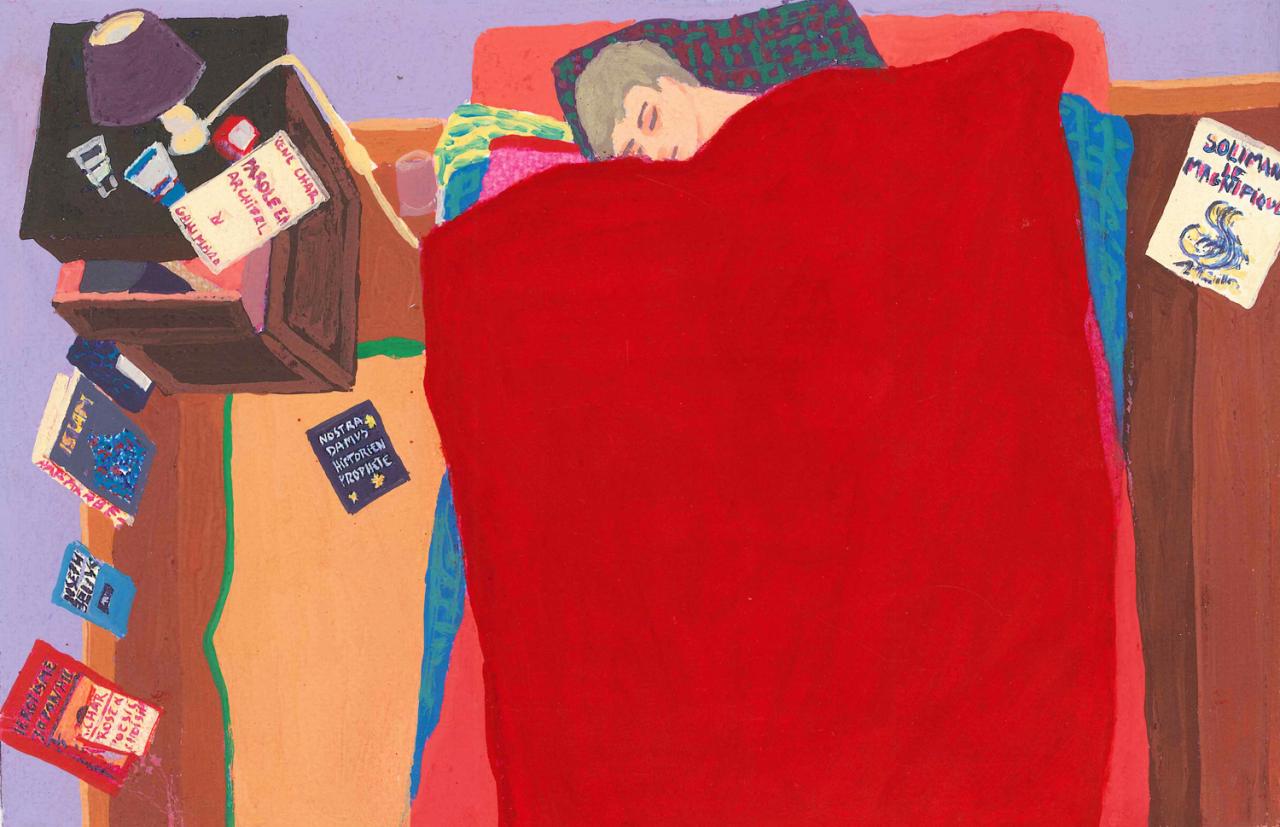

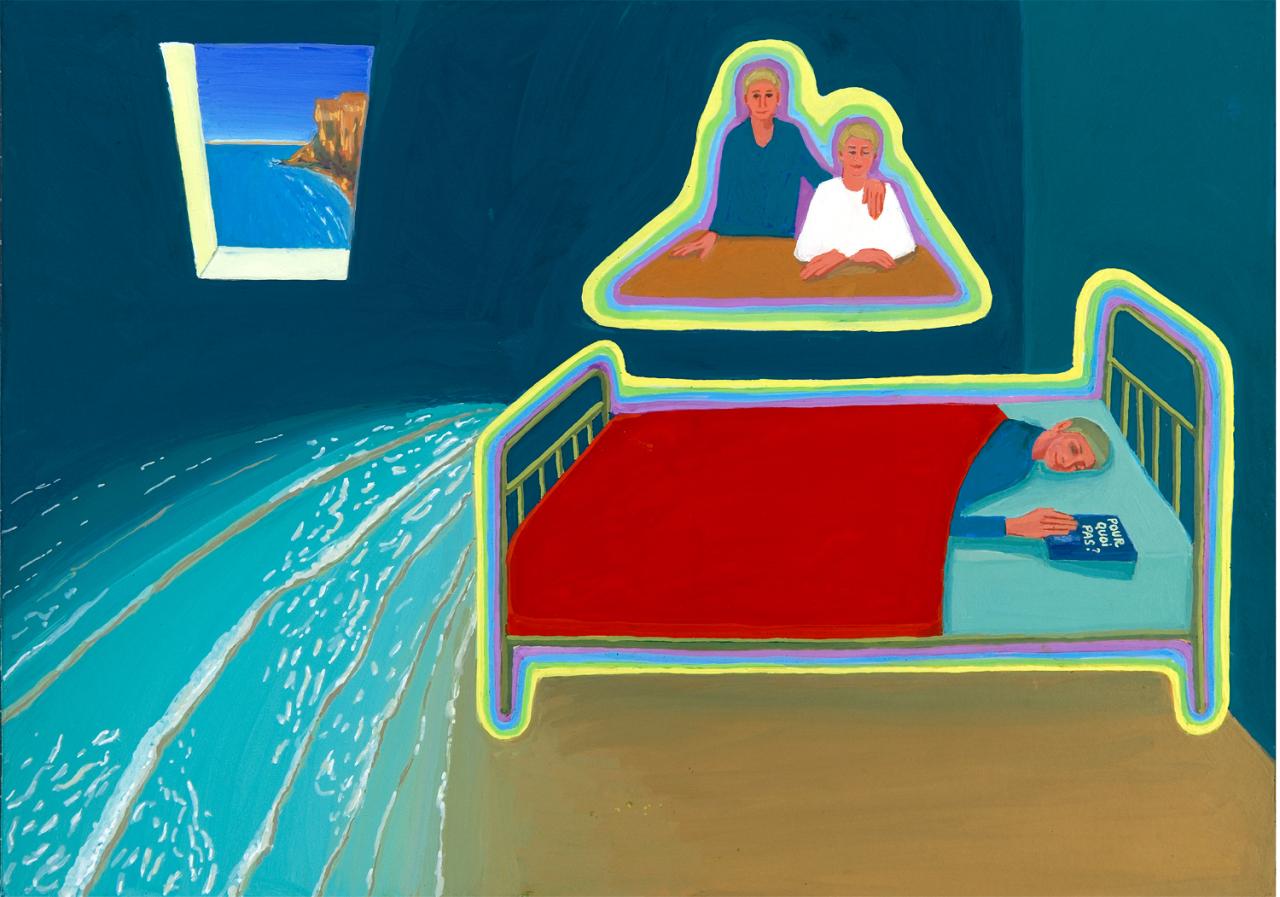

She always begins with words, written in a notebook every day: first, the weather, then what she’s seen, then a detail from an illuminated manuscript, a visit with a friend or relative, or a scene from the library. Before each painting, words are transformed into illustrations, which remain as private as her writing. The series Les Plus Belles Heures is composed of A4 gouaches, and several large oil paintings. In general, everything is expressed already in the first image: a figure lying on a bed with a red blanket, surrounded by books, a space of dreaming and withdrawal (September 3, 1990; gouache; captioned: Autobiographical series “Les Plus Belles Heures,” Trace of the finest moment of the day before).

Marie-Claire Mitout grew up in Limousin, where she recently returned to paint. After the École des Arts Décoratifs in Limoges, she attended the Beaux-Arts, first in Lyon and then in Paris, studying in the studio of Christian Boltanski, who had just begun teaching. But life in Paris was hectic; she returned to Lyon, where she now teaches at the architecture school, setting up a studio in the woods, somewhat removed from the city.

From Robert Filliou she learned the “principle of equivalence: well done, poorly done, not done,” according to which art is a subject matter open to all. Her work is an invitation to see the world differently, where images from art history stand beside those from daily life. There is an element of the ex-voto about her work, as if there were something to figure out, like paintings by a clairvoyant.

