Chloé Robert

"Faced with a wild beast"1

Since the beginning of her practice as an artist, drawing has permeated Chloé Robert’s work. It infiltrates like a language, occupying all spaces and materials: first paper, then the walls, canvas, video, and more. Whether choosing the efficiency of black & white for works in Indian ink, or the freshness of vivid color compositions, her work is marked by a desire to get to the heart of things, not through visual sobriety as much as through a direct confrontation with a world of forms that stare defiantly at us, at humans, from within the circle of living beings. Her work advances from a fantasized wild state to possible crossings between humans and animals, pictorial chimeras reflecting the complexity of our relationship to life.

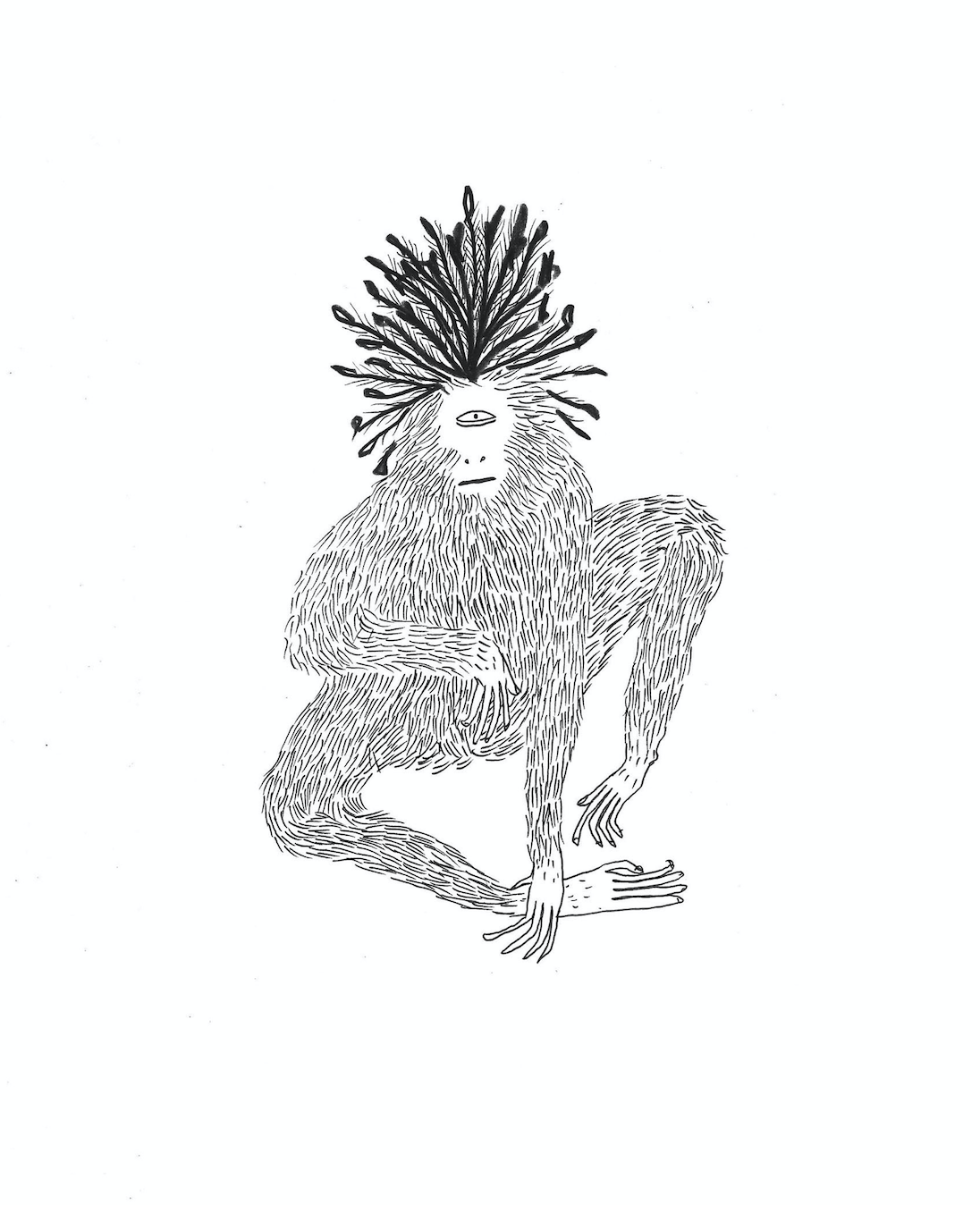

Robert has developed a practice of drawing following what she experiences of the world. Quite early on, while studying at École Nationale de Bourges, she portrayed the diversity of encounters, aspects of daily life and visual culture. Her sources of inspiration vary: an image from a film, an excerpt from a book or a melody is enough to spark the desire to leave a trace of this contact between souls on paper. Discovering lemurs while watching a documentary was a crucial moment. Upon seeing these little primates with big, arresting eyes, she began drawing portraits that stare back at us as we look at them. There’s nothing trivial about this as the artist’s intention is to confront us with the disappearance of animals via conquest of the land, revealing invisible communities. “How often have we seen nothing of the life in a given place?”, Baptiste Morizot asks in Manières d’être vivants. Probably every day 2.Robert seems to be making the same observation with her bestiary. Her gallery of animal portraits started with lemurs, souls condemned to wander between the worlds of the living and the dead. On one side the humans, on the other, everything else sacrificed on the altar of modernization. Robert brings this confrontation to light. She draws large numbers of portraits, paints lemurs, then wild animals, monkeys, birds, and whales with a black line against a white background, as if to overcome the blindness. Sometimes she places the animals in an “exotic” frame by adding lush floral detail. Oddly, a great number of the large animals making up her repertoire are not to be found on Réunion’s territory: “the island was uncultured, occupied only by ferocious animals, though I never saw one,” read the drawing on the wall at the exhibition Mutual Core 3. Thus, encounters between Robert and the animals take place through images. They form a world-scale ensemble, far from our experiences, at the center of myths about the wild. It’s a community we do not cohabit, one we keep at a distance through the illusion of proximity on screen.

Portraits with fluid contours, deployed on paper with a free gesture and mastered sensuality are generally large format. The artist glides her brush across the entire surface of the paper, almost spilling over, in a way announcing the work of mural: large compositions in black and white, or with a single color to make use of restraint and figure/ground contrast. Often, for exhibitions, she mixes paper and wall drawing, as in the project Sauvage at Galerie La Ligne, in 2014.

