Florent Meng

Beyond Platonic Armistices

The links between contemporary art and documentary photography trace a complex history throughout the 20th century, despite the fact that each one of the fields has dug itself in behind its specific features. To be sure, their distribution circuits and their production economies belong to parallel worlds, just as much as their creative strategies. But over and above this structural observation, the affinities we come across are based on shared ontological postures: a community of subjects, and often even one and the same critical ambition involving more or less tangible social transformation.

In the art world, the use of photos (press, utilitarian, vernacular…) with extremely varied projects produces eclectic forms; but whether it is a matter of criticizing the information system, analyzing image procedures, creating new narratives, or kindling a collective memory, practically all the processes try to introduce reality into art, and bring art closer to life.

Where the documentary photo is concerned, what is first and foremost involved is to stay aloof from photo-journalism in order to remove oneself from the raw event, from the image’s amazement-inducing effect, and act upon the resulting system of interpretation. How are we to display the complexity of political and social situations through imagery?

The criticisms levelled by this fringe of photographers to some extent link up with those posited by the art of the 1960s: does the exhibition as an institution make any sense? How are we to sidestep the heroicization of the author, call upon reflection, and organize a diversity of viewpoints for the image?

Several artists, among them François Hers, Gilles Saussier and Philippe Bazin, started out as photographers in the field before developing the subtle methods of the “critical documentary”, which re-incorporates the photo in broader areas of knowledge; and before them, Allan Sekula, an enlightened foe of the effects of globalization, was linking images to bodies of painting, writing, and film.

A thousand ways of creating boundaries

At the root of all these reflections, and over and above the perceptive mainsprings of the image, we find issues to do with society, which have been powerfully taken in charge by artists for the past two decades. Assuming an art exercised by the social fact, they multiply the number of viewpoints, staying well away from the claimed authenticity of the documentary. Nor do they underwrite the issues of medium analysis, or the ideas of photography as a visual art. In practicing immersion in the field, they round off their experience by consulting archives, scientific data, and surveys, and, above all, they straightforwardly practice overlaps between film, performance, science-fiction, literature and visual arts.

Among them, Florent Meng, an artist by training, tacks between numerous visual styles and forms ranging from image appropriation to the critical documentary. Attracted by border and divided areas: Lebanon, US-Mexico border, the West Bank…, he deals with the identity issue which is consubstantial with these parcellings, and cogently compares reality and fiction: Notes sur H2, a film which smacks of apocalypse, finds its source in the life of a deserted neighbourhood of the city of Hebron; Chroniques palestiniennes/Palestinian reports, whose title echoes the Chroniques martiennes, uses an ethnological pretext; the Préambule alinéa H/Preamble paragraph H photos and the film Parking speculate about the effects of multi-confessionalism in Lebanon.

These two works start out from the famous paragraph H in the Lebanese constitution, which provides for a staggered abolition, in stages, of state confessionalism, but has never been applied. The lives of the inhabitants are hampered by the invisible barriers which put a brake on amorous relationships between different religions. The major demonstrations of the 2010s in favour of a legalization of civil marriage have not culminated in the slightest reform. Florent Meng opts for an allusive approach to the subject: photos of peri-urban areas which are as vast as they are disaffected and act as a refuge for young lovers, dialogue with urban views, displaying impressive ‘wedplanners’ advertisements. With regard to marriage as an economic value, the artist reverts to the most intimate scale of this institution, the relation between two bodies, seen from afar. As a marker of the grip of power over the individual, the body undergoes the power which, as Foucault says, is not a thing, but “an action on actions, a conduct of conducts”.1This is an idea which seems to run through the whole of Florent Meng’s oeuvre; his work keeps an eye on the effects of these forces, and ends up, in the end of the day, on bodies.

In 2015, when, with two friends of Mexican origin, he came up with the idea for the film Dunes of Deletes, he discovered the issue of illegal migrations on the border between Mexico and the United States. Present himself at least twice a year in the field since then, he has created bonds with inhabitants and activities over a huge region that runs from California to Arizona.

This film was shot in the Mojave desert along the border, with these two immigrant characters. Their long walk in the Sonoran desert gradually sheds its reality and nudges the scenario towards fiction. The weariness of the bodies, the crushing immensity of the landscape, bolstered by literary and film references, make the viewer shift towards a mirage-like sensation--put at an accentuated distance by the artist, who introduces visual arrangements like mirrors and green backgrounds2 unfurled in the landscape, suggesting an adjournment, a duplication of the image, and an absence. The film’s principle—crossing the border—effectively leads to an outburst of reality when one of the participants, a ‘dreamer’,3 does not want to be part of the shoot any more, afraid of being arrested if he gets close to the border.

