Ben Saint-Maxent

Making the shadows bloom

Allow me to begin, before circling back to Ben Saint-Maxent, with a detour through another artist, a bit removed from our subject. A few years back, French artist Camille Henrot held an exhibit at the Kamel Mennour Gallery with a title that, having piqued my curiosity at the time, I remember quite well. Her title asked, “Is it possible to be a revolutionary and like flowers ?”1 (she received the prestigious Silver Lion at the Venice Biennale a few months later). At the gallery in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the question found a possible answer as a set of ikebanas, those complex Japanese floral compositions, each of which referenced the work of an author who, in the artist’s words “takes an ethical look at the world while taking the world in hand.”2 Despite the eloquence and charm of these still lifes combined with different types of ordinary objects (pipes, cinder blocks, more-or-less designer pots…), about all that remains to me of this exhibition is summarized in the interrogative title and its clever association of concepts. As Vinciane Despret would say, here we find a “good question”: one we hadn’t quite thought to ask ourselves but which, once formulated, gives us food for thought. How, admittedly, can one indulge in such a seemingly futile passion without hindering the rectitude necessary for the expression of radical political thought?

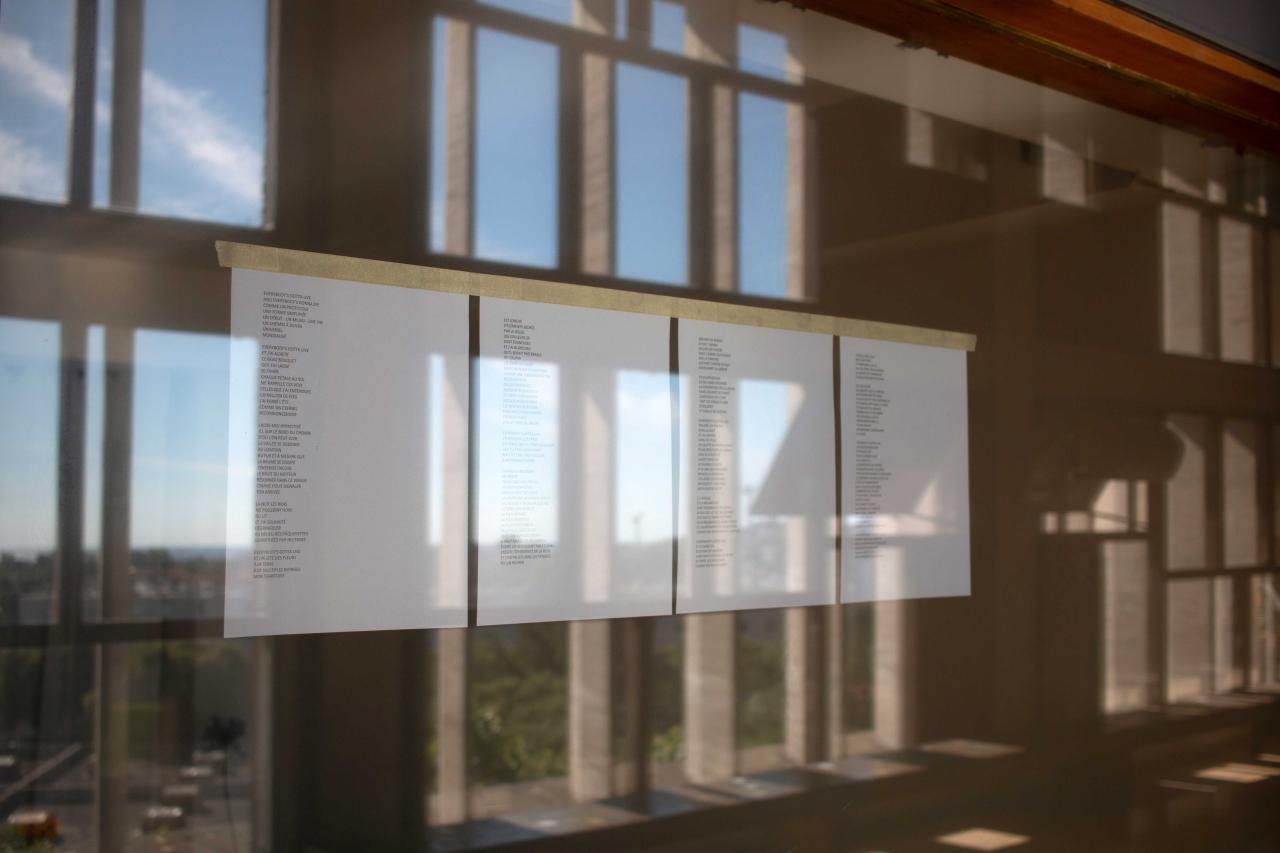

I don't know if Ben Saint-Maxent is revolutionary, but I truly believe he takes an ethical look at the world, in no way stopping at a complacent stance. I also know that he likes flowers. In fact, he likes them so much that he puts them pretty much everywhere: on social networks, where he often adorns himself in their colorful finery under the pseudonym Tournesol Ben (Sunflower Ben), in his e-mail signature, on his website whose cursor is a stylized daisy, in his small garden nestled upon a hill in Marseille’s Belle de Mai neighborhood, and of course in his exhibitions, the most recent of which, “Everybody”, in a well-lit space at Marseille’s Cité Radieuse, consists of just this, an exhibition of flowers. I won’t attempt to describe their types, from afar they seem rather common, despite their size, the kind you pluck at roadsides in the summer. In the role of vases, their thick stems protrude from old, vertically-positioned sneakers, penetrating the heel counter to lodge within the tip. Something of an unnatural graft occurs in this alignment, obviously one of living material thrust into an industrial accessory destined to be the brand-name casket of its desiccation; and one of urban culture infiltrated by what might be called the pastoral, organic realm that it represses. But rather than an aberration or settling of accounts, what the artist seems to offer here is more like a tribute. Attesting to this, a poem in capital letters is taped to the windows opening onto the exhibition space:

I’VE MADE OF SOLITUDE

A FRIEND

EVER SINCE MY BROTHERS

LOST THEIR WAY

IN THE SPECTACULAR

THE EXIT BY THE MAIN DOOR

IF THERE’S TO BE JUST ONE

WILL BE THE MOST BEAUTIFUL

MOST INTENSE

MOST INVENTIVE

MOST STRIKING

WILDER THAN WHAT

WE SEE IN THE MOVIES

WE MUST MAKE A MARK

WRITE A STATEMENT IN BLOOD

SHATTER THE EPHEMERALITY OF THE ROSE

AND CARVE A PLACE IN THOUGHT

LIKE STONE

Thus the shoes bloomed to commemorate presences we know nothing about, now symbolically stranded in the exhibition. In a similar way, a few months earlier, capsules of nitrous oxide bloomed, strewn across the ground of the installation: “Adieu la Poésie.” There was no celebratory verticality this time: the capsules, reworked as mini water vases, had been returned to their usual post-use abandon. The video that played in the background, with music composed by Saint-Maxent recalling lapping, muffled techno, showed images of a free party, with speakers placed around it making the same reference. In the projected image, closely-framed dancing bodies form a motley, anonymous congregation offered to the universal gestures of the party, one in which the general atmosphere of the installation did not seem to fully participate. Was this due to the rhythm, out of time, which made the arms and legs in the video swing without establishing connection to the music? Or was it the red light that enshrouded the space, giving the aluminum capsules a glowing reflection? The artist’s words were once again posted on site, underscoring the melancholy and inscribing the work within a memorial register.

YOU MIMIC MY MOVEMENTS

LIKE A GHOST

I DANCE HABIT

AND NOSTALGIA3

If in this work, as in the most official ceremony, the flowers come to mark the perennial trace of memory, they are no less linked to a set of objects that rarely serve as substrates for commemoration. The old sneakers Saint-Maxent finds along his road home, and laughing gas dispensers that litter gutters, show up as ordinary aspects of a certain of youth. A youth which he is obviously no stranger to, one he isn’t mocking but rather signaling intimacy with. It is perhaps at this site of the intimate, or more precisely, this guileless affective proximity, that the artist’s work distinguishes itself from that of the more pretentious or grandiose. In this way, along with a growing number of artists currently observable on the French art scene, he belongs to a generation for whom formal stakes are in service of a more or less affirmed expression of that which unites them to their circumstances.