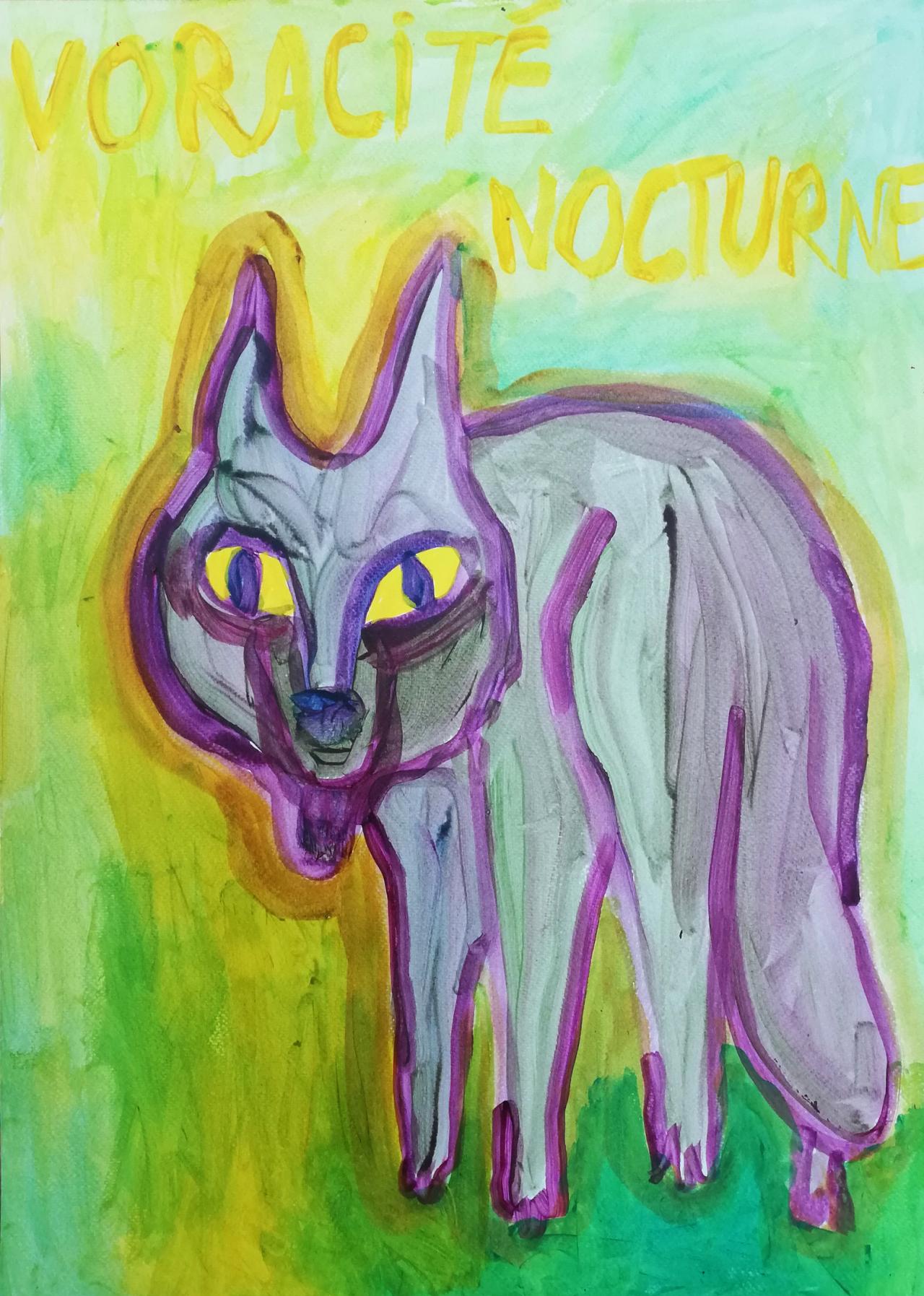

Then color comes in for the 2020 exhibition Les adieux de l’homme-huître (au petit occident), made in collaboration with Soleïman Badat, shown at TÉAT Champ Fleuri. Accompanying the wall decor of dispersed elements like animal heads and algae are a series of drawings using varied techniques and clay figurines. Stretched across the space of the wall, line becomes shapes in space, sharp silhouettes that might recall Matisse’s gouache cut-outs. And like Matisse,4 she draws (and writes) in color more than she paints. On a painting of a vixen, one reads: “Separated from the rest of the world.” Often words, hooks, slip into her work. They ring like sad observations, words we’re thinking rather than uttering, or cries of despair. These sounds are often muted, inaudible. “Human out” is the title of another drawing from 2015. When will the beasts rise up?