AZ/SN: geography, history and politics.

These movements between reality, artifice and fiction, which are highly mastered in Florent Meng’s movies, are present in a different way in his photographs, because they are mainly based on framing procedures and subject choices: sober shots, at times “chilled” in the studio, avoidance in the image of expected subjects (the wall, barbed wire, migrants) permitting the onlooker to work out a certain distancing; connecting images in sets which can be put together in different ways from one show to the next.

The large series of photographs titled AZ/SN4 which he produced in this zone is constructed on a dialectic which he makes his principal research issue: “How does a territory act on the ways communities behave, and how, in return, can attitudes and habits fashion the identity of a territory and a people?”

This series is organized in sub-sets which proceed from clue to symbol to narrative, involving, through these semantic styles, several systems for image reception. The first, titled Trails of Sasabe, came into being from the artist’s 1000-mile wanderings on both sides of the border. Sasabe, which is the last border village before the Mexican frontier, situated to the north of the Altar valley, has seen its economy grow thanks to passing migrants.5 This is a somewhat sinister detail, when we associate it with the deaths reported day-in day-out on the other side of the border, caused by climatic conditions. But the entire border ecosystem is based on double meanings and contradictions: the NAFTA free trade agreements (1994) resulted in the liberalization of the land market in Mexico and the eviction of thousands of small-time farmers and countryfolk, no longer able to subsist. These latter, and more generally the impoverished populations of Central America, often under the yoke of drug cartels, have immigrated on a massive scale to the USA, despite many a warning shot from the American government (the Obama and Trump administrations), which has introduced enforced deportation (shipping people back home) and heavy penalties. An ever-growing number of laws now tend to criminalize illegal immigration; but the American economy needs cheap labour on a daily basis, and this manpower is transported across the border from Mexico, from dawn to dusk…

It is in this climate of tension between arrangements favourable to the economy, and laws which are devastating for the populace, that survival is organized, involving a perforce illegal brand of immigration. In this part of the democratic world, as in many others, there has been a divorce between ethics and the law, which is spreading an invisible disaster upon human lives.

