Anaïs Touchot

Anaïs Touchot is an artist the way Michel Onfray is a philosopher: eight hours a day, five days a week, minimum. And she addresses the task in a conscientious way.

Such an observation might seem trivial for those still dreaming about the romantic definition of the artistic genius who is misunderstood and tormented. This definition tallies much better, however, with the reality of students graduating from Schools of Fine Art: their status is not promoted, and their value is not remunerated—and they have to work unflaggingly in order to make their contribution.

It is strength of will that shows through when Anaïs Touchot produces a work. The physical strength of a woman handling a mass in order to destroy; and the mental strength of a woman who is forever improving her work. Si j’étais démolisseur is not a performance. Nor is it a sculpture. It is a moment which she regularly repeats. While an exhibition is being put up, she constructs a wooden hut. On the evening of the opening, as at the CAN in Neuchâtel, she destroys it. Then throughout the exhibition, during opening hours, she reconstructs, only with what is there—with whatever is to hand. Without adding more nails or planks. And when evening comes, she relentlessly demolishes her construction. The better to give it back a form on the morrow. Needless to say, Anaïs Touchot derives a great deal of pleasure from developing the structure which is continually evolving: outwardly, we can nevertheless see her task as being like that of a contemporary Sisyphus.

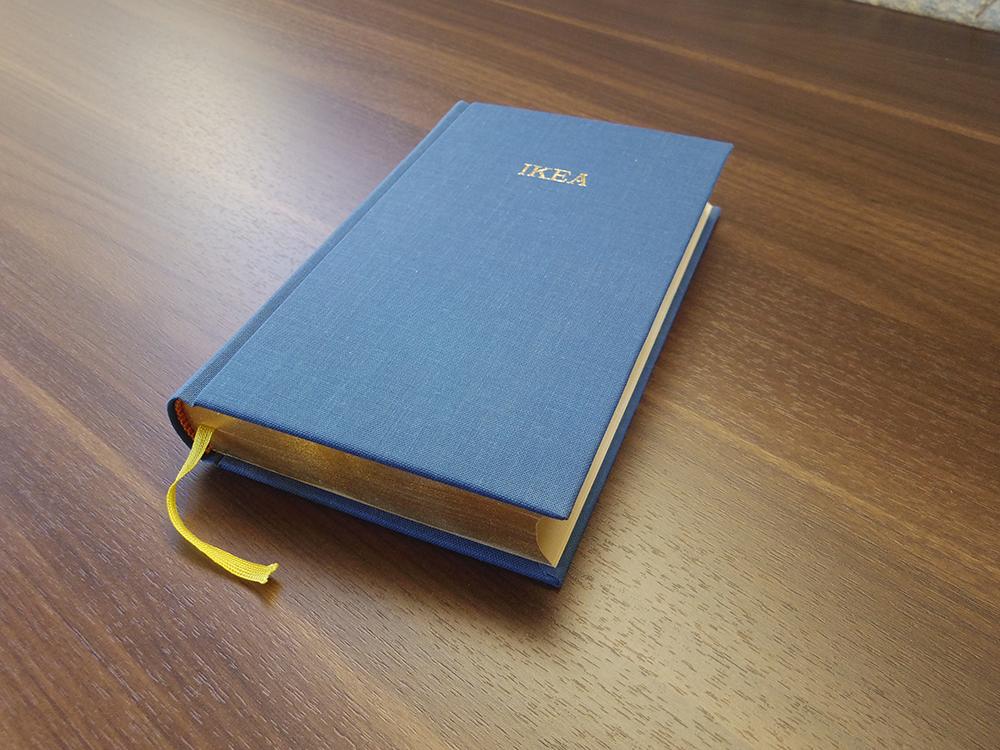

But what did Sisyphus produce every day when he pushed a rock to the top of a mountain only to see it roll back down the other side? Really nothing? Tireless work is first and foremost an expenditure of energy. And, in Anaïs Touchot’s case, this expenditure permits not only an assertion of values but also the possibility of an encounter. “Values”: let us dare to use this word, because it is in such bad taste to bring it up in an age of unbridled liberalism. When, for hours on end, she recopied an entire IKEA catalogue before having it printed in the form of a missal to underscore the move of Sunday church gatherings to sheds full of cheap furniture, her output smacked of an attachment to nowadays ‘has been’ values: research, vernacular knowledge, merit…

Her production thus enables her to be joined by much of the populace, people living outside capitals who will not necessarily visit exhibitions. Those to whom, in the end of the day, nobody has ever really explained the status of “artist”. These people recognize her activity and accept it, because, as she keeps to office hours and makes a quantifiable effort, then “it is definitely work”. Anaïs Touchot has found the place where encounter is possible. This is the case when she asks people in her Breton entourage to bring her patatoes , or when she builds a hut, especially outdoors. “With huts, everyone tells their own little story.” So a more personal relation can be woven based on a shared anecdote.

