Frédéric Khodja

Depicting the monument of a melody in the pure sky.1

Uses of imagery

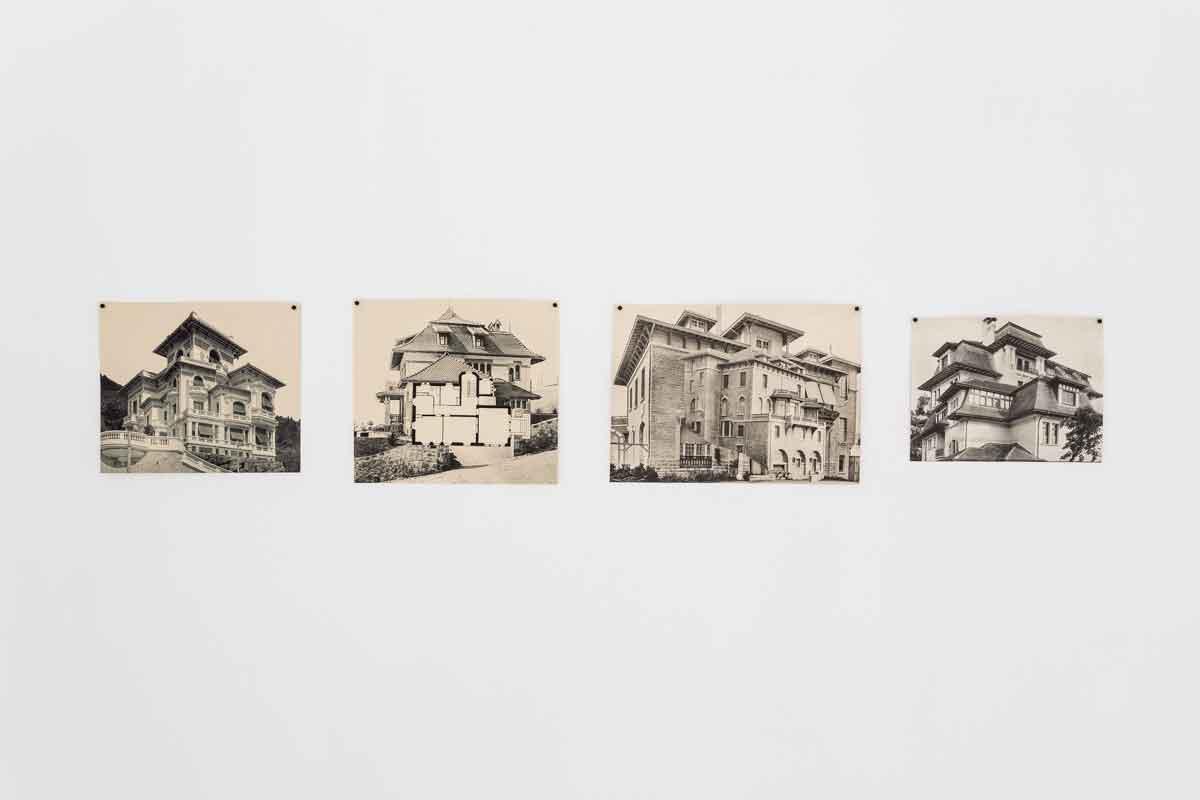

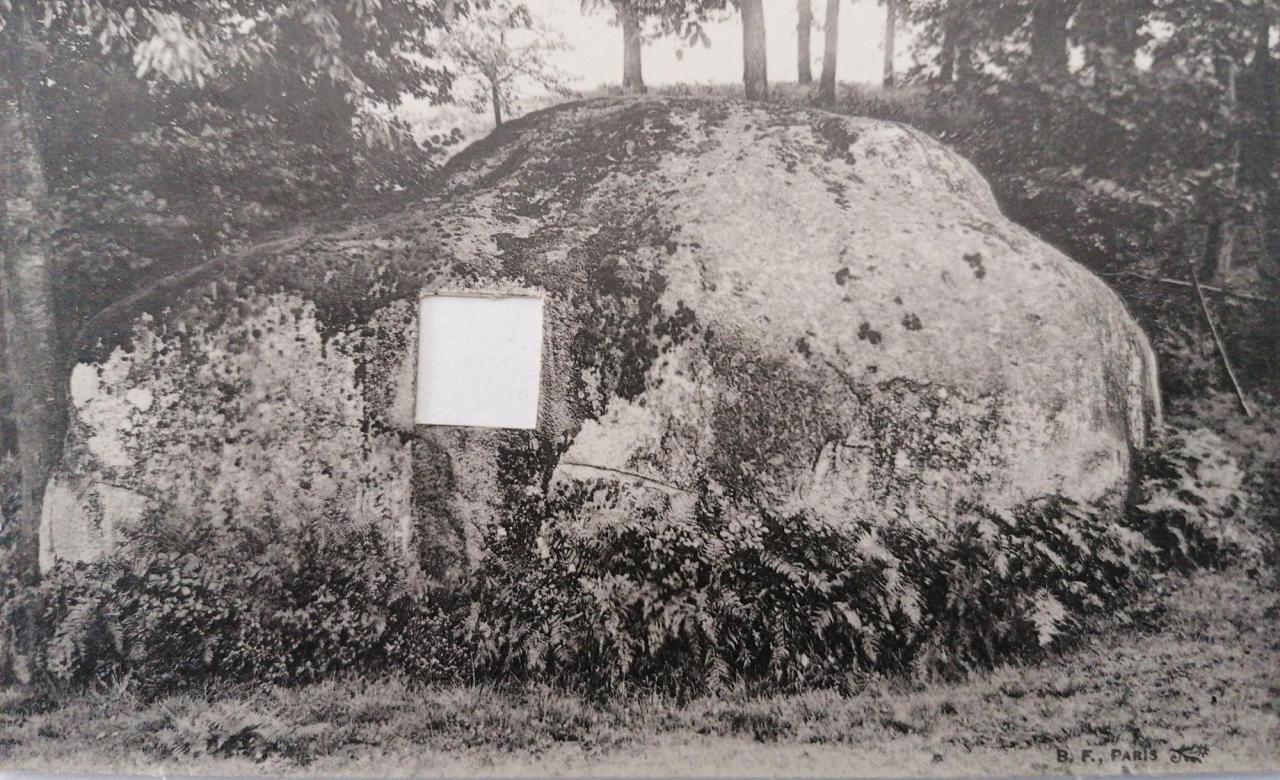

We are acquainted with Fréderic Khodja’s marked fondness for images, which he works and metamorphoses like a raw material. He may limit himself to “presenting” them in the laconic manner of Hans-Peter Feldmann2, or he may divert old post cards, making comparisons and forms of syncope at the heart of the image, cutting out blank areas, making changes in scale, and delighting in visual aberrations. Elsewhere, he adds words, fragments of narratives, as if suggesting that the photograph needs the clutch of language to express its potential.3.