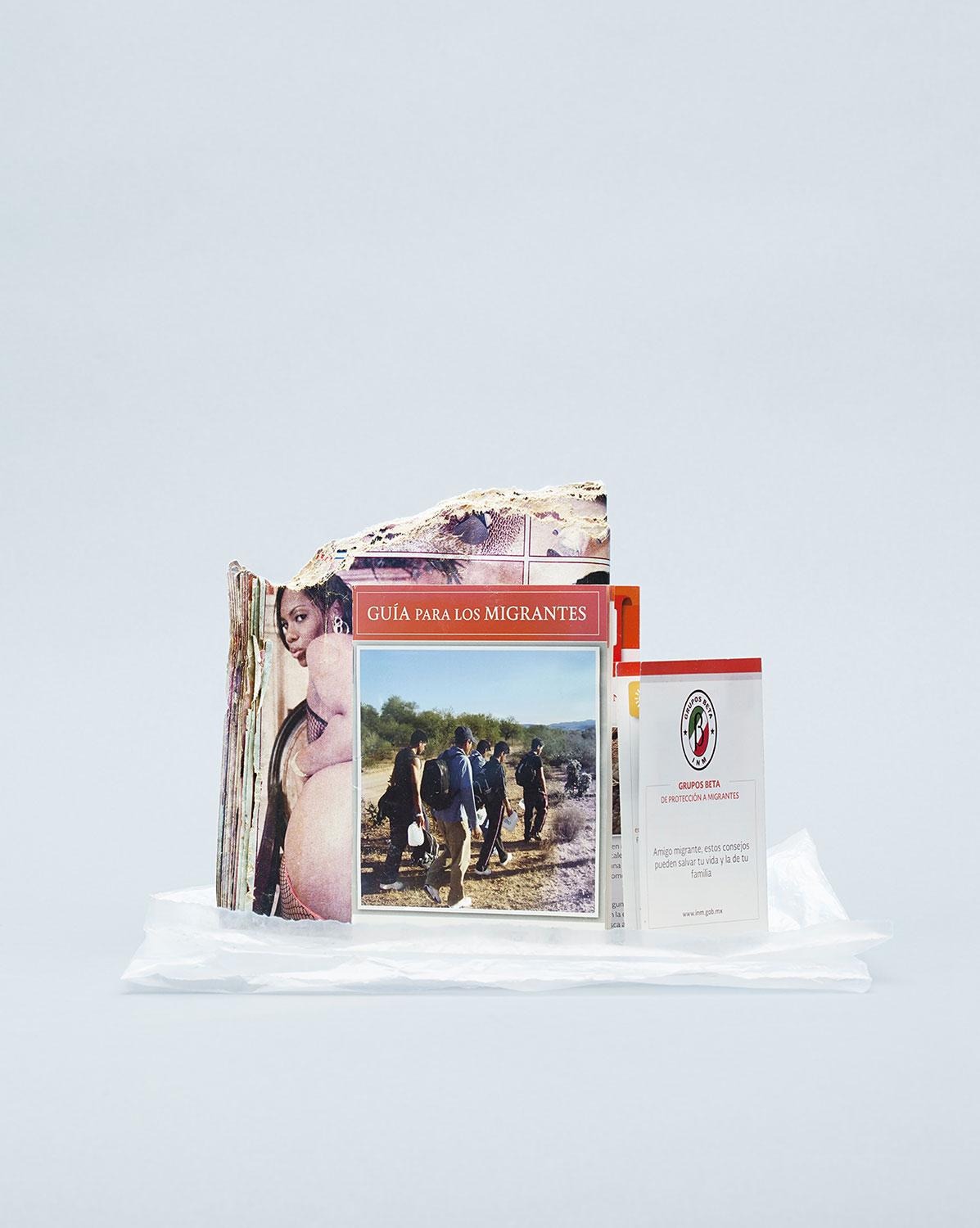

The chapter “Trails of Sasabe” alternates views of objects and landscapes, in an allegorical system which encompasses references to history as well as input to do with sampling: history, for those mustard plants which arrived here in the 16th century, sown by missionaries to stake out the settler’s trail, the image of the desert floor, somewhere between reconstruction and abstraction; it would be re-used in textile printing on amazing and inspired camouflage overalls, borrowing a use made by migrants with an appropriate distance. Enigmatic images, at first glance, which inform a basic part of Florent Meng’s work: the question of human displacement in arbitrarily drawn territories, the traces of which still get in the way of the course of human lives. Through a distancing effect, the harshly realistic photos of objects are taken in the studio, out of context: a water container complete with a handle made of worn rope, fragile soft shoes sewn in fabric, a booklet of tips for migrants published by the Mexican consulate, and survival items in a shop on the Mexican side of the border. A few hundred miles from the town of Sasabe, there is no border wall; the line is easy to cross, but lots of people die from dehydration well before they get to Tucson, in southern Arizona.

The set titled Ghost whisperers presents calculatedly ambivalent images, tacking between traces of power and traces of the body: technology and vertical steel structures to mark the crushing restriction—moral, physical and mental—which is concentrated around the border. Open sky radar for remote inspections (in the Sonora desert) is visually connected to an army terminal for urgent calls, a touching gesture of solidarity which complies with the ambient cynicism: out of several thousand calls, only two were answered, the artist specifies.

The photo of a crack in the ground retains something indeterminate. Resembling a scar, it seems to re-sew two areas of land together as much as it divides them. The artist associated it with the Japanese art of kintsugi: highlighting flaws in gold instead of concealing them. This is a photograph with a high symbolic coefficient, rubbing shoulders with photos of thoroughly tangible signs left by migrants, indicating an extreme degree of dereliction: a photo album, a dried plant on a grave, a makeshift shelter abandoned by miners, and re-used by migrants, miraculously flown over by a bird at the moment of the shutter click. A horde of small objects picked up in the desert by a member of No More Death are displayed on his dashboard like a handful of apotropaic talismans (warding off bad luck).

To the show Florent Meng adds sculptures which depict cows’ hooves carved in wood: this is a re-make of the clogs which migrants make and wear to disguise their footsteps. On the flat surface of the hoof, in contact with the foot, the artist’s present engravings: Chinga la migra-type slogans of anti-racist movements, archetypal views of the desert, ironic references to the police… Here the artist connects image and body, inviting us to project ourselves into the migrants’ steps, and into their invisibility. These “underfoot engravings” also have a matrix-like dimension: they are inked and printed under the foot and, by imagining that the free migrant abandons his clog, he would place an imprint on American soil… A way of pinpointing these destinies conditioned by clandestinity, forced to tack between resistance and illusion. Another photo shows a tribute-like work affixed to the border by Mexican artists. It is titled Paseo de Humanida. It could not be better put.

In The Crossers, the third AZ/SN set, Florent Meng draws the eye towards action in the field. Some of the images freeze on those coolly efficient inspection systems, invariably strikingly disproportionate, and unashamedly cruel: mobile radar surveillance systems, barbed-wire installations designed to slash people at child’s height on the border at Nogales, texts of laws criminalizing immigration.