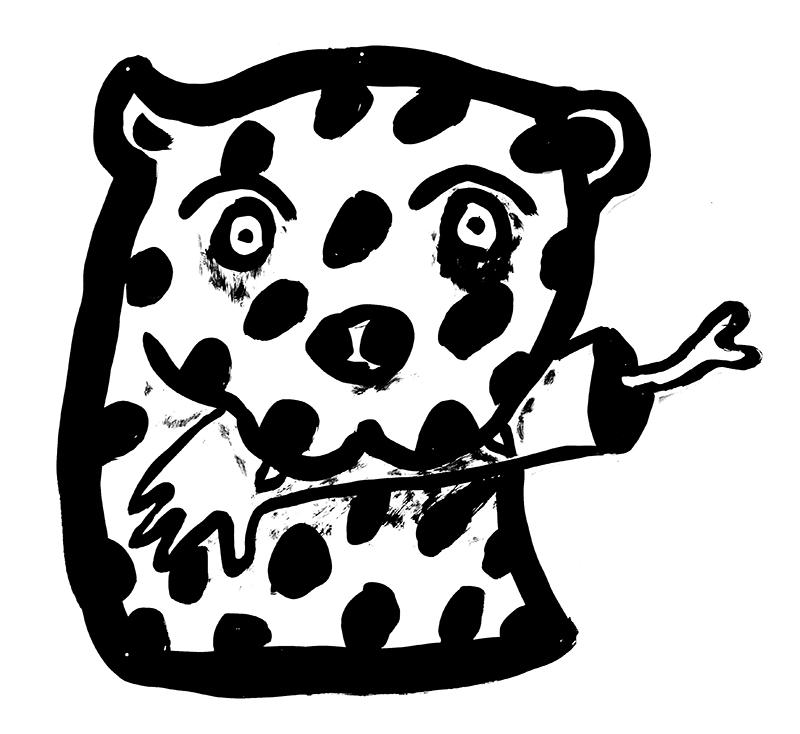

Co-creations by the duo Robert/Badat are numerous, as the collaboration began at a residency with Re-Creative Space 1905, in Shenyang, China in 2015, and continues periodically. At the beginning, a new artistic universe was born, mixing two worlds of form. It featured characters dressed as animals. Wearing masks and costumes, the figures play on ambiguity and mixed references evoking as much executions carried out by the Islamic State as elements of pagan animist culture5. In dressing up, wearing masks, and turning into beasts, the animality of the human is always in the background. Unsurprisingly, in her studio at Lerka in Saint-Denis, we find costumes and heads of animals worn, above all, “for acting,” as these accessories were created for filmed performances.