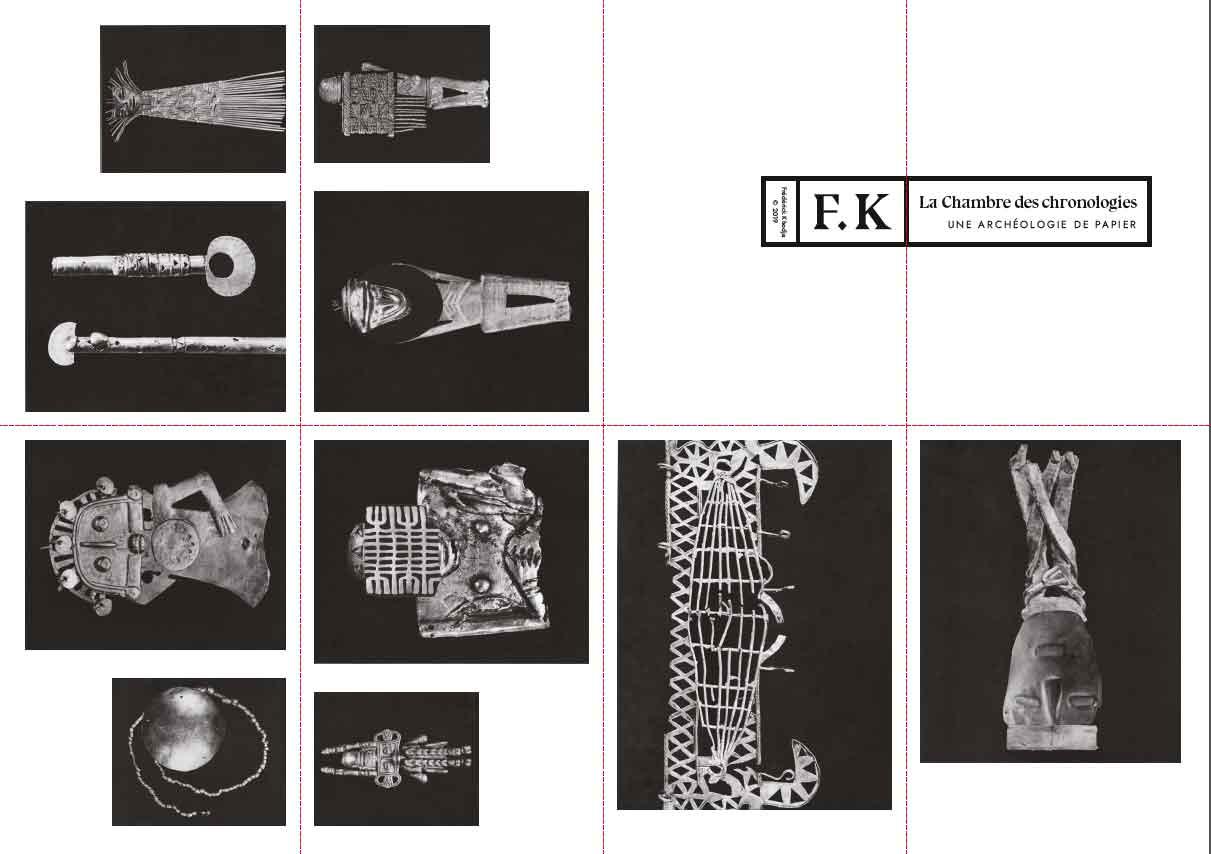

In a recent project, he deconstructs the discourse which overlays the image in certain scientific publications. Having brought together several ethnographic books, like a well-informed collector, he keeps just the photos, often black and white (masks, crests, tools, statuettes…) so as to re-print them individually on folded sheets of paper. This simple arrangement enables the reader to play folds and unfolds, and subtly organizes effects of progression and of surprise, the way an exhibition might.4. At times rounded off by drawing or collages, these reproductions of reproductions are cut off from their initial context. They elude scientific comment and classification which had previously assigned them a place, and come back to us in the form of disconcerting and powerful images, endowed once again with their native magic.

All these gestures and non-gestures around the image: presenting, combining, removing and adding, remove the image from its iconological unequivocalness. Over and above Frédéric Khodja’s natural inclination to arouse fiction, this part of his work reveals challenges of uses which are associated with the cultural history of the image, and which branch out in anthropological, scientific, memorial, informative and vernacular dimensions.

Reversible Panorama

These works involving the image demonstrate the constant nature of his interest in a form of narrative with a very specific economy, varied, not very talkative, and playing markedly with suggestion. Panorama, his series of drawings is part and parcel of this tradition.

