Sopitive Painting

In 2021, the Documents d’Artistes Network partnered with AICA France and the Art Newspaper France for the program “Points of View,” launched by the DDA network with the goal of writing and publishing critical texts using the Documents d’Artistes resource website. The first text by one of our four laureates, Elora Weill-Engerer, is published here; it has also been published in The Art Newspaper France and on the AICA France website.

The term sopitive (from sopio, “asleep; calm”), used by Roland Barthes, describes the softening and soothing nature of certain mucosal, milky and creamy substances whose components only adhere imperfectly: in between soft and liquid, the sopitive is marked by its material and visual, as well as sensual, symbolic and social properties. Metonymically, the sopitive image is nebulous, vaporous, made of layers and enveloping films; visually, its range is whites and pastels. This image is based on a paradox: physically impeded or morally inhibited, the eye is drawn to, or seduced by the sopitive but does not possess it. Thus it attracts and lulls, like a cake covered in frosting, inciting a hubris of surplus, of unusual overflow or out-of-self. In its tactile aspects and opaline depths, the sopitive image literally awakens the appetite. But to go beyond the strictly artistic, the sopitive addresses the problematic of the visible and invisible, contemplating the relationship of art to the real. What lies beneath this burying, perhaps mistakenly perceived as protective? Is it not in coating the primary object that the artist connects it to desire and knowledge?

