Alice Aucuit

"Look inside the workshop of the alchemist:

When he extracts the spirit and salt of the plants,

He reduces everything to ashes, washes it, and

From this death brings back to life a perfect creation.

The exemplary secret of the enclosed ideasRevives in the tomb both lilies and roses,

Roots and branches, stems, leaves, and flowers

That dazzle our eyes with their vivid colors,

Their father is fire, their mother ashes.

Their resurrection should teach the fearful

That those burned, their ashes scattered to the winds,

Arise more vital, more beautiful than before.

Agrippa d’Aubigné, Les Tragiques, Book VII"

(Aubigné, Agrippa d’, and Valerie Worth-Stylianou. Agrippa d’Aubigné’s Les Tragiques / Translated, Annotated and with an Introduction by Valerie Worth-Stylianou. Tempe, Arizona: Arizona Center for Medieval & Renaissance Studies, 2020.)

Fire and Ashes

It might have been the residue of her past works, inhabiting as much as haunting her studio cabin, open to the wind; or the Bones (Os), Chimeras (Chimères) and other creatures that feed our imaginations like our nightmares, echoes of lullabies calling out from childhood; this cabinet of curiosities, with specimens multiplying like spores from the workbench to the floor, behind glass and on shelves; protuberances, detached limbs, bodies in substance, some revealing themselves briefly out of a loose wrapping—it could have been this…but what haunts me still is Alice Aucuit’s garden.

Alice Aucuit lives and works in Ligne Paradis. This is no fairytale. The small village to the south of the island of Réunion, in the commune of Saint Pierre, at an altitude of 100 meters, is surrounded by fields of sugarcane. The vegetation is lush, and the haven created by the artist is no exception. Yet in Aucuit’s garden, Eden and the underworld meet.

