Adrien Vescovi

“A few months ago, for example”, wrote Yves Klein in 1961 in his Manifeste de l’hôtel Chelsea [Chelsea Hotel Manifesto], “I felt an urgent need to record signs of atmospheric behaviour by receiving on a canvas the instant traces of spring showers, southerly winds, and flashes of lightning. (Need I explain that this latter attempt ended in a catastrophe?) For example, a journey from Paris to Nice would have been a waste of time if I hadn’t made the most of it to make a recording of wind. I placed a canvas, freshly coated with paint, on the roof of my white Citroën. And while I hurtled along the main road at 100 kph, the heat, the cold, the light, the wind and the rain acted in such a way that my canvas became prematurely aged”. “After all”, he concluded, “my aim is to extract and obtain the trace of the immediate in natural objects, whatever the influence, whether the circumstances are human, animal, vegetal or atmospheric.” As I travelled early in the summer of 2019 from Marseille to Nice to go to the opening of the Adrien Vescovi exhibition at the Galerie des Ponchettes, I thought of the trips this latter has regularly made with his canvases all rolled up between Paris and Savoy, then between Paris and Marseille, and I also thought of his large canvases currently placed facing the sea on the Promenade des Anglais, exposed to the wind and the sun for several months, and of Adrien’s words describing how the function of his paintings is to “record the landscape”. Adrien Vescovi’s painting is in fact an odd concoction. As a painter who uses neither rollers nor brushes, he cooks his canvases in infusion tanks for plants which he has initially collected in the mountain pastures of Savoy, before hanging them in wind and inclement weather. “Thinking of doing this like the confluence of forces and matter, and no longer laterally, like the transposition of an image onto an object, is tantamount to designing the generation of form, or morphogenesis, like a process”, writes the anthropologist Tim Ingold. “This makes it possible to reduce the distinction that can be made between organism and artefact”.1 Vescovi’s paintings, which, in a technical sense, are more hangings than paintings, are thus the product of different atmospheric forces which are part and parcel of the process set up by the artist. A process where the canvas “loads” the landscape, or rather becomes loaded with the landscape in which it is incorporated, in a time-frame that partly sidesteps that of “making” (faire) and shares it with a “laisser faire”. So one thinks of the artist Vivian Suter who, after a storm that had caused havoc in his studio in the Guatemala jungle, and lashed the canvases being stored there with rain, earth, and leaves, subsequently decided to leave his canvases in the open air, and to use, for painting, what the landscape put at his disposal in terms of juices of grasses, flowers and plants. Including hazard rather than fighting against it or protecting oneself from it. The plant infusions in which Vescovi’s canvases are steeped and boiled are a developing tank, not in the darkness of a photographic laboratory, but outside, where the canvases are quite literally exposed, not to say over-exposed, to the light which will speed up what they will reveal. Exposure to sunlight. By an association of ideas, I am thinking of the solar exposure of pieces of fabric folded by Katinka Bock, which she leaves exposed to sunlight on the roofs of museums where she is showing her work. Processes which do not minimize the artist’s own hand, as I wrote in an essay about Bock’s work,2 but include forms in time-frames which elude her, re-balancing forces between those of the human and the atmospheric.

