David Falco

In Between

David Falco’s oeuvre is invariably the site of a noiseless spectacle, a shift, a dream, … Here, we are living superficially in an everlasting telluric world. Out of our conflicts with the “natural”1 world, the artist creates a theatre, subtly emphasizing the dissonances of our way of being in the world. Human projections, for their part, are broken on the slope of a more grandiose reality.

Like tectonic plates which, in an age-old movement, inexorably collide, David Falco organizes the collision of domesticated space—thwarted, subordinate—with natural space—insurmountable and sublime. Mountain origins have lastingly imprinted in the artist’s mind the motif of that mountain which tirelessly paces his work. It is probably a ground-breaking shock to see the last unknown territory fallen into the space of rationalizations and short views.

Spitzberg 78°15' N 16° E (2005-2008) is nevertheless a name which rings out like a promise of adventures on the outer edges of the world.

In this series, which is the oldest and possibly also the closest to an accepted romantic meaning of landscape, Falco confronts the dreamed image of a territory with his realities. It is thus a scarified landscape, hostile and grandiose, and almost lunar, that is revealed, well removed from hackneyed images fantasized even by the inhabitants of its farflung spaces.

Often, as here, the artist questions the observation process and plays with codes of landscape, differences in representation, fantasies about the world, and our way of living in it. Putting himself in an exploratory position, David Falco tries to reveal the immutable forces made fragile by the action of a person not very aware of his forms of belonging and his dues.

In Corps étranger/Foreign Body (2012-2020), we immediately understand hostility, and the rejection of what is different. The foreign body is what is accommodated without being invited, and what penetrates an inhospitable environment.

By associating expressions stemming from grey2 literature with the territories he photographs, David Falco re-contextualizes often transitory spaces, vehicles of ambiguity about their function and their future development.

By endowing them with new functional qualities, and by potentializing their capacity to adapt to the user needs of our contemporary societies, the artist reveals the mechanisms of appropriation which circumscribe the boundaries of a world obliged to change, where every space must justify its “usefulness”.

What is the foreign body here? That of a person who has already been long imagining the natural world as a space to control? Probably.

From his professional past in contact with printers and retouchers, David Falco would retain attention to detail, to the object, to the subtlety of grain, to the process which governs the appearance of the image. What will remain of that of the librarian is the liking for the recollection of subtle references to the history of images.

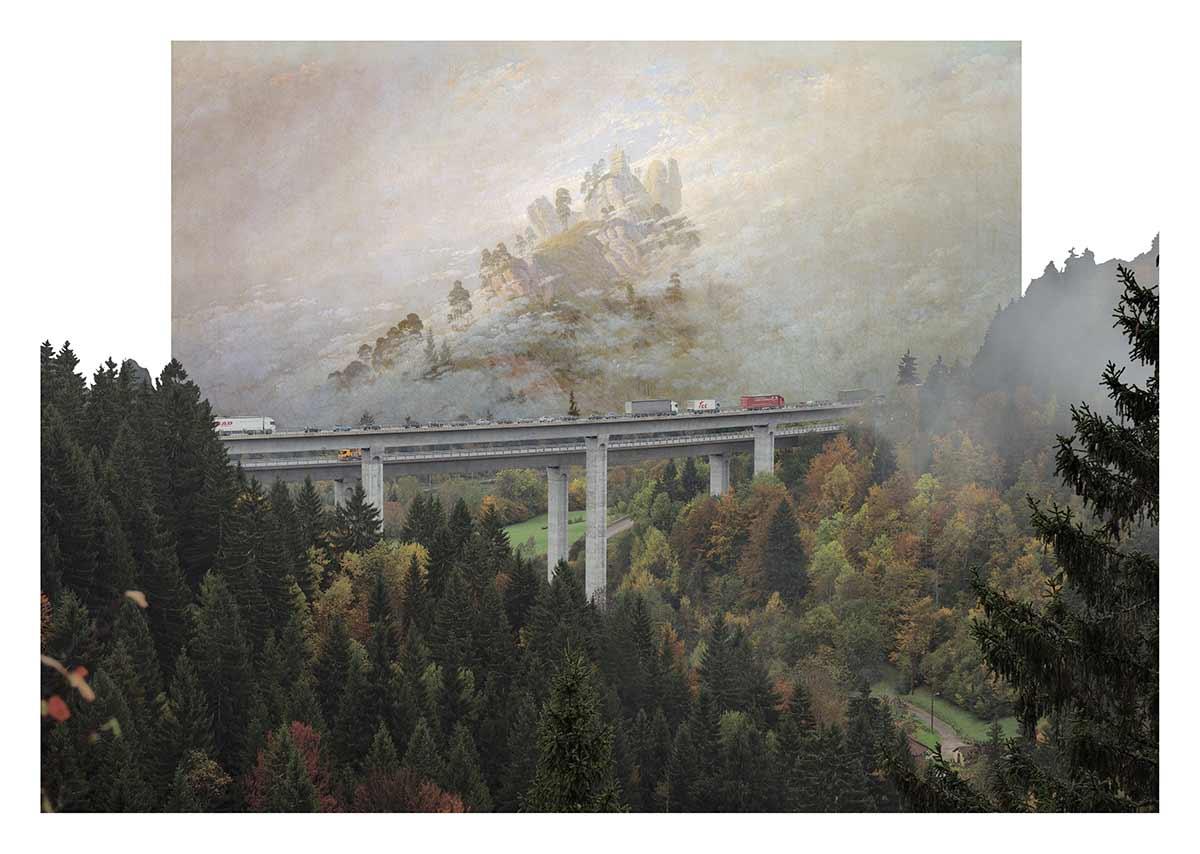

The same goes for Entre-temps, après Caspar David Friedrich - 1774-2019, where the artist has been forcing himself for almost twenty years to make a re-reading of the oeuvre of the German painter.