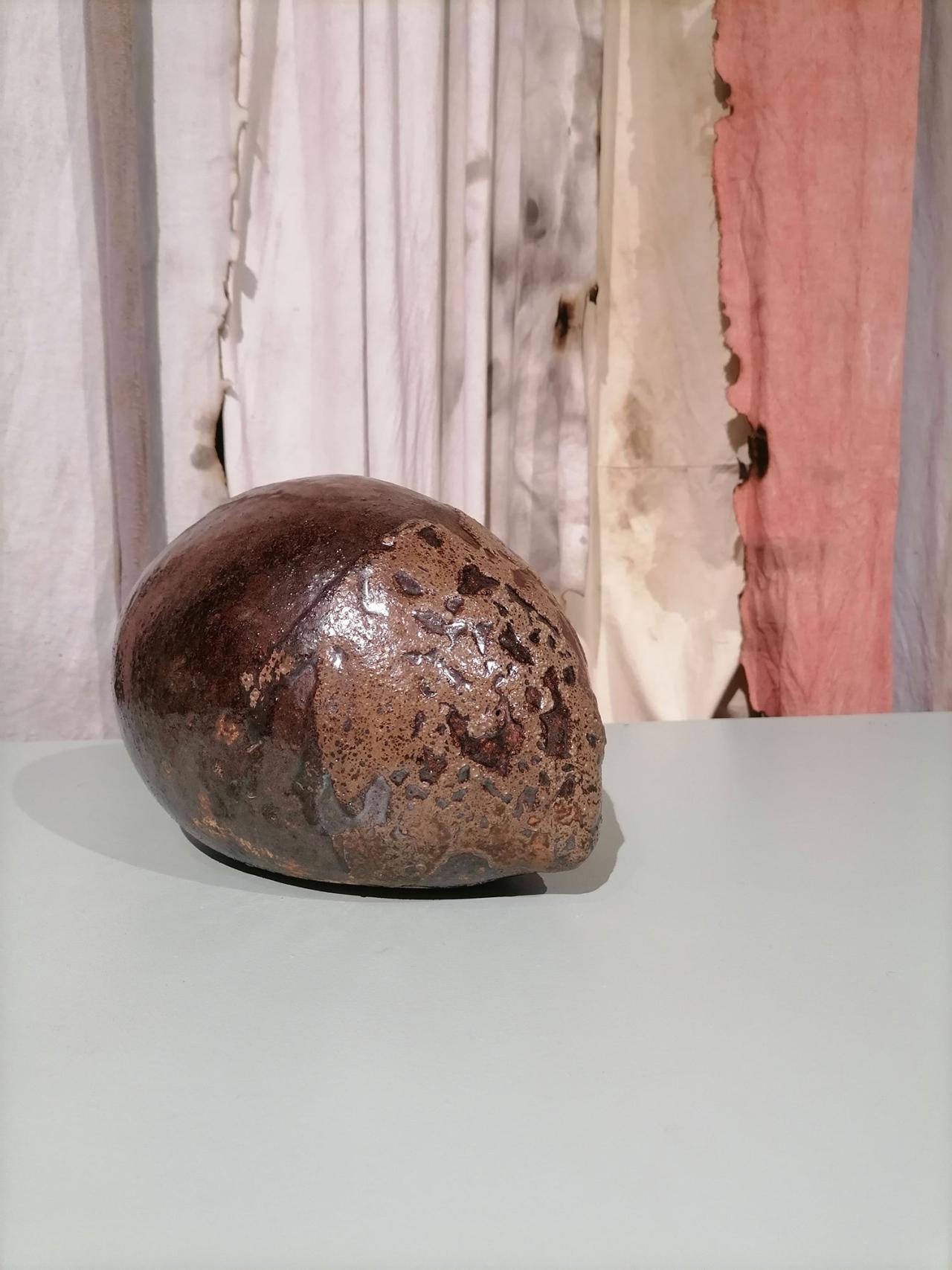

Lychee trees, dense with leaves, droop under the weight of their purple globes 1. Beneath their rough peel, a sweet, succulent flesh, with a rose-like fragrance, reveals oblong seeds. The gnarled trunks of tamarinds are set off by glistening green leaves and lavish flowers, orange-yellow with blood-red veins. Their tan pods, filled with a tart paste, conceal up to four little jewels. Fruit dangles within the evergreen foliage of the mango tree, crush a leaf to release an odor of turpentine. Those sweet, slightly acidic little fruits of the guava tree? A pain to some, a joy to others. Then to the bois noir, with its upright posture, gray bark, and flat, elongate seeds. The pepper tree with thousands of little beads, turning red in clusters, shaded by princess palms, giants with imposing canopies. Grasses make their way through volcanic soil littered with the windblown bagasse of sugar cane.

The garden is a living entity. From cool southern winter to muggy, boiling December, it beats in rhythm with the seasons. But the flamboyant vegetation shares quarters with all that will make it disappear tomorrow. Plumes of smoke rise through the air, a fire is lit in a metal container. The earth bears the marks of past fires, gone cold, or maybe still a little warm? The present one is white-hot, and the artist engages. She’s at work. From a rigorous selection of the skins, bark, leaves, pods and peels of occurring species, the vegetation begins its irreversible transmutation. Licked by flames, these multi-cellular organisms who, thanks to photosynthesis, can transform mineral matter from the environment into organic matter of their own, are swiftly shrunk to ashes to become mineral in turn. Alice Aucuit, keen on ancestral knowledge and trained in traditional as well as modern ceramic method, is conducting a territorialized study of vegetable ash. Starting from waste material (pruning waste, grapevine sarments, mowed hay, marsh plants, rice straw, coffee chaff, cut flowers), she draws on work carried out by the Bureau de Recherches Géologiques et Minières (French geological survey) on the soil and deposits of Réunion. The plant’s organic makeup, where it grows, the season and item harvested will determine the composition of the ash, then the characteristics of the glaze to be forged at high temperatures. Ash glazes, which appeared in China during the Zhou dynasty (-1100), were used to waterproof pottery. Today, they offer the artist a range of possibilities, both conceptual and visual, for realizing pieces.