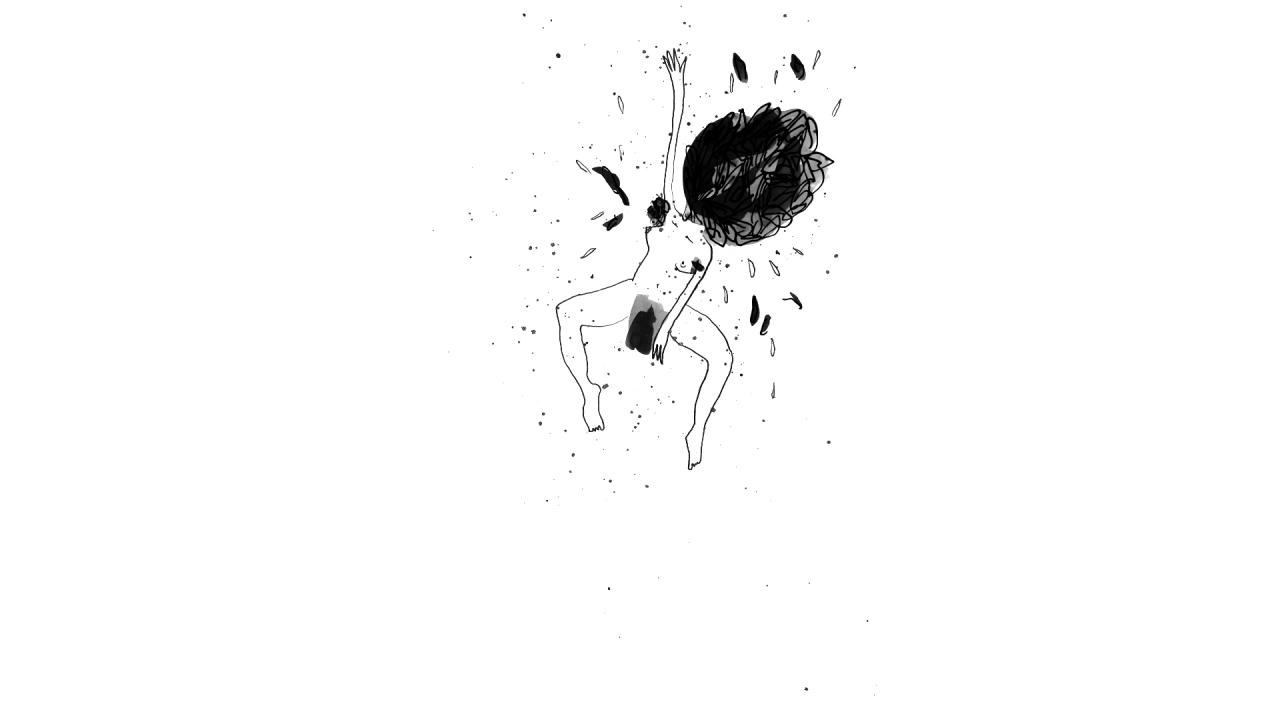

Robert’s work always evokes our common origins with the animal and botanical world (Femme buisson [“bush woman”], 2014) by decompartmentalizing categories within living things. We are a part of the Maillon ininterrompu de la grande chaîne de la nature 6 (“great unbroken chain of nature”), a circle dance re-performing, ridiculously and randomly, Darwin’s evolutionary narrative. The video from 2018 presents a series of charcoal sketches erased by the artist immediately after the photograph. The result is frame-by-frame animation expressing the drawing in its purest form. This hymn to the circle of life is also found (in a grimmer vein) in the project Danser pour les os et chanter pour la chair (dancing for the bones and singing for the flesh), shown at the lazaretto in La Grande Chaloupe, which was a quarantine station during the period of indentured servitude 7, now a heritage site managed by the region (of La Possession). In the ruins of this building, the artist’s large, suspended drawings on textile seem to float and find an echo chamber. The black skulls and skeletons, painted on fabric with floral or child-like motifs, resonate with the past of this site, evoking incarnated being, the spirit of flesh and bone, and descent.

Better understood as ritual, in terms of languages and practices that are not separate from life, Robert’s important body of work expresses life in all its dimensions, not without humor. Her work might, in this way, be qualified as “primitive,” less for its attraction to raw expression or its wild iconographic world, as for the cosmic energy running through it, returning drawing to the wall in an elementary, magical gesture of bringing two worlds into contact.

Written by Diana Madeleine

Translated from french by Elaine Krikorian

Notes :

1 The title of a publication by Zoëlle Zask, Face à une bête sauvage, Paris, Carnets parallèles, 2021.