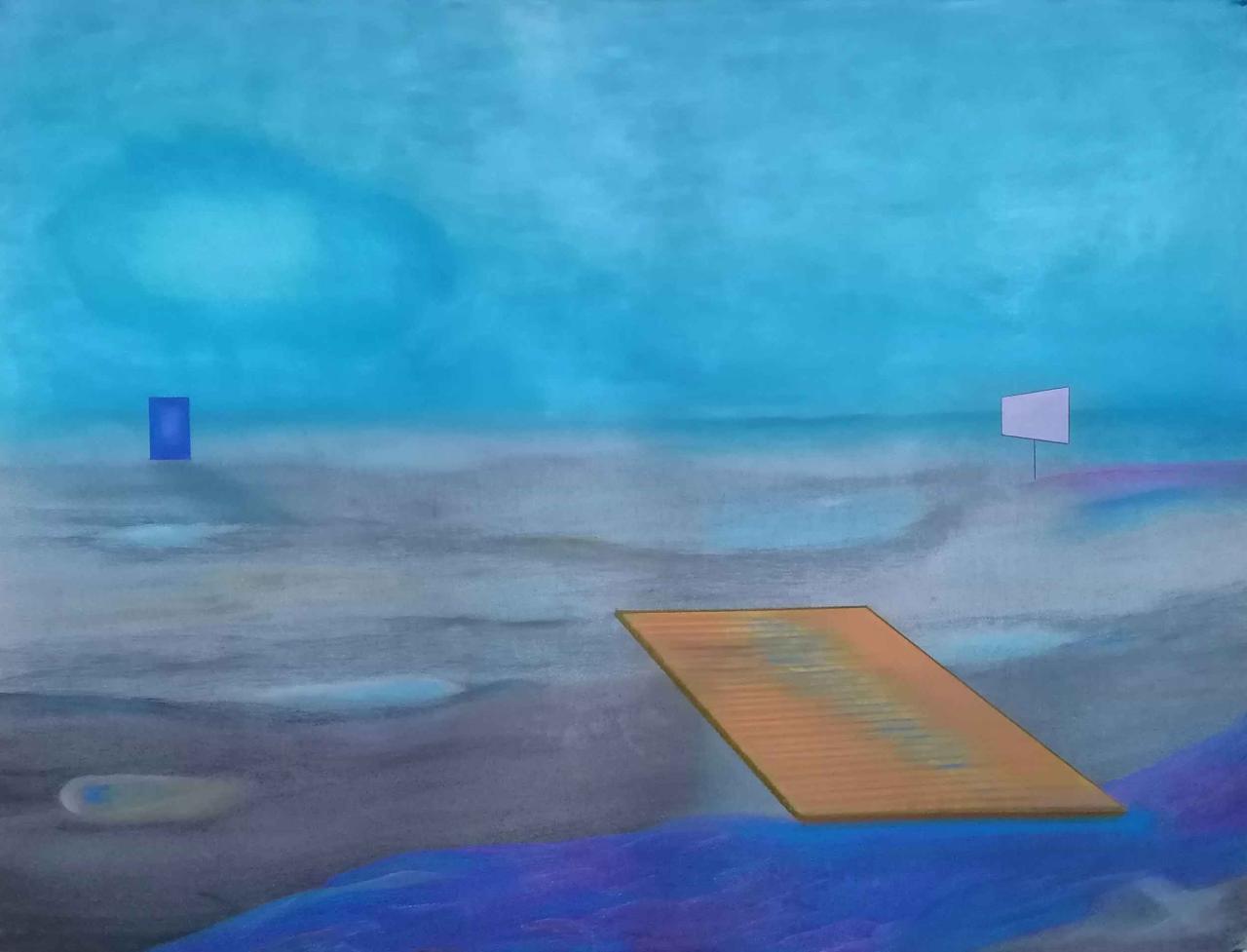

Frédéric Khodja has chosen pastel to construct this sequence of landscapes which immediately give rise to a sensation of displacement in colourful powders clouds. But these landscapes are formed by simple spatial indications of proximity and distance, and sky and earth. Sometimes masses appear and lend the scene structure: a waterfall, a cliff, a giant skeleton… Each one of these elements also appears in its substance, which is to say like a graphic gesture; stone walls, and piles of kelp may at any given moment once again become combinations of gestures with chalk, and the faraway cliffs can re-assume their nature of vertical grooves.

This factor transposed to literature conjures up Borges, and the Tlön territories he imagines. Over there, places owe their existence to the way we frequent them: “There is the classic example of a doorway that existed while a beggar huddled in it, and which we lost of see when he died. Sometimes birds or a horse have saved the ruins of an amphitheatre”.5. We find ourselves imagining that the Panorama landscapes produce this Borgesian marvel, taken from a state of oblivion by the power of a thought.

Force of appearings

This relation involving the reversibility of the figure, somewhere between trace and figuration, and very perceptible in these colourful surfaces, is not common to all painting and drawing. Nor does it tally with a pareidolic6 quest on the part of Frédéric Khodja, because the environment is not abstract, and as a result it does not offer an infinite array of interpretations.

Looking at these drawings is to sense the patient wear of the chalk by paper, which ushers in this reversibility; it is to discern the slow merger of colours by shading, and their progression until they have covered the surface. It is also to galvanize your attention onto incidental forms emerging from the chalk, which the artist has accommodated and even named: they are, he says, “appearings”, and some of them will keep their lack of definition: small marks scattered in the sky, areas of contrasting colour, a floating rock, pebble-clouds…

In a subtle dialectic, landscapes and appearings gather together because painting has this power to restore invisible forces. Landscapes project us into the sensation of overflying, to be sure, and they represent nothing less than an experience of the visible.

But the strokes of chance reveal a network of energies which dominate the thing represented. These haphazard marks, discreetly slipped into a figurative world, bring a break to our attention. They powerfully evoke what Francis Bacon called the diagram: that moment when accidental forms surge forth, “removing the picture from the optical organization which already reigned over it”; marks, or “meaningless” lines which, as Deleuze would put it, give rise to the truly pictorial experience.7

These blurred landscapes and their appearings are thus the initial stasis of the Panorama drawings; anecdote-free landscapes, where gesture and colour combine the conditions of an illusion and pull it at the same time towards underlying forms of pictorial energy. The artist puts it like this: “the reason for the landscape is […] to accommodate the gaze, be it mine or the onlooker’s; accommodate it to permit me hesitation, wandering, reversal, the pertinent and the non-pertinent…”8

Objects of geometry

As if hailing from a parallel history, strange geometric figures are installed in landscapes, panels on legs, rectangular surfaces represented in perspective, or simple vertical lines. They cut and decide—in all senses of the words—in this atmosphere of figural indeterminacy; their sharpened outline seems to visually cut up the surface.