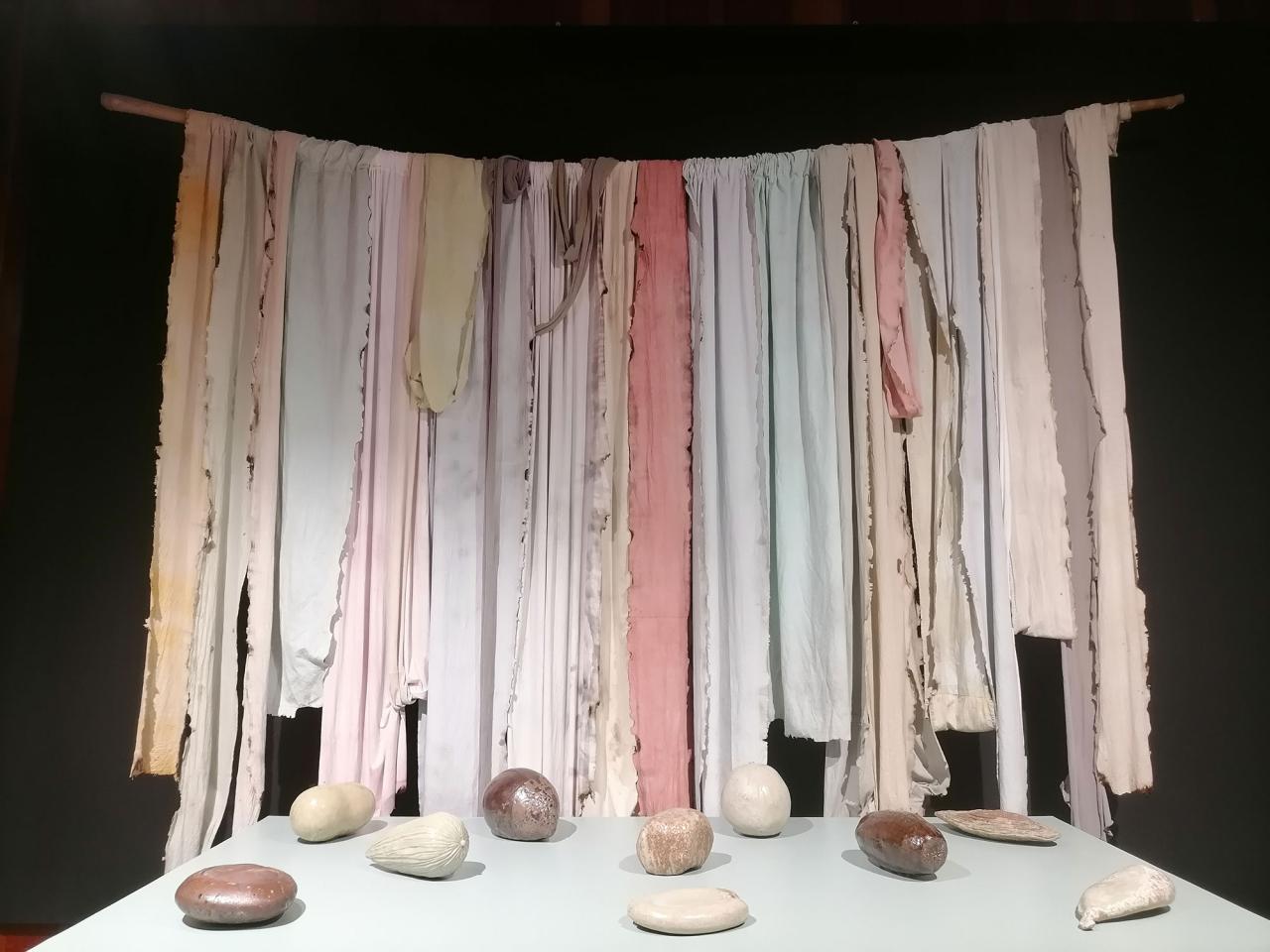

“It is in the molding of primordial mud that Genesis grounds its conviction. In sum, the true sculptor feels, as it were, tacitly, soft matter’s yearning to be molded, its desire to be born into form. Fire, life, breath lie latent in a lump of cold, thick, lifeless clay” 2. A few words by Gaston Bachelard place us instantly in the fingers of Alice Aucuit. She works as one with her material, speaking and listening to it, giving it form with deep respect. Wait, and with time a design comes into outline. Presently, a series of ceramic seeds are being created. They’ve increased in size. The seeds are the same species as those in the garden. They’ll soon be glazed with the same ashes that gave them life.

The work in progress echoes Le Cordon des Graines, created a few years earlier. The installation evokes the Roman myth of the Three Fates, deities who are the masters of human destiny, of birth and death. Some fifteen seeds made from Saint Amand clay, out of which a white glaze emerged, alluding as much to seminal fluid as breast milk, are displayed on traditional wooden machines used for weaving linen. Like Ariadne’s thread, the exhibition provides a metaphor on the possible paths of a life, between human construction and natural element, between direction and contingency.

In Aucuit’s practice, cycles take precedence. Cycles that echo sites inhabited by humans, by History and stories, our tangible and intangible shared heritage. And life cycles: birth, development, procreation, old age, death… reincarnation.Which soul, which vital substance, which individual conscience, energy and spirit appears? How is presence created from absence? Which memory should remain?

A muted pulse gives her work rhythm. In each project, a kèr (“heart” in Créole) takes form out of the surplus material removed during hollowing, at the precise moment when the clay has the consistency called “leather.” These vital organs slip into the kiln to be fixed by the fire in eternity. They’re then adorned in finery, the result of the artist’s inquiry into ashes to obtain endemic glazes, to be used wisely in later works. Perhaps one day she’ll also fulfill the (dis)honorable desire of incorporating ashes from cremation into her work, as “introducing ashes to a glaze adds life’s complexity to an inquiry” 3.

This text is a result of a meeting between the author and the artist in her studio at Ligne Paradis on Monday, August 23, 2021, as part of a Meet Up organized by Documents d’Artistes La Réunion.

1 Ref. “these vines which droop under the weight of their purple globes”, tr. Benet, Theresa Frances, Benét, William Rose, The East I Know, Paul Claudel, Yale University Press, 1914

2 tr. Haltman, Kenneth, Earth and Reveries of the Will, Gaston Bachelard, Dallas Institute Publications, 1943

3 Alice Aucuit

Translated by Elaine Krikorian.