2 Baptiste Morizot, Manières d’être vivants, enquêtes sur la vie à travers nous, Arles, Actes sud, 2020, p.15.

3 Exhibition at FRAC Réunion shown between November 2021 and March 2022 at the Artothèque Réunion, curated by Julie Crenn.

4 Also included among Robert’s favorite artists are contemporaries such as Charles Fréger, Karry Jameson, Solange Pessoa, Françoise Petrovitch and Théophile Perris.

5 Article published on the site Teat.re [Une exposition Intense et Fruitée selon Chloé Robert et Soleïman Badat !

6 [The work was acquired by Frac Réunion in 2022.

7 Indentured servitude replaced slavery in the colonies after its abolition in 1848. The system, which was implemented early on in La Réunion, engaged thousands of people from Africa, Madagascar, India, and China to work on contract in a colonialist context.

Acrylic on paper, 55 x 102 cm.

© Adagp, Paris, 2022.

Acrylic on paper, 74 x 104cm

© Adagp, Paris, 2022.

Acrylic on paper, 52 x 62,3cm

© Adagp, Paris, 2022.

Ink and grease pencil on paper, 21 x 28cm.

© Adagp, Paris, 2022.

Acrylic on paper, 55 x 102cm.

© Adagp, Paris, 2022.

Ink on paper 50 x 65cm.

© Adagp, Paris, 2022.

Wall painting, 3 x 2m.

Saint-Denis, La Réunion.

© Adagp, Paris, 2022.

exhibition view Mutual Core,

FRAC Réunion, Artothèque Réunion, 2021-2022

photo: Jacques Kuyten

exhibition view Sauvage

Galerie La Ligne, Saint-Denis, 2014.

exhibition view Les Adieux de l’Homme-Huître (au petit-occident),

with Soleïman Badat, TÉAT Champ Fleuri, Saint-Denis, La Réunion, 2020.

exhibition view Les Adieux de l’Homme-Huître (au petit-occident),

with Soleïman Badat, TÉAT Champ Fleuri, Saint-Denis, La Réunion, 2020.

Acrylic on paper, 42 x 50cm

© Adagp, Paris, 2022.

With Soleïman Badat. Mixed media on paper, 130 x 170cm.

© Adagp, Paris, 2022.

La femme buisson, 2014.

Animation, 25 s.

© Adagp, Paris, 2022.

Video, frame-by-frame charcoal animation, 1 min 4 s.

© Adagp, Paris, 2022.