From one drawing to the next, one or two constant features borrow and slightly alter the scenes, bringing us an intoxicating floating feeling, even into the well-oriented figure, as if seeking a passage from sign to textuality. Jérémy Liron referred to his visual link with writing in other drawings produced by Frédéric Khodja: “The punctuation they erect”, he wrote, “makes them look a bit like typed characters; those we find more and more rarely on a typesetter’s compartmented tables, or on upholsterer’s tip-ons and punches”.9

Do these geometric objects organize space through their perspective? Partly, but it would seem that they have a different function. Like objects hatching, they introduce the event of a narrative waiting for characters, bolstering the dreamlike and inhabited atmosphere of this series. Dreams, or memories are probably among the ascendants of this gentle and persistent set. One after the other, the drawings perform a repetitive score linking chromatic space to geometric objects, as if to summon a matricial memory which is strengthened in this fragmentation. In Temps et récit, Ricoeur talks about an untold story that lies at the root of the psychic subject. Within us, we apparently have a quintessential narrative structure which is in abeyance, and forms us.

The evanescence of these landscapes, and the enigmas they present undoubtedly leave room for narrative, a very imaginary form of narrative, which goes as far as fantasy. It is not surprising that some of the literary references called upon by Frédéric Khodja veer towards magic realism: Bioy Casares, Silvina Ocampo, the scape of whose imagination is rooted in fragments of reality, and the Melville who wrote The Veranda, which develops ever more forcefully both specularity and visual illusion.