Of course artists are de facto permeated by their era, and the color of the times operates within a work in various ways without its being the object of a clear stance taken by the artist. The circumstances I’m referring to then are those of a present that’s lived and shared with all of those who constitute a community, without bearing its name, but with which new ways of grasping daily life are continuously being created. There are as many critical propositions as there are different ideals than those which society, as we still largely know it today, was founded. But rather than in distant considerations, it is through daily commitments and sustained attention to their human and environmental circles that these artists and their practices devote themselves.

Back to the flowers. When we met, Ben Saint-Maxent spoke of the above-mentioned garden, not so much to tell me about the different species he planned to grow there (had he already noticed my ignorance of the subject?) as to discuss his desire for autonomy. Indeed, for Saint-Maxent, who relies so much on flowers in his work and outside of it, turning to specialty shops was, in the majority of cases, neither economical nor a coherent ecological choice. Thus, his declared purpose in continuing his installations is to fill them exclusively with flowers that he’s grown himself—a concern about independence that joins the one of using what is closest to him and touches him most directly. This should not, of course, be taken as the unfortunate or narcissistic expression of turning inward. On the contrary, it’s a modest attitude adopted by an artist whose work does not intend to solve the problems of the world, but rather to understand the place he has chosen to occupy in it.

A final turn through Saint-Maxent’s poems, after consulting the notes I took during our different encounters, leads me to pick up a book whose cover—let’s stay on topic—displays a picture of a dandelion. Above the fragile white flower is another question, more important than the one that introduced this text, asked this time by philosopher Judith Butler: “Can one lead a good life in a bad life?” I turned to this work because it seemed to describe a line of questioning with which the artist, as well as anyone with morals, confronts himself. But also because it seems to me that through his work, Saint-Maxent speaks, more often than we’re used to, to these lives that earn so little attention, lives that Butler calls “ungrieved.” An ungrieveble person, in Butler’s words, “already understands him- or herself to be a dispensable sort of being, one who registers at an affective and corporeal level that his or her life is not worth safeguarding, protecting or valuing.”4 She later clarifies that we shouldn’t think the ungrievable won’t be mourned by their loved ones, but that such mourning will only take place within the “shadow-life of the public,”5 that is, where their existences had already been relegated. This, I believe, is what Saint-Maxent’s work attempts to address. It tries to shed light on these shadows and, like cultivating relationships with these precious beings, maintain a garden.

Notes :

1 Camille Henrot, “Is is possible to be a revolutionary and like flowers?”, Kamel Mennour Gallery, Paris, from June 9-10, 2012

2 Translated from the French article at https://slash-paris.com/articles/entretien-camille-henrot

3 This excerpt, as well as the previous one, can be found in full at: documentdartistes.org

4 Judith Butler, “Can one lead a good life in a bad life?” Adorno Prize Lecture, Frankfurt, 2012, (Qu’est-ce qu’une vie bonne ?, Rivages poche, Paris, 2020, p. 54).

5 Ibid.

Translated by Elaine Krikorian.

Dimensions variables, installation, sneakers, fleurs, soclage, texte

Dimensions variables, installation, sneakers, fleurs, soclage, texte

Dimensions variables, installation, sneakers, fleurs, soclage, texte

Dimensions variables, installation, sneakers, fleurs, soclage, texte

Dimensions variables, installation vidéo, système son, fleurs, capsules de protoxyde d’azote, lumière rouge, texte

Dimensions variables, installation vidéo, système son, fleurs, capsules de protoxyde d’azote, lumière rouge, texte

Dimensions variables, installation vidéo, système son, fleurs, capsules de protoxyde d’azote, lumière rouge, texte