Searching through her gouaches, we can discover several states of consciousness. Marcel Proust kept her company for a long time. In her words: building a narrative allows you to go back and forth between the world’s losses and gains, and art is a way of learning to love it. She speaks of her work as a perpetual beginning-again, as she addresses the succession of days and the finest hours that make them up. Until very recently, she hadn’t sought to sell her work. An offer to produce a book with Roven éditions led her to finally select some for sale. Passing through publishing was, in fact, the suggestion of her “Good Council,” who appears from time to time in her work, at her side.

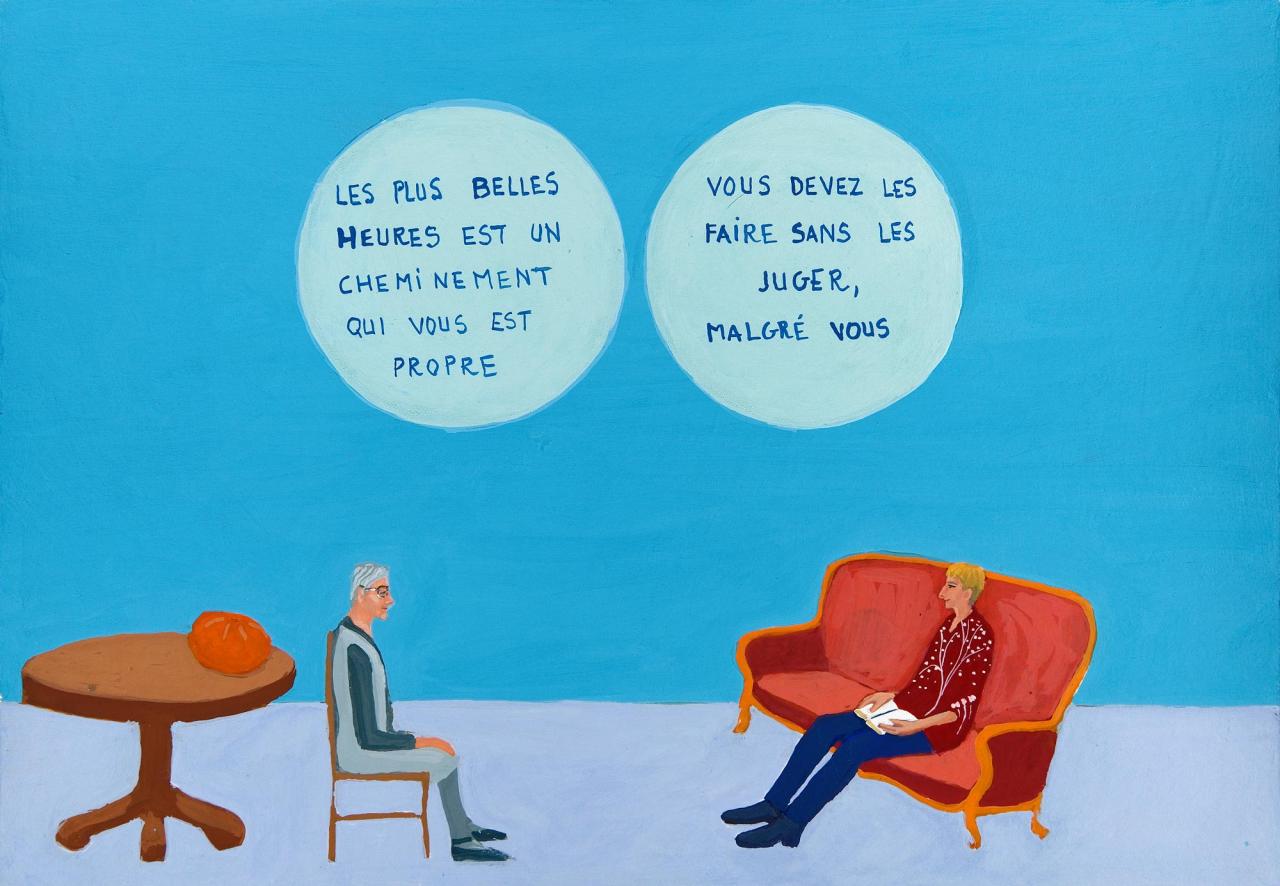