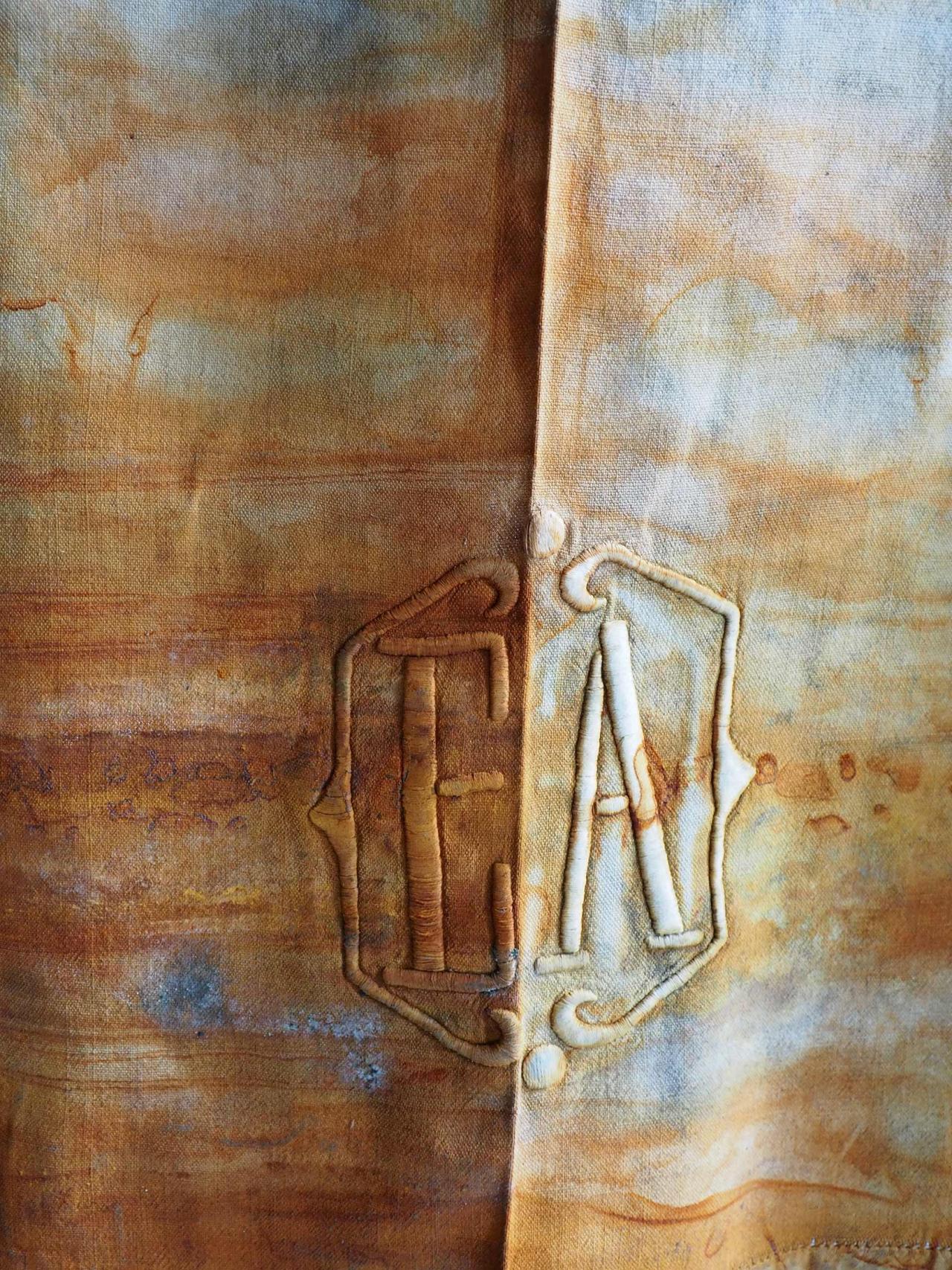

The notions of revelation and unveiling involve a materialist phenomenology with an unexpected form of spiritualism. Adrien Vescovi’s manner of developing his canvases, sewn in such a way as to form large colourful areas, either suspended or at times overlaid on each other, creates a strangely hieratic arrangement. Is this due to the fact that in addition to cotton cloth, he also uses as a surface embroidered and watermarked bed sheets, laundry items from another era conjuring up pieces of chasubles? In the Galerie des Ponchettes, arrayed as in a nave in wide bolts of free-hanging fabric among which the public moves about, while jars filled with coloured infusions on the floor go beyond ropes running along the walls, there is an impression of a ritual not to say liturgical system, but one which has nothing confessional about it. One thinks more of Helio Oiticica’s Parangolés on the beaches of Rio de Janeiro, or Franz Erhard Walther’s mural formations of coloured fabric which Vescovi regularly came across during his visits to the Mamco while he was a student. So many ways making painting referential, and connecting in a secondary way the living body, in motion, with colour, and producing something unfolded, an extension of the frontal relation to the picture, so as to produce a more immersive environment in the coloured surface, which is asserted by Vescovi’s installation at the Palais de Tokyo, where the assemblage of cloths more than five metres in height, suspended, forms a huge tent that you can walk through. This sort of shelter undoes the sensation of monumentality and, as for Walther’s works, which one critic compared to “sleeping giants”, we will endow their gigantism and the silence that this gives rise to with a metaphysical and meditative propensity rather than a form of domination creating the shock. The fold of the canvas, creating a shelter, proposes an immersion, an absorption, which thwarts any kind of aggressiveness from the monumentality.

Colour in Vescovi’s work is impure, neither bright nor clean. Those words are nevertheless probably an assertion calling for nuance and revision, because Vescovi’s last work at the Palais de Tokyo displays more dazzling colours than previously, which strangely evoke the colours of layered landscapes in Georgia O’Keeffe’s pictures: colours of skies, deserts and flowers, in layers more cut up than ordinarily. In any event, the shades of colours, due to the experimental aspect of Vescovi’s processes, are generally leached, marked and streaked in such a way as to never be presented as abstractions. They include the canvases in a time-frame, and thenceforth refer to the human factor, to its impurity, its finiteness and its vulnerability.

The same goes for the canvases which Adien Vescovi presents rolled around steel bars whose rust soon penetrates and invades the cloth. The reference to an ancient manuscript is not easy to dodge, but it is above all the invisible process of oxidization, imperceptibly extended, that interests Vescovi. When, close to the Cyclop in the Milly forest neat Fontainebleau, he arranges white cotton canvases on the ground, on steel rails, and kept in place by logs and iron bars, swiftly swollen by water and covered with leaves, what is involved is obtaining the trace of immediacy, the corruption of the immaculate canvases by time and weather, another arrangement somewhere between monumentality and vulnerability.

François Piron, October 2019

Translated by Simon Pleasance & Fronza Woods

Notes :

1. Tim Ingold, Faire. Anthropologie, archéologie, art et architecture, Dehors, Bellevaux, 2017, p. 61

2. “Her footsteps were often resolved as a simple form of walking, but it was not quite dance”, in Tomorrow’s Sculpture, ROMA, Amsterdam, 2019, pp. 165-170,

©jcLett

©jcLett

Exhibition view, "Mnemosyne", Galerie des Ponchettes, Mamac, Nice,

photos François Fernandez

Exhibition view, "Mnemosyne", Galerie des Ponchettes, Mamac, Nice,

photos François Fernandez

Exhibition view, "Mnemosyne", Galerie des Ponchettes, Mamac, Nice,

photos François Fernandez

Exhibition view, "Futur, ancien fugitif", Palais de Tokyo, Paris,

photos : Aurélien Mole & Thomas Lannes

Exhibition view, "Futur, ancien fugitif", Palais de Tokyo, Paris,

photos : Aurélien Mole & Thomas Lannes

Exhibition view, "Mnemosyne", Galerie des Ponchettes, Mamac, Nice,

photos François Fernandez

Exhibition view, Le Cyclop, Milly-la-Forêt, mai 2017

Exhibition view, Le Cyclop, Milly-la-Forêt, mai 2017