Through a subtle interplay of photomontage, Falco hybridizes many different sources, high definition of Friedrich paintings and current imagery. In these “layered” landscapes, two time-frames collide: Friedrich’s, which is idealized, and the snapshot one of our uses of the contemporary world. Here the artist advocates the idea of a “double vision” being overlaid on reality. He often proceeds in this way using an image, the way he would so with a palimpsest, and in subtle interplays of collages, scales, associations of ideas, and formal or temporal superpositions…he gives rise to the creation of new readings.

Time, which is a central concern in David Falco’s oeuvre, is a time which keeps us in suspense, between two worlds, on the threshold of the catastrophe patiently waiting for us. We find ourselves entangled and caught up in the layers of a space suspended at the intersection of immemorial time-frames and immediate time-frames. As in Paysages avec figures/Landscapes with figures (2015), where what appears as the futile gesticulations of everyday human activity is superimposed on the picture of age-old landscapes, which have become hubs of local tourism.

In Lapiaz (2015), an image.

One of ancient rocks, fashioned by time and bad weather.

We topple, astray somewhere in the irregular forms of a space with uncertain scales, astray in the time-frame of this animated image which silently changes before our eyes. Shadows which run across it, at times like caresses, at others disconcerting, reveal it as a theatre curtain would do. Borrowing on his own behalf the romantic definition of the sublime, David Falco organizes a loss: a loss of formal references, temporal references, and scales.

Dizziness of heights, the summons of the abyss; and the feeling of being there, on the ridge, ready to fall.

Loss of references and landmarks again.

In Sad Landscape3 (2012-2017), are we high up in mountains? On a hostile planet? In a Méliès set?

Without managing to discern whether the night or the day are offering their crepuscular light to the revelation of a theatre of motionless violence, what seems to us to be a series of desolate mountainscapes calls to mind the tormented rocks peculiar to the paintings of Patinir.

Yet there are no mountains here, but formations caused by the stagnation of rain water and the nitrates resulting from intensive farming. In the ditches and along the tracks of the Poitou countryside, periods of warming followed by drying up thus imprint by sedimentation a vegetal gangue, suffocating for the endemic flora it colonizes. In the presentation of these suffocated micro-spaces there surfaces a desire, to reveal a form of “potential” landscape, at once grandiose and tiny, immutable and finite, indestructible and reduced to the state of dust.

Archaeologies of the future, divinations of the past: interdependencies which link times and spaces, and which thus involve the artist in an ongoing re-reading of his work.

This superposition of the time-frames of artistic research, their overlap with the time-frame of the world, offers glimpses of the possible formal changes of an oeuvre that is forever developing. David Falco’s “potential” images, at once destabilized and solid, question us about our relation to the “wild” world, and invite us to shift our gaze. Moored to the ground, they exhort us to “re-solidify” our relation to the world, and take cognizance of resistance in the face of the erosion of a world that has become liquid 4.

Notes

1-We shall here mention the calling into question of the clash between nature and culture introduced by western societies, based in particular on the writings of Philippe Descola: “If we recognize that the largest part of humanity has not, until recently, made definite distinctions between the natural and the social, or thought that the treatment of humans and that of non-humans stemmed from entirely separate arrangements, then we must envisage the different kinds of social and cosmic organization as a matter of distribution of what exists in collectives: who is put with whom, how, and to do what?” (Philippe Descola, Par-delà nature et culture, Gallimard, 2005).

2-Grey literature defines the category of documents, be they paper or digital, which do not result from so-called commercial publishing. It consists essentially of scientific, administrative, industrial and commercial documentation.

3-The title Sad Landscape is a direct reference to the series and publication of the same name initiated by Joseph Sudek in the mining regions of the north of the Czech Republic in the 1950s and 1960s.

4-The liquid society concept runs through a significant part of Zygmunt Bauman’s philosophical oeuvre. In it he defines the concept of liquid modernity, as opposed to that of solid modernity. The “liquefaction” of contemporary society is here thought of as an outcome of neo-liberalism, “progressive erosion […] caused by the space-time compression that is typical of globalization.” (Zygmunt Bauman, Le coût humain de la mondialisation, Hachette, 1999).

Block error: "DOMDocument::loadHTML(): Argument #1 ($source) must not be empty" in block type: "text"

Série Spitzberg 78° 15’N, 16°E

tirage jet d’encres pigmentaires sur papier Fine Art Pearl

30 × 30 cm x 4 cm (encadré)

Série Spitzberg 78° 15’N, 16°E

tirage jet d’encres pigmentaires sur papier Fine Art Pearl

30 × 30 cm x 4 cm (encadré)

Série Corps étranger

digital C-Print, Lightjet, satiné

40 x 50 x 3 cm (encadré)

Série Corps étranger

digital C-Print, Lightjet, satiné

40 x 50 x 3 cm (encadré)

Série Corps étranger

digital C-Print, Lightjet, satiné

64 x 80 x 3 cm (encadré)

Série Entre-temps, après Caspar David Friedrich, 1774-2019

digital C-Print, Lightjet, satiné

105 x 148 x 15 cm (encadré)

Série Entre-temps, après Caspar David Friedrich, 1774-2019

digital C-Print, Lightjet, satiné

54,9 x 73 x 3 cm (encadré)

Série Paysages avec figures, 2012-2020

Vidéo, 6 min 25"

Vidéo, noir & blanc, sil. 11' 25"

Vue de l'exposition Rassembler, Lavitrine, LAC & S, Limoges, 2020

Vidéo, noir & blanc, sil. 11' 25"

projection vidéo, dimensions variables

Série Sad landscape

80 x 100 x 3,5 cm (encadré)