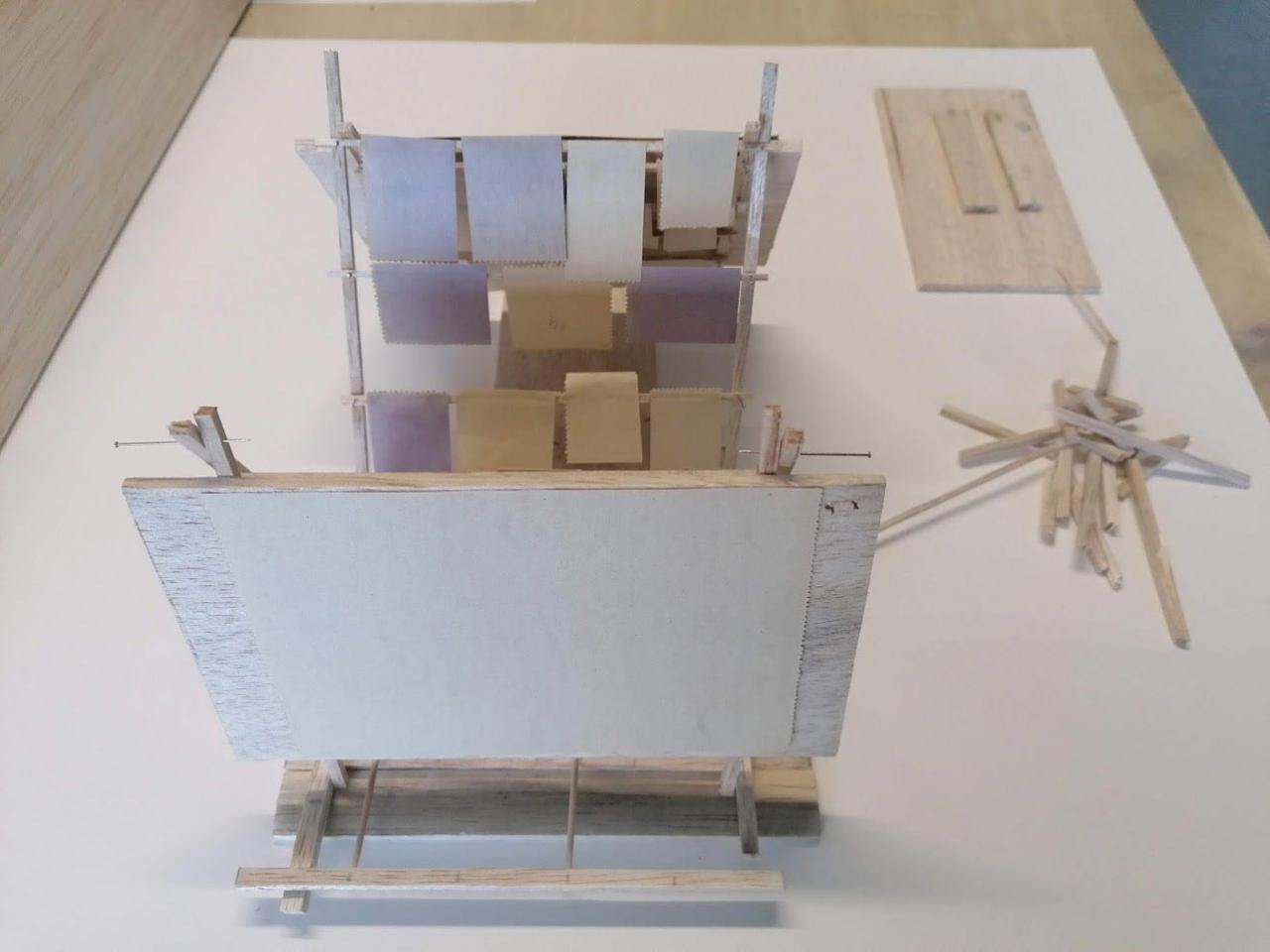

This marvellous idea put forward by Borges, to describe the world of thought which is common currency in Tlön, required that we only put our trust in perception, without having recourse to reason. It is latent in the strange easel devised by Frédéric Khodja to present Panorama. This human-scale piece of furniture seems to come straight from the drawings, so neatly does it overlap with the form of the screens scattered in the landscapes. It offers a system of seeing as much as a hanging solution: christened “FRED” (Fire Raft Screen Drawings), it offers a flat surface for presenting works, front and back, with wires stretched at several parallel levels behind, like wash lines. Small tiered drawings playing with a large drawing on the vertical surface create a place of volumetric confrontation for all the drawings.

If we have grasped to what degree the Panorama drawings are linked together by a set of common methods, we can note here that they “have to do” with each other. Together they form a roundabout of drawings to be visited and they multiply the viewpoints, detaching our vision from its one-sight habitus. Some of the small drawings are pierced by cut-outs which form a frame and a view of what lies behind… The artist accordingly talks about “meta-drawings”, thereby opening up something beyond the drawing veering towards many lines of thought. Never the same vision, never the same narratives… FRED the easel-screen emerging from the landscape breaks up the manner of our gaze, accustomed to the phatic images described by Paul Virilio10 in his day, those images which have their say and shape our vision. A fine harbinger of a work that becomes the vehicle of a surpassment.

Notes :

1. Paul Valéry, Eupalinos, Gallimard, 1921. “Je veux entendre le chant des colonnes, et me figurer dans le ciel pur le monument d'une mélodie”. In the realm of the Dead, Phaedra finds Socrates, injured as he contemplates the river of Time. He reminds her of the memory of the architect Eupalinos, builder of the temple of Artemis, with whom he was associated, and who, in her own words, managed to “make buildings sing”.

2. In one of his exhibitions, Feldmann asked that these words be added above the text: “Please don’t read the text. Enter and look for yourself, you are old and intelligent enough. You don’t need anyone to explain the world to you.” Collective La bonne adresse - Exhibition Hans-Peter Feldmann, La galerie des Galeries, 2016

3. A selection of these collages was published in Prêts de fiction, in the form of two boxed books enhanced by a signed digital print. A/over, Saint-Étienne, 2016

4. Frédéric Khodja, Sept archéologies de papier, boxed folded sheets of paper. Graphic design: Perluette & Beaufixe, 2019

5. Jorge Luis Borges, Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius in Fictions, Gallimard, 1974 trans. Paul Verdevoye

6. Pareidolia: figurative interpretation of a seemingly abstract form.

7. Gilles Deleuze, Francis Bacon Logique de la sensation, Seuil, 1981

8. Whim-Wham, Interview with Paul Sztulman, Journal Hippocampe n°9, July 2013

9. Jérémy Liron, Sous le regard, 2012

10. Paul Virilio, La machine de vision, Galilée, 1988

Vue d'atelier, sur mur de dessins d'étude

Vue d’atelier, dispositif recto sur le meuble FRED, 2021