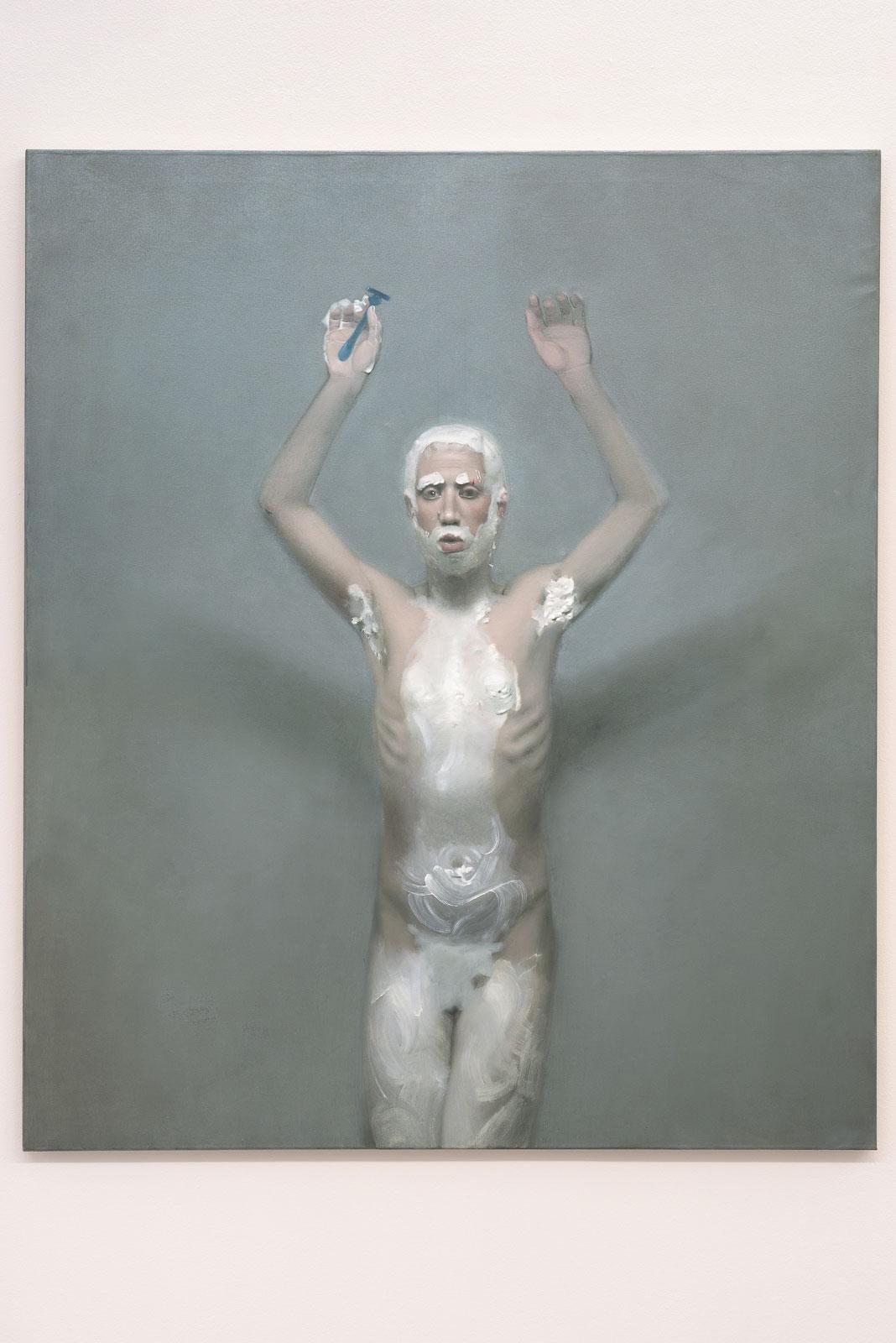

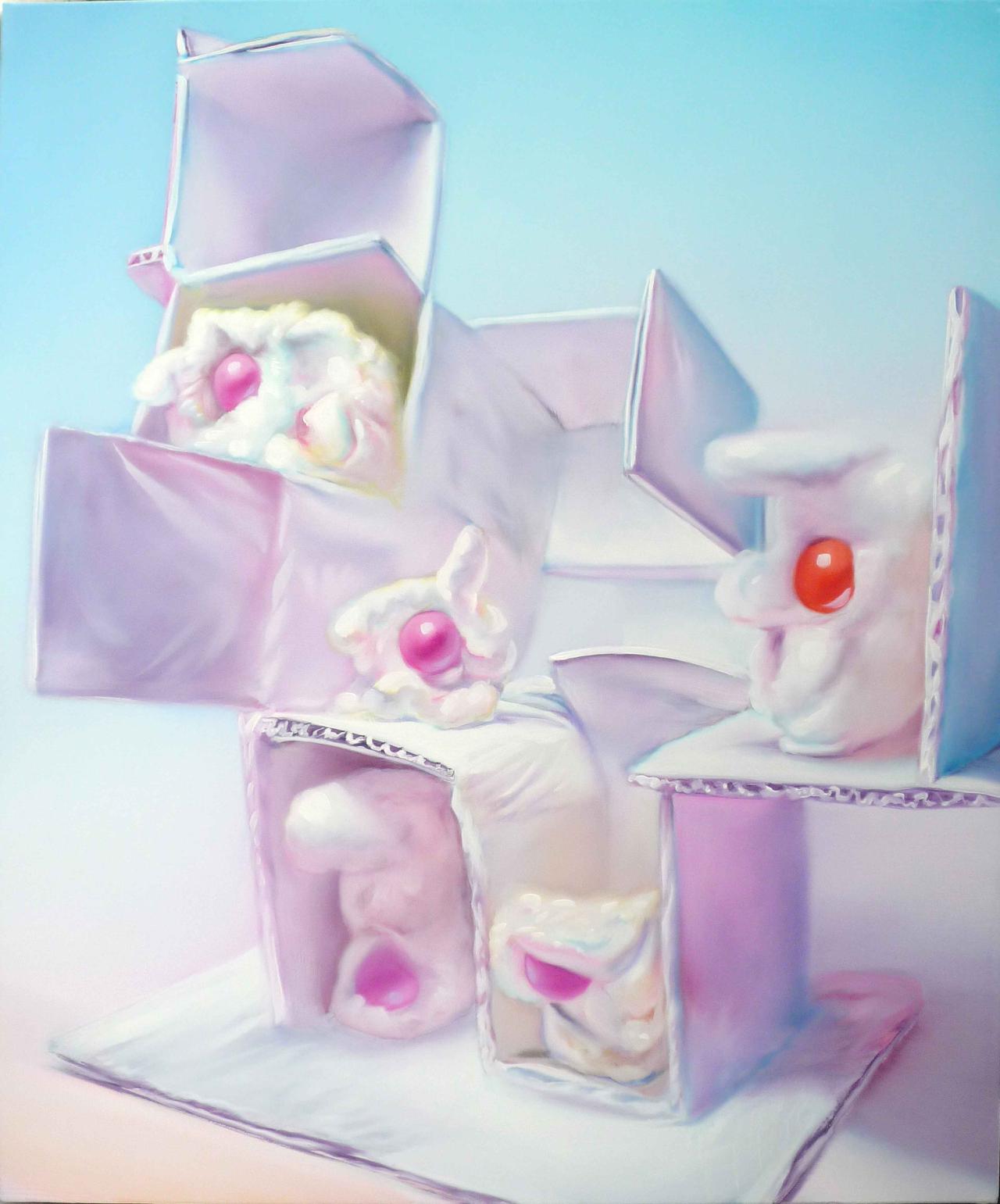

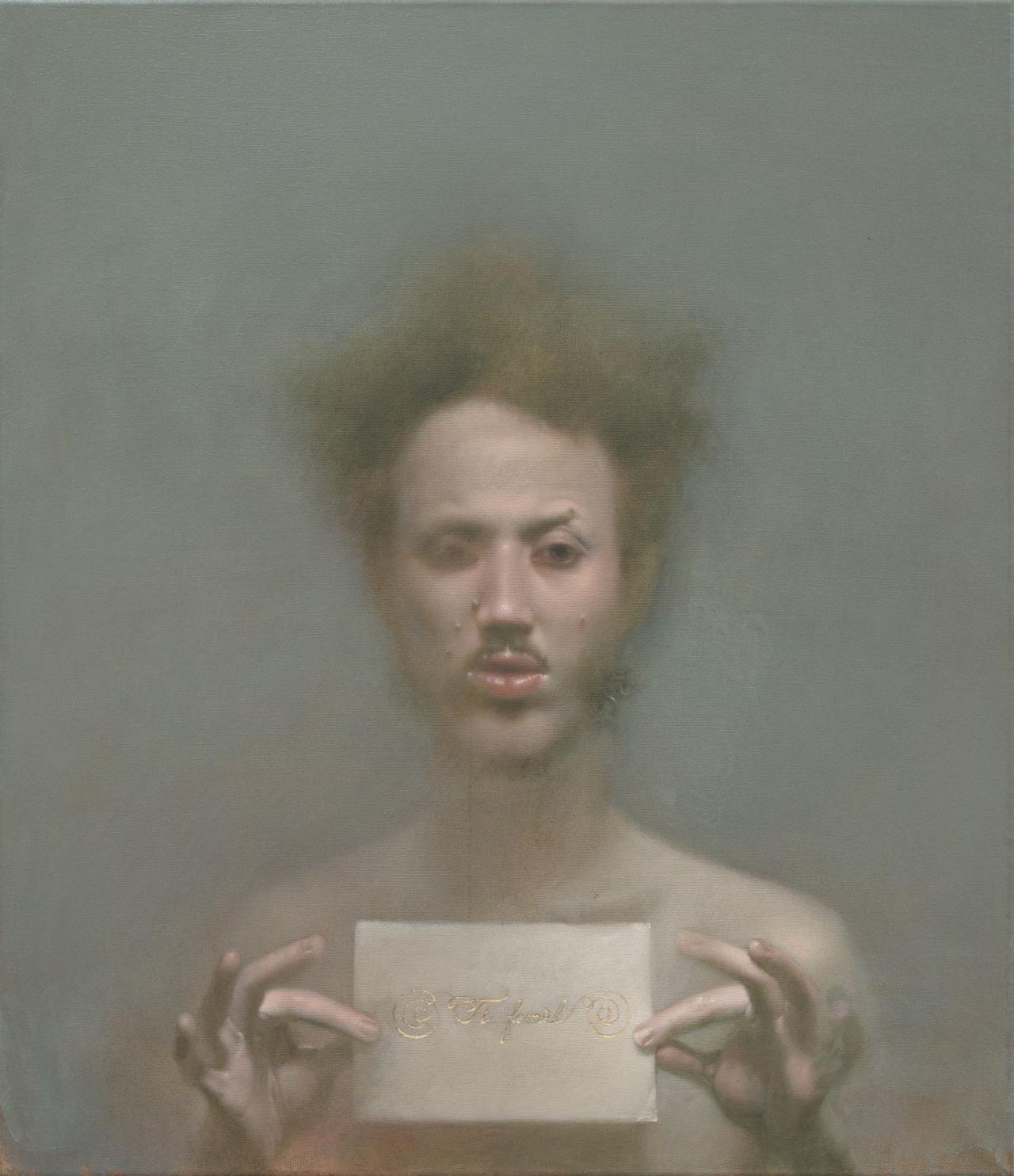

Studying a part of contemporary art in light of this notion makes it possible to connect different works of visual art through a vocabulary that might seem more appropriate to cooking: the soft, soothing, sweet or foamy. A pictorial approach to the sopitive can be quite productive in that painting itself can be understood as preparation, emulsion, plasticity and stratification. Hence the sopitive as the functioning of the image, but also as a metaphor for painting, with its coating, base, layers and glaze. Abel Techer and David Wolle are tied to this notion through different art practices, in literal and figurative ways. The paintings of these two artists have this in common: they summon a similar vision of the painted object, one in which the figure does not escape change. The sopitive is based on two themes, one of semi-liquid materials (fluids, viscosities, foams, creams), and another related to the transitory, fleeting, inconstant states of the social individual (Abel Techer) or the amorphous (David Wolle). On the subject of gestation or regeneration, the sopitive goes right along with the origin myth. In Techer as in Wolle, we find, in a singular manner, curios from childhood: porcelain rabbits, pompoms and trinkets, in the first case; marshmallows, salt dough, and sugar decorations in the second. For Techer, the accumulation of layers and glazes doubles that of the skin, which regrows symbolically with each molt of the subject. Cream and milk restore and fortify the physical attributes of the one who ingests them: “milk is cosmetic, it joins, covers, restores. Moreover, its