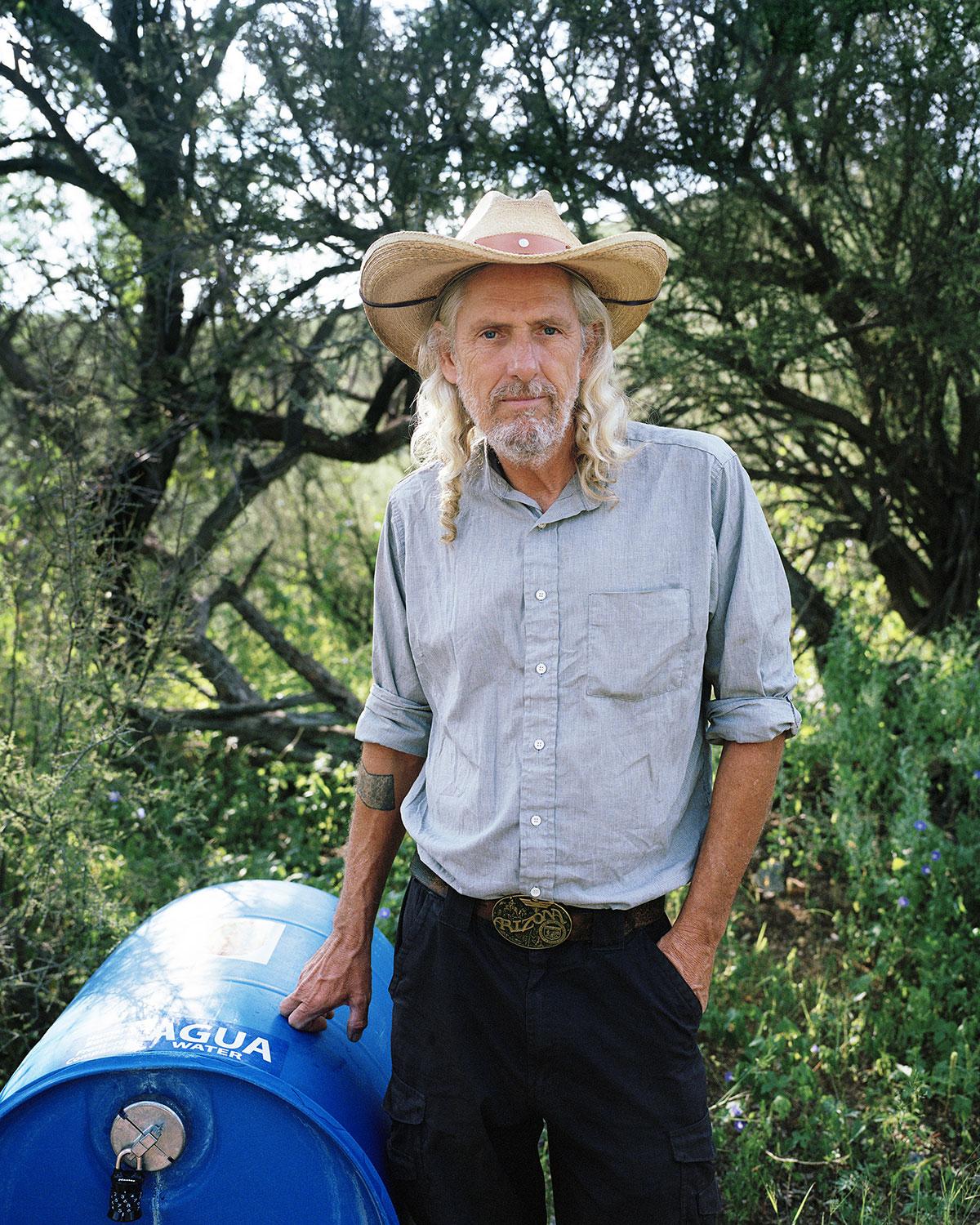

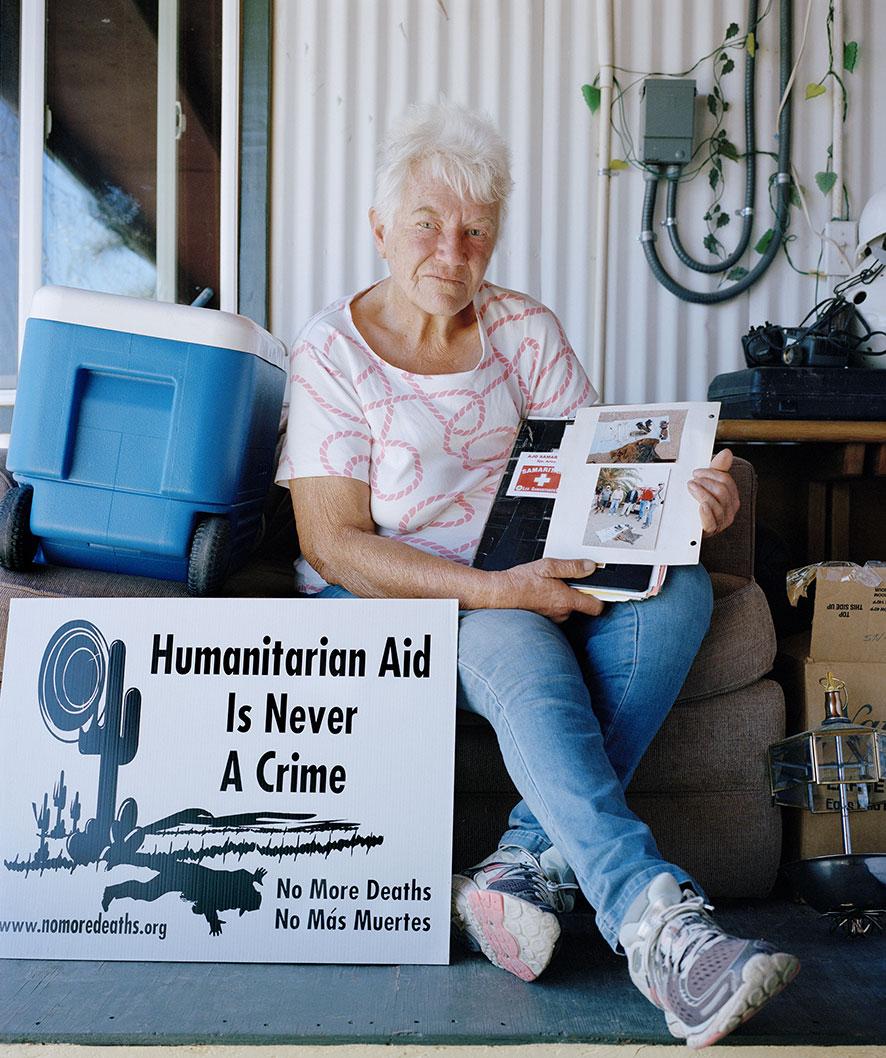

But they are countered and complemented by images of resistance in the form of documents (official protest by the town hall against this barbed wire, information documents for use by migrants), and views of resistance organization: permanent premises, militants in action handing out legal information to future migrants (American Civil Liberties Union—ACLU); water storage sites in the desert in critical places. Death is present in coded form—route maps, and their fearful ‘death maps’, which geo-locate dead bodies (Guia para los migrantes, Humane borders). Death is also indicated in real ways by burial places of differing forms (Hultville, Tucson). In a cemetery dedicated to migrants, a cross-installation ritual is observed (in particular) for media purposes by the Californian ONG ‘Border Angels’. Unidentified bodies are buried with the generic names Jane Doe and John Doe carved on a brick. Showing marked compliance with the documentary (clearly defined images, identifiable scenes), this sub-set includes portraits of activists in these NGOs, whom Florent Meng rubs shoulders with when he takes part with them in certain actions.