But this hut motif is not insignificant. In addition to its environment-friendly character, with its recycled materials and is construction involving very spare means, it carries within it the great question of our century. We referred above to the philosopher from western France; he recently published a book about the life of Thoreau, an American thinker who, it just so happens, shut himself away in a hut deep in the woods. Like Anaïs Touchot’s works, they raise the question about the possibility of living a synchronized life within an ever more registered and charted society. How can you “live a philosophical life” when you live in a megalopolis? This question, which is deeply linked with that of freedoms, must really be scary; this is attested to by the threat of destruction that floats over the huts of Saint Brieuc (nevertheless witnesses of the History of the first paid holidays) and still worries the huts belonging to fishermen in Provence.

Anaïs Touchot’s works are invariably made on a human scale, and encourage the relations which Man has with his peers. The ones she produced—not without problems—in Colombia do not dodge this rule. Everything started with an invitation to take up a residency on the Caribbean shores of Colombia. As soon as she arrived, her status as a woman—and a white woman, to boot—turned her just as much into an easy prey as into a being with little hope of being taken seriously. All creative work became extremely fraught; with the exception of a feminist feeling which, for the first time, would take a more militant form. How are you meant to arrange a meeting when you have to stay shut away for safety reasons? How can you produce things when there are no materials to be retrieved, because they have all already been retrieved by people plying that trade? How can you find a subject which affects people beyond cultural differences?

Anaïs Touchot sees in body-building a way which opens up avenues of responses. Her analysis of fitness is especially subtle: over and above being a question of statuary, looking at the body is a worldwide preoccupation. It is also one of the rare places where a women can show virility. The idea of opening a gym started to take shape: authorized virility, togetherness, friendship and cohesion were forever being emphasized. It was at that moment that it was proposed that she give a lecture. She arrived with T-shirts which she had flocked, with the idea of creating a group. The participants put them on, and a discussion about love, fitness and art got underway, and then grew into a workshop where gymnastic equipment was made: l’universidad del amor, a mobile body-building club, accessible to one and all, and free of charge, came into being.

Using found materials—flotsam and jetsam, tins, tyres, bricks, composite materials—exercise benches, dumb-bells, and weights were all produced. This club took shape in various places and, first and foremost, during the Contemporary Art Fair in Barranquilla. On each occasion, visitors stopped, put on the club outfit and got down to exercising. The most rewarding factor was always people helping one another and finding the best exercises on that equipment conceived for functions which would, it so happens, be found at a later date. The last occasion, in the artist’s presence, took place in an open air garage, in the middle of the village hosting it, well removed from the art world! For a whole weekend, enigmas became objects of barter, and the garage became a living place; together, they created forms of love which they tried to share.

Kindliness. This is the appropriate word to use when you describe what fills the artist’s gaze. Especially when she works in a school setting, which is something she does regularly. Needless to say, the old generation sees the its structures being split when it looks at Generation Z, born on the cusp of the millennium. Anaïs Touchot, for her part, detects a great confusion there: why take your baccalaureat exams when you’re going to become a craftsman? Why undertake lengthy studies and become a polyglot when you’re forever being told that there’s no work anymore, and you’re going to be quickly replaced by robots? How are you going to have a life where a nice atmosphere rules even (and above all!) precisely where people are earning money?

Rather than passing judgement on the maturity of these young people and their capacity to concentrate, Anaïs Touchot decided to create a well-being center for them, “a space which they can appropriate for themselves, and which they are responsible for, in perfect autonomy.” Sculpture in the form of massage chairs, paintings borrowing foot reflexology diagrams, a target riddled with nails, voodoo-fashion, nicknamed “unemployment”… All so many ways of encouraging their imagination and the appropriation of their bodies. It is, incidentally, on the basis of hunches that the artist uses the latest neuro-scientific discoveries: rather than showing them kittens (which inevitably causes endorphin to be released), she paints the word, permitting college students to themselves come up with the form which satisfies them. Her latest installation is intended to be a “bridge between body and mind”. So is this flesh/mind reconciliation not the main challenge of the 21st century? The only possible way for a generation so connected to technology to re-connect itself to the body of the other… and thus to its aspirations?

Translated by Simon Pleasance

Exhibition view "Tomber sous le vent", Centre d'Art, Neuchâtel, Suisse.

Exhibition view "Tomber sous le vent", Centre d'Art, Neuchâtel, Suisse.

Exhibition view "Tomber sous le vent", Centre d'Art, Neuchâtel, Suisse.

Exhibition view "Il était une foi", Château de Kerjean, Saint-Vougay

Exhibition view "S'embarquer sans biscuit", Passerelle Centre d'art contemporain, Brest.

Exhibition view "la Universidad del Amor" main street, Puerto Colombia, Colombia.

Exhibition view "la Universidad del Amor" main street Puerto Colombia, Colombia.

Exhibition view "la Universidad del Amor" main street, Puerto Colombia, Colombia.

Exhibition view "la Universidad del Amor" main street, Puerto Colombia, Colombia.

Exhibition view : galerie pédagogique, Cité scolaire de l'Iroise, Brest.

Exhibition view : galerie pédagogique, Cité scolaire de l'Iroise, Brest.

Exhibition view : galerie pédagogique, Cité scolaire de l'Iroise, Brest.