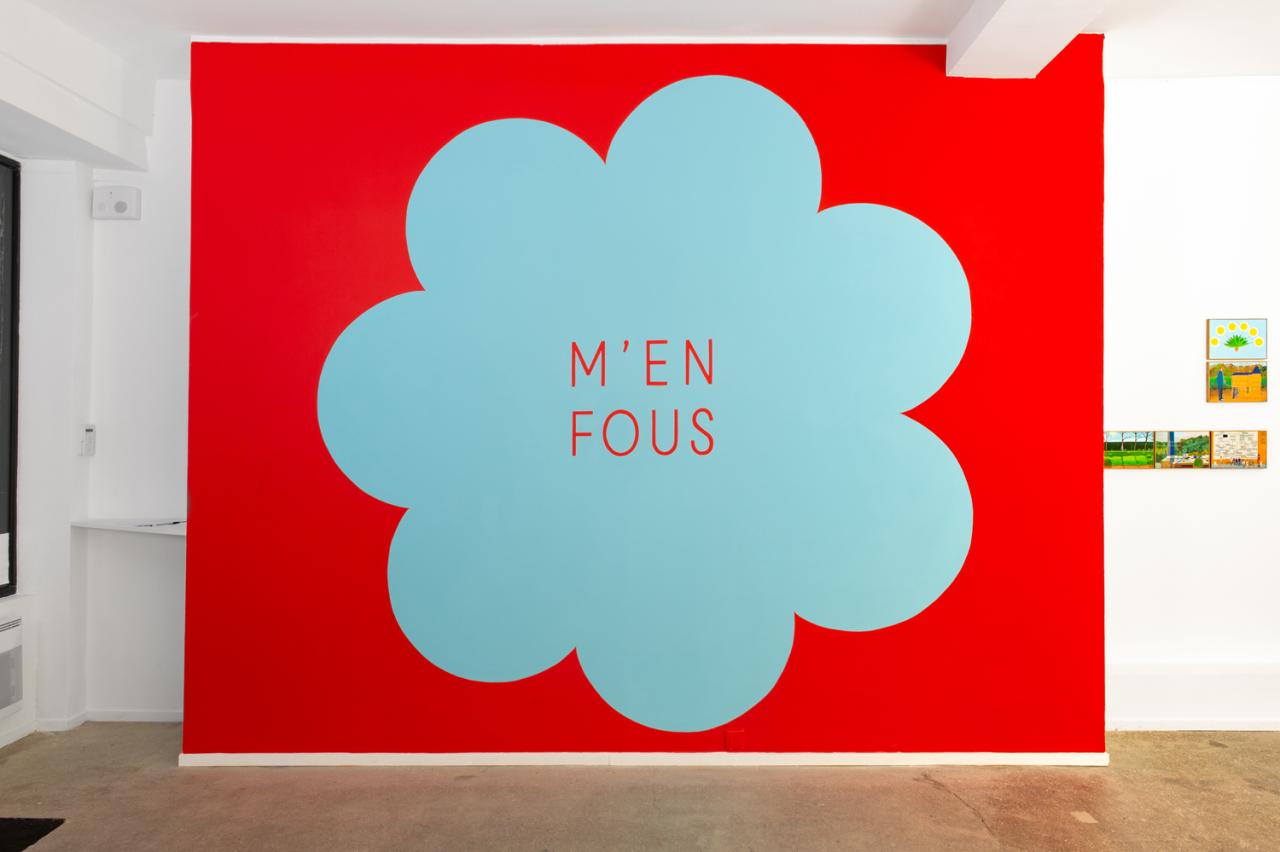

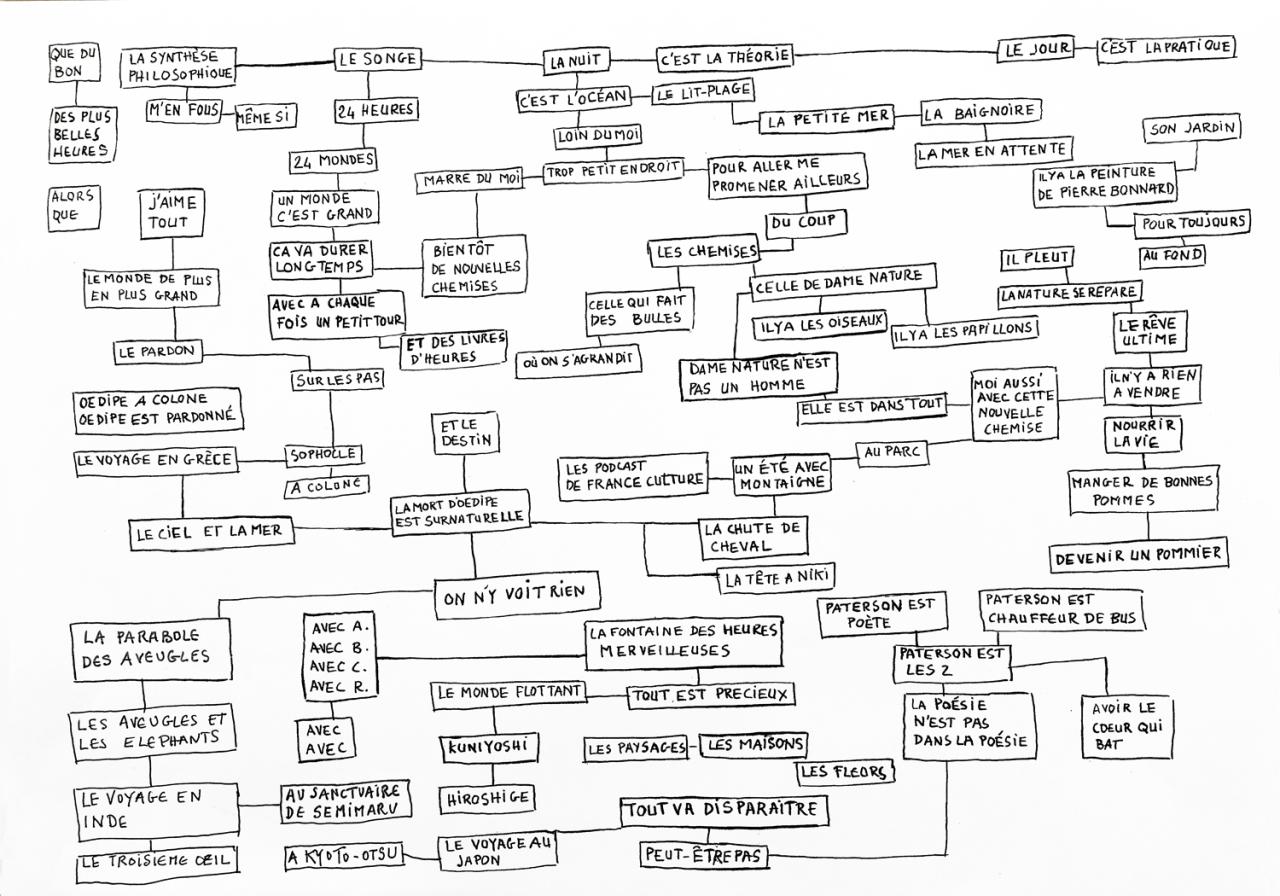

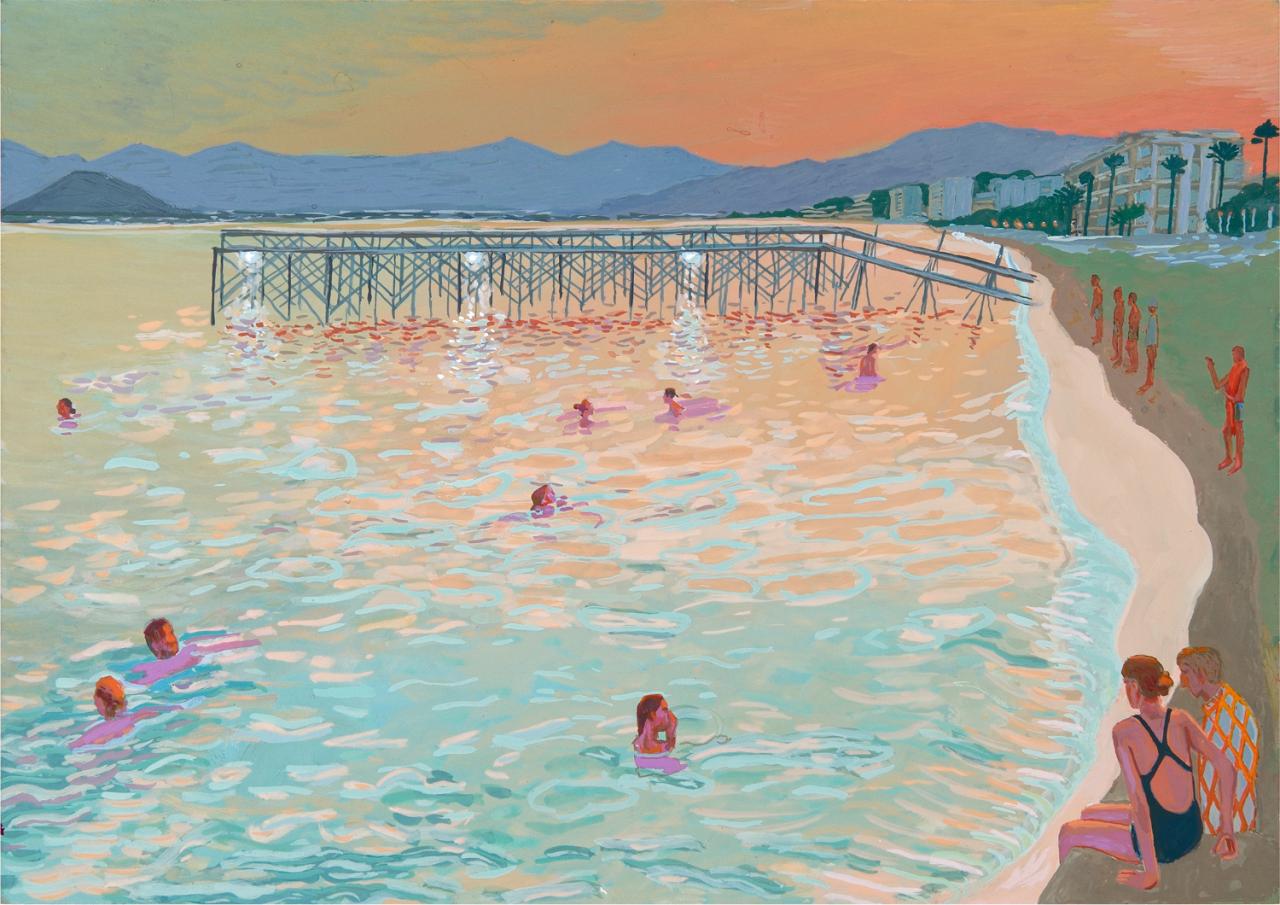

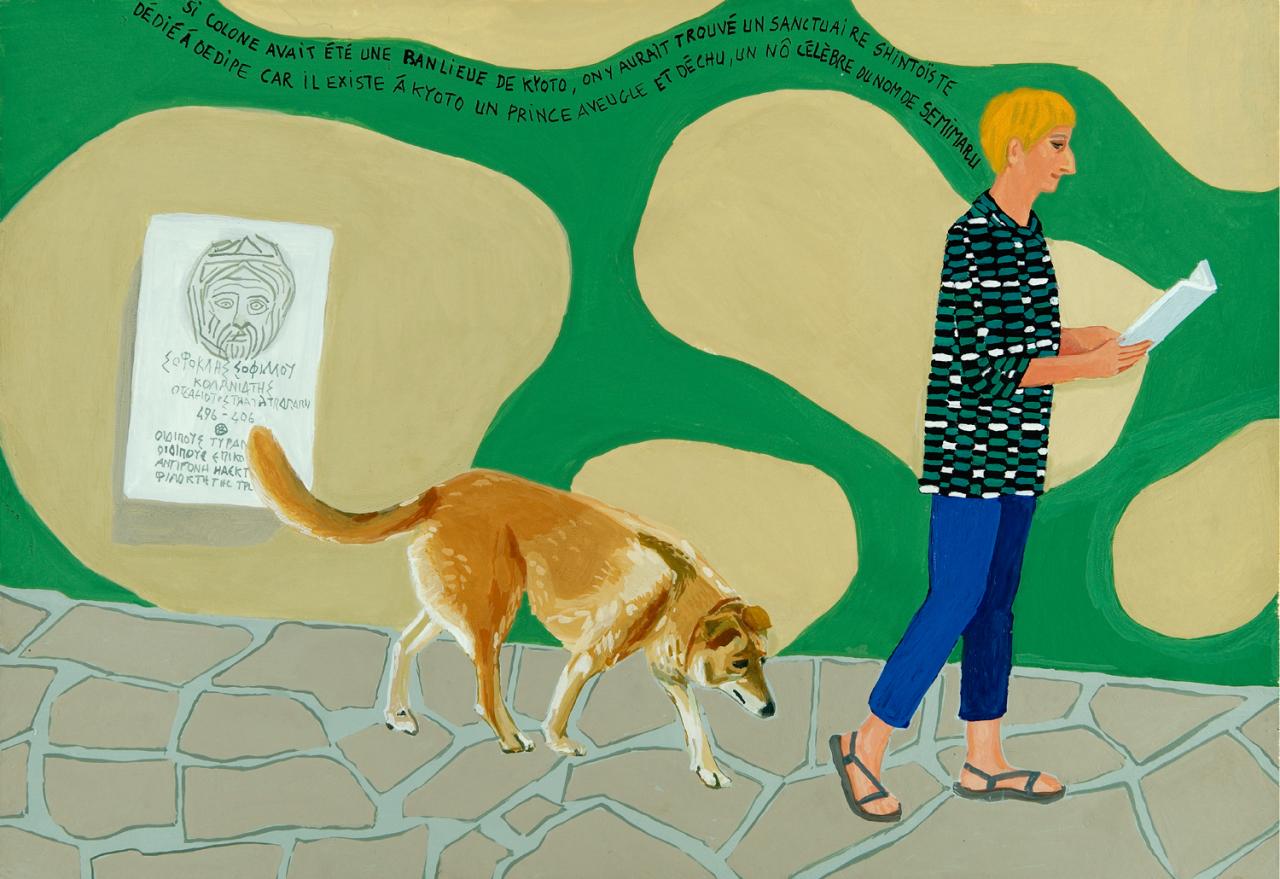

In her paintings, she also inserts words as dialogue, sometimes as images. “Allons” (Let’s go), “Vas-y” (Go ahead), “M’en fous” (Don’t care) — might be read on a T-shirt or in the center of a composition. Then there’s Le Songe (The dream), a sort of landscape in words, a life work, a project of twenty years. In a labyrinth, you read in connected captions: “Tout va disparaître” (Everything will disappear, “Peut-être pas” (Maybe not) “La poésie n’est pas dans la poésie” (Poetry is not in poetry). It is a spiritual