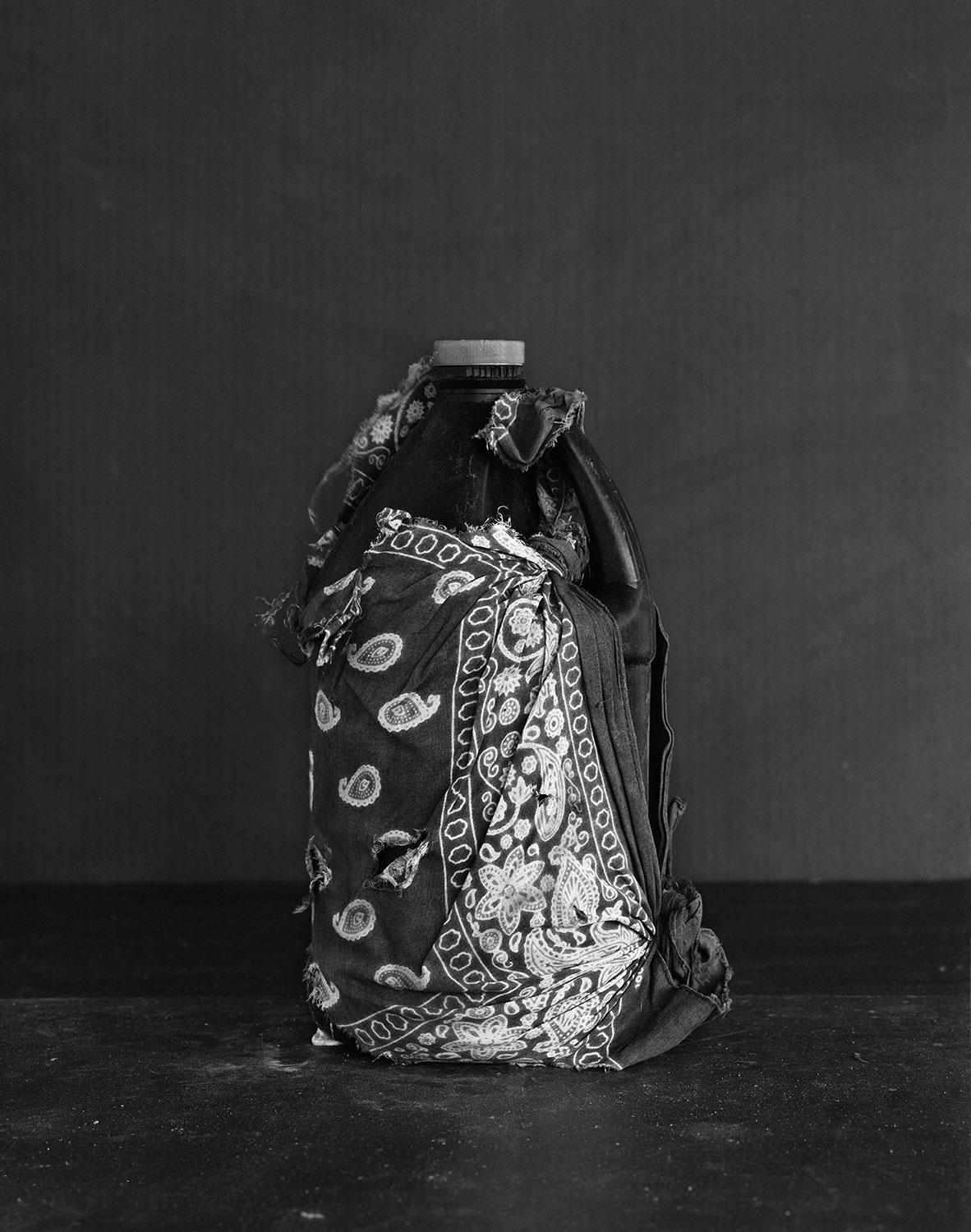

The starting point for the IV series is a collection held by Debbie McCullough, a member of the Samaritans, who has been criss-crossing the desert for the past twelve years to place water supplies in critical spots. The very idea of collecting things abandoned by dead people is problematic, especially in a private sphere which relieves it of its possible historical and political scope. Florent Meng photographs some of these things in his studio, in black and white: water containers wrapped in cloth.

Through its visual power, this series is impressive. Nothing is attempted here to dramatize things. The repetition of these cans draped in cloth, their sober lighting, and their tight framing tend rather to project us into the space of sculpture. But by this very frugality, receiving full force the part of history they are carrying, we can make out an army of resisters. Effectiveness of a photographic choice that thwarts easy answers, whose depth is freely assumed by the viewer.

The other part of the images are views of organ-pipe cacti, a protected species in Arizona, whose longevity suggests that they have grown successively first on one side of the border, then on the other, based on the adage of the Tohono O’odam Indian nation: “We didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us”,6 for whom arbitrarily altered borders have caused social catastrophes. As figures of a passive resistance, produced in black and white, the organ-pipe cacti are also depicted dead, lying on the ground, immense bodies with an almost mineral texture, receiving, like the water cans, a corporal projection on the part of the viewer, this body that the artist conjures up and senses in the border: “The images brought together form a cryptography, expressing, each in their own way, the fact that there is a complex relation between those who “are one with” and the desert, an abstract and absorbing landscape”.7

Polarized with regard to political situations where power weighs on freedoms and entails far-reaching social and individual consequences, Florent Meng has to dodge the risk of assigning roles: those who look at, and those who are looked at.

The iconic and visual media and styles at work in AZ/SN (photos, films, writings, sculptures) also trace moments of life, the mirroring of situations in which the artist is affected in a cognitive and bodily way. Some objects are obvious witnesses to this, like the camouflage overalls, their cloth printed with an image of the desert floor, presented empty in the show, and upright. Taking (or not taking) photos, and transforming them, comes afterwards, to approach the subject that runs through his oeuvre: the democratic illusion and the repressed content it produces.