purity, associated with the innocence of a child, is a token of strength, of a strength which is not revulsive, not congestive, but calm, white, lucid, the equal of reality” (Roland Barthes). Covered in shaving cream, shrouded in a milky haze, Techer’s gender fluid, hairless bodies dissolve in the surrounding space through a non-delineation of contours. Individuality encloses them no less in space than in time: the blurring recalls their mutating status, and the white, including classical symbols of virginal lactescence, returns them to a pre-natal state. The same principle of transformation can be found in Wolle’s paintings: out of a digital model or modeling clay, the artist builds a soft, polymorphous architecture with round, blunt lines that escape obvious function. Without any tangible background, the absence of scale confers them a gargantuan, autophagic dimension in which the sopitive body feeds on what it is made of. It gets glued like a fly to a trap. David Wolle’s creams droop, drip and turn to liquid from castles of almond paste collapsed under attack. The architectural and alimentary are interchangeable, Rococo tableware like old, formless pastries, the contents spilling the container. To use another formula by Barthes, painting has an “alimentary sensuality” that can be licked and savored, one that is both grotesque and gratifying. Morality repels it, the eye covets it. The sopitive coating is thus a guise of the pictorial medium itself, represented in this rococo kitchen whose base, or primary object, is sediment, buried under viscous layers with acid colors. At the same time, Wolle’s shapeless forms try to resemble something recognizable, like ghosts awkwardly posing as creatures of flesh and blood. Stimulating the eye with overkill as much as camouflage is the cry of the sopitive: the eye finds in the haptic, a term for the phenomenon of touch, a new surface charged with desire. In contrast to the optic, the haptic calls up a smooth space, nonstriated and without visual depth, “a space of affects more than one of properties” (Gilles Deleuze). Neither are there rough edges in the sopitive, which, in the words of moisturizer advertising, annihilates wrinkles and pain

Oil on canvas, 65 x 50 cm

Courtesy galerie Ceysson & Bénétière

Huile sur toile, 80 x 100 cm.

Copyright Jérome Michel, Courtesy Maëlle Galerie. © Adagp, Paris

Huile sur toile, 50 x 50 cm

Courtesy galerie Ceysson & Bénétière

Pastel sec sur papier, 35 x 40 cm.

Copyright Jérome Michel, Courtesy Maëlle Galerie. © Adagp, Paris

Huile sur toile, 35 x 48 cm.

Copyright Jérome Michel, Courtesy Maëlle Galerie. © Adagp, Paris

Pastel sec sur papier, 30 x 35 cm.

Copyright Jérome Michel, Courtesy Maëlle Galerie. © Adagp, Paris

Huile sur toile, 120 x 130 cm

Collection FRAC Languedoc-Roussillon, Montpellier

Oil on canvas, 120 x 140 cm

Copyright Jérome Michel, Courtesy Maëlle Galerie. © Adagp, Paris

Huile sur toile, 120 x 140 cm.

Copyright Jérome Michel, Courtesy Maëlle Galerie. © Adagp, Paris

Huile sur toile, 81 x 65 cm

Courtesy galerie Ceysson & Bénétière

Huile sur toile, 130 x 97 cm

Courtesy galerie Ceysson & Bénétière

Huile sur toile, 65 x 54 cm

Courtesy galerie Ceysson & Bénétière

Huile sur toile, 35 x 35 cm

Courtesy galerie Ceysson & Bénétière

Huile sur toile, 27 x 22 cm

Courtesy galerie Ceysson & Bénétière

Huile sur toile, 60 x 70 cm.

Copyright Jérome Michel, Courtesy Maëlle Galerie. © Adagp, Paris