landscape, as with Chinese painters, where you wander through forests and waterfalls. Her work might recall art brut or naïve art, only Mitout’s work is thorough, erudite, and precise. She recounts her life as a dream, from encounters to events: rehearsals of a play, a trip to Japan canceled due to Covid-19 (instead of the long-distance voyage, the artist visited the Musée Bonnard, near Le Cannet in the south of France). In her drawings of surreal scenes from a hospital during the pandemic, the ground of a parking lot resembles David Hockney’s swimming pools, although the composition refers more to a Visitation by Fra Angelico. She is currently planning to continue her work on vision and blindness, which she began with Œdipus and Semimaru, and the idea of the third eye, which will surely lead her to India, while the figures of Niki de Saint Phalle and Facteur Cheval make an appearance.

At every moment, her question seems to be: How do you find your place in a burning world? By generating joy as a form of resistance.

Written by Anaël Pigeat

Translated from french by Elaine Krikorian

1 This is a quote of Marie-Claire Mitout, interviewed by the author in Paris, on July 20, 2022. The quotations and factual details that follow are taken from this event.

Gouache sur papier, 21 × 29,7 cm

Photo : © Blaise Adilon

Gouache sur papier, 21 × 29,7 cm

Gouache sur papier, 21 × 29,7 cm

Photo : © Blaise Adilon

Gouache sur papier, 21 × 29,7 cm

Gouache sur papier, 21 × 29,7 cm

Photo : © Blaise Adilon

Gouache sur papier, 21 × 29,7 cm

Photo : © Blaise Adilon

Gouache sur papier, 21 × 29,7 cm

Photo : © Blaise Adilon

Galerie Claire Gastaud, Paris, 2021

Photo : © Margot Montigny

Galerie Claire Gastaud, Paris, 2021

Photo : © Margot Montigny

Gouache sur papier, 29,7 x 42 cm, septembre 2017

Gouache sur papier, 21 × 29,7 cm

Photo : © Blaise Adilon

Gouache sur papier, 21 × 29,7 cm

Photo : © Blaise Adilon

Gouache sur papier, 21 × 29,7 cm

Photo : © Blaise Adilon

Gouache sur papier, 21 × 29,7 cm

Photo : © Blaise Adilon

Gouache sur papier, 21 × 29,7 cm

Photo : © Blaise Adilon

Gouache sur papier, 21 × 29,7 cm