Around an inner border, Europe-style

Borders and repressed contents are still in question with the national photographic commission “flux – a society in motion”,8awarded to Florent Meng in 2019, which led him to work on the Annemasse area, on the Franco-Swiss border. Two unequally wealthy nations on either side of a border… the scenario is familiar, and the history of the two countries has unfolded for centuries between customs treaties and controls. The photos in this series show a dual society made of rejection: unequal export rights, abolition of seasonal labour agreements, reducing workers’ rights to nil, absence of any European feeling (pinpointed by an official tract after the Maastricht treaty, displaying the flag of Savoy), and with the identitarian martingale never far away, promotion of a pseudo “Lemanic identity” by the “Mouvement citoyen genevois”, which is hostile to cross-border workers, and all manner of integration. Like a highly meaningful archive, a beer bottle from the 1920s containing visiting cards belonging to Italian, Swiss and French workers dispatches us into the between-the-wars years on the Franco-Swiss frontier. The search for employment, in its then archaic state, shows what it still is: a primitive workforce market in which the worker is both merchant and merchandise.

Florent Meng imposes the power of anxiety of the photograph, by promoting an historical depth located off-screen, which is confirmed in another photo: the façade of the Hotel Pax, in Annemasse, now abandoned, which has accommodated a large prison, and was also a Nazi SS interrogation centre in France.

The photographic methods applied by Florent Meng are numerous, and they are not all described here. Starting with his own words, which express his interest in forms of resistance to power, we find an initial basis of meaning.

It is important to note that the laconic quality of his images is not embarked upon by his immersion in the field, or by his occasional engagement. His relation to photography is even counter-balanced by this ethic. If he places himself as an actor rather than as an outside spectator, this is not in order to “touch” people with eloquent images. He seeks to grasp the power plays which condition events, and lend his images the depth of history and geopolitics. The echoes and rebounds in his series of images, and their presentation as variable installations, endow them with many different networks of meaning and interpretation.

This position, which is akin to the participatory observation of anthropologists, gives him the power to act on the world, by entering into a relation with it. One must agree to be affected in order, in return, to be able to achieve a conversion, which he, for his part, does in photographic writing. A form of “resonance”, as Hartmut Rosa9 has defined it, to confront a world which resists, and without any doubt, to encounter a response, each and every time.

By Françoise Lonardoni

Translated by Simon Pleasance

Notes :

The title of the text is taken from the Feuillets d’hypnos by René Char.

1. Matthieu Merlin : Foucault, le pouvoir et le problème du corps social - Idées économiques et sociales 2009/1 (N° 155), pages 51 to 59

2. The green background in video makes it possible to embed an image in another ground. The green screen used in the landscape of the film takes on a metaphorical value, indicating for the artist an image in the offing, which he associates with many other references.

3. They are called "dreamers" in reference to the "DREAM Act", the law regularizing children arriving very young in the United States, who have studied or enlisted in the army, but are threatened with being sent back home. This law has never been adopted.

4. Arizona/Sonora

5. In the early 1990s, 75 % of migrants crossed the border using the Tijuana-San Diego corridor, but tighter border controls there shifted crossing points towards Sonora - Altar, where a large number of deaths are recorded every day.

Jorge Durand, ‘La dynamique migratoire au Mexique’, Hommes & migrations – 2012.

6. This Indian nation lived in the vast area that extends from the south of the Sonora desert (Mexico) to central Arizona (USA). Since the mid-19th century, their territory has been divided into two by the Mexico-US border, which has been re-drawn several times. Today, they are no longer entitled to freely cross the border which splits their traditional lands.

7. Conversation with Florent Meng, June 2020.

8. Centre National des Arts Plastiques (Cnap) in partnership with the CRP/ Centre régional de la photographie Hauts-de-France et Diaphane, pôle photographique en Hauts-de-France.

9. Hartmut Rosa, Résonance, une sociologie de la relation au monde. La découverte, 2018

Video HD, 20’, Fr, Hebron Zone H2, 2013.

Video HD, 150’, Arabic with French subtitles, West Bank, 2014-2017.

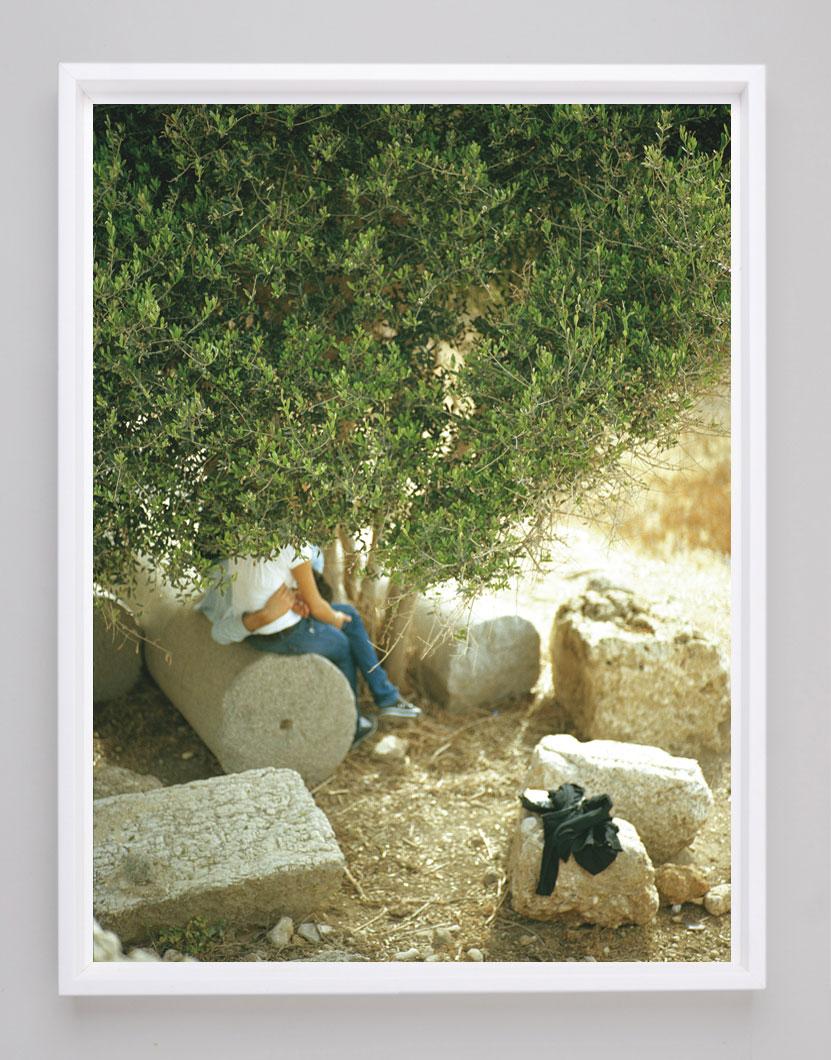

meeting places, archaeological site of Byblos, Jbeil, Lebanon 2010.

Digital print on aluminium, 80 x 52 cm.

Video HD, 44’, Fr / Eng / Span,

Mojave Reserve (U.S.A), Sonora Desert (Mex.), 2015-2016.

Exhibition view, Littéralement et dans tous les sens, Galerie Air de Paris, 2018.

Mustard plant, Tijuana (MX-BC).

Digital print on aluminium, 51 x 64 cm.

printed cotton overalls. In collaboration with Quynh Bui.

View of the exhibition Maybe a few minutes out of a million,

L'Assaut de la menuiserie, Saint-Etienne, November 2018.

Guide Grupos Beta. Digital print on aluminium, 51 x 64 cm.

Detail of Mural “Paseo de Humanidad“

realised by artists Alberto Morackis, Alfred Quiroz and Guadalupe Serrano, SN, MX, February 2018.

Digital print on aluminium, 51 x 64 cm.

Abandoned miner’s shelter serving as migrant hideouts, Ruby Rd near Arivaca, AZ, May 2019.

Digital print on aluminium, 80 x 64 cm.

Amulets, No More Death volunteer’s vehicle, Arivaca, AZ, February 2019.

Digital print on aluminium, 51 x 64 cm.

cherry wood clogs, laser engraving. In collaboration with Quynh Bui. View of the exhibition Maybe a few minutes out of a million, L'Assaut de la menuiserie, Saint-Etienne, November 2018.

Enrique Morones, Founder of Border Angels, paying homage to unknown migrants buried in Holtville Cemetery, Imperial Valley, CA, February 2018. Digital print on aluminium, 80 x 64 cm. View of the exhibition Maybe a few minutes out of a million, L'Assaut de la menuiserie, Saint-Etienne, November 2018.

Puente Human Right Movement Rally vs Patriot AZ movement,

Manicopa Sheriff ’s office, Phoenix, AZ. August 22, 2018.

Digital print on aluminium, 80 x 64 cm.

Joel Smith, Humane Borders Operation Manager, Arivaca, August 2018.

Digital print on aluminium, 51 x 64 cm.

Gayle Weyer’s, Ajo resident, holding a folder in which she collects photos of human remains discovered in Aqua Prieta area, Ajo, AZ, May, 2019.

Jug, Debby McCullough collection,

Digital print, 50 x 40 cm, 2019.

Saguaro Cactus, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument,

Digital print, 50 